In the years after 26/11, aspects of the police modernization program became visible in the city’s physical landscape. In the south of the city, new vehicles, weapons, and cameras were prominently displayed to inspire public confidence. For instance, a fleet of Mahindra Marksman jeeps were stationed at the Maharashtra state government headquarters Mantralaya and CST, also commonly known as Victoria Terminus or simply “VT.”

These vehicles were sometimes manned by quick response teams (QRTs) clothed in camouflage uniforms or small groups of police officers, some wearing protective vests and carrying pistols and submachine guns. Additional CCTV cameras had been installed across the south of the city, including at major railway stations.

The physical infrastructures at certain private and commercial sites in south Mumbai had also undergone significant change. The Taj and Oberoi hotels, both devastated during the attacks, had installed physical security perimeters, including planters, walls, and retractable anti-crash bollard systems to allow cars to pass in and out. These hotels were now equipped with baggage scanners and CCTV systems monitored by security control rooms inside. In the case of the Taj, these physical bollard systems were initially contracted out to the Israeli firm EL-GO Team, as I learned by speaking to the firm’s representatives in Tel Aviv.

Likewise, the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) had installed a yellow metal gate and a system of anti-ramming bollards purchased from the Israeli firm BG Ilanit Gates and Urban Elements Ltd. (BGI). And like CST and Mantralaya, at the Taj and the BSE there were also Marksman jeeps with police personnel on site standing or sitting on plastic chairs adjacent to the vehicles.

Major train stations like CST and Churchgate had installed metal detectors at their main entrances. Although the metal detectors were ostensibly installed to reassure commuters that their security was being taken seriously, their manifestations seemed to signal a tacit admission by the local state that securing the facility was impossible.

Unlike in other Indian cities like New Delhi, where public transport passengers are frisked and have their luggage scanned before entering the metro, I noticed that at CST and other Mumbai train stations passengers could pass through the scanners without being stopped, even if they had triggered the machine’s alarms. Many such stations and entrances lacked scanners altogether, and even in instances where a scanner was installed, passing through the scanners was entirely voluntary. Where scanners were present, there were often large gaps between them, which enabled commuters to walk around the machines if they chose.

Also read: Why Jews fought for separate statehood for Cochin

Some of the most common changes to Mumbai’s physical security infrastructure, however, had little to do with police modernization as such. One of the more noticeable changes was the increased physical fortification of strategic sites. These included the Bombay High Court and railway terminals like CST as well as police stations, like the Maharashtra police headquarters in Colaba a few blocks away from the Gateway of India and the Office of Mumbai’s Commissioner of Police opposite Crawford Market.

These fortifications took various forms, including improvised bunkers constructed out of sandbags and/or concrete blocks, typically manned by police constables armed with Indian Small Arms System (INSAS) rifles or vintage British Sterling submachine guns.

Even with the arrival of newly purchased weapons, the antique weapons remained in commission. As a former Maharashtra Home Ministry bureaucrat explained to me, “for the time being they [antique weapons] are being used” because police personnel “need weapons and until such time as we are able to give each a newer weapon, he has at least got something.” From speaking with such officials, I got the impression that these old weapons would not be phased out anytime soon. In other words, the arrival of new technologies supplemented, rather than replaced, preexisting police infrastructures.

During my travels across the city, I noticed other kinds of security perimeters set up at numerous sites to control movement, including the Gateway of India adjacent to the Taj. These barriers were constructed from low-tech steel roadblocks called nakabandi, which are prevalent across India. While the use of stop-and-search tactics using nakabandi have long been a staple of the Mumbai police, after 26/11 their usage became more widespread in response to public pressure to “do something” or “appear to be proactive.”

Thus, rather than signifying a shift from “civil” to “militarized” approaches to policing Mumbai, the introduction of “new” homeland security logics and technologies merged with the preexisting policing repertoires and physical infrastructures.

It is important to stress that well before 2008, Mumbai was one of the most heavily fortified cities in India with large swaths of its territory under the direct or indirect control of the Indian navy, army, and the Mumbai city and Maharashtra state police. Walking the city provided me with constant reminders that much of the city’s infrastructural fabric is “of war.”

The city’s deep connection to colonial and imperial military violence lives on in the naming of the city itself, for instance the area of south Mumbai known as “Fort,” named after Fort George, which was built by the East India Company. The city’s connection to ongoing forms of military violence was further made visible to me through other semiotic markers.

At Lion Gate, the entrance of the Naval Dockyard in south Mumbai, a sign warned would-be intruders in Hindi and English that the compound was a “HIGH SECURITY DEFENCE AREA” and that “TRESPASSERS MAY BE SHOT.”

Likewise, the rollout of the police modernization program also included various forms of security messaging. Some of this was clearly intended to boost public confidence, reassuring certain publics that they had a “right” to security and that surveillance was for their benefit.

A sign on a scanner at Churchgate Station read “Security Check is for the Benefit of the Passengers, Kindly Cooperate with the Railway Officials,” further noting underneath that “Being Safe Is Your Birth Right! [sic].” Along my journeys through the city, I also found signs echoing the DHS campaign “If You See Something, Say Something.” One sign instructed commuters that “ALERTNESS BEGINS WITH YOU!,” warning that “[t]he bag next to yours may not belong to an everyday commuter.”

Signs like these worked to boost security awareness and alertness as per programs aimed at interpellating new security subjects which were referenced in early issues of the Mumbai Protector [an English-language bimonthly police magazine launched in 2009]. Barriers outside of the BSE had similar messages, though struck a more conciliatory even apologetic tone. One read “thank you for your co-operation” and “sorry for the inconvenience.”

These forms of “banal” antiterrorism attempted to foment a sense of everyday unease but also facilitate the kinds of “dialogue with the people” that Mumbai Police Commissioner D. Sivanandan had called for in 2009. Much like the physical security measures above, however, these newer forms of messaging supplemented and augmented, rather than replaced, preexisting ones.

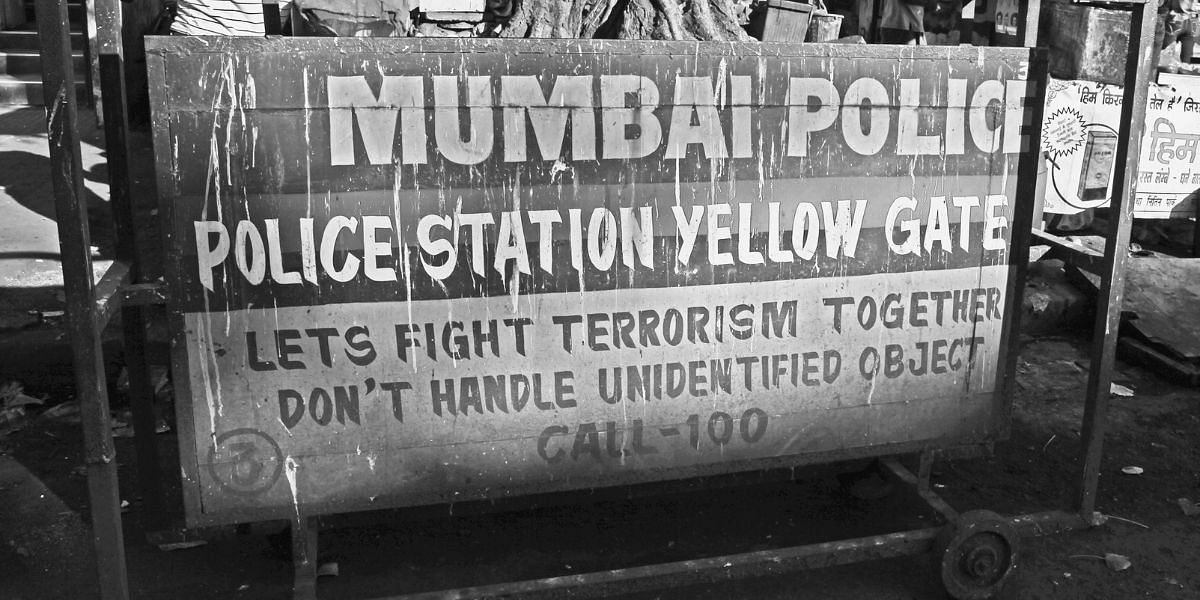

One nakabandi, which I encountered near Mumbai’s port area, warned passersby not to handle “unidentified object [sic],” instructing them to call the police to assist with the removal of such items (Figure 4.10). In contrast, a sign at CST gave instructions (in Hindi) to publics about how to handle such objects and notify police about them:

Your safety is in your hands. If you find unclaimed objects or vehicles near your area of residence, bring them to the notice of the nearest police station at once. Promptly keep sacks of sand around the unclaimed object to ensure that no one touches it—once blocked, take the residents away from it and inform the other residents of nearby areas—don’t crowd and cooperate with the police once informed.

At various suburban railway stations across the city, I encountered WANTED posters published by the Maharashtra ATS featuring pictures of four young Muslim men and a reward of Rs. 10 lakhs.

In Mumbai, police modernization thereby materialized in the form of hybrids or “mixtures” of different elements, grafting new weapons, surveillance cameras, vehicles, uniforms, and signs onto preexisting infrastructures while leaving the latter in place. The uneven implementation of metal detectors at CST illustrates how new technologies were not just layered onto preexisting infrastructure; such projects also materialized in uneven, patchy, and superficial ways.

The metal detectors were not the only example of this. By 2011, journalists reported that the majority of purchased speed boats were lying unused due to a lack of trained personnel and because funds were never allotted to purchase fuel for the new fleets.

This hybridized character of the police modernization program resonates with discussions of imperial bricolage characterized by a piecemeal and partial adoption of certain elements while leaving others behind. In so doing, these hybrids modified certain preexisting elements of Mumbai’s urban fabric and added certain new ones, yet hardly in the radically unprecedented or all-encompassing way that militarization tends to connote.

It is important to mention that not all the promised measures to secure the city came to fruition. For instance, early pledges by Maharashtra politicians to purchase helicopters never moved forward and efforts to modernize police infrastructure in Mumbai were plagued by ongoing controversies, corruption, and allegations of mismanagement.

This is an edited excerpt from Rhys Machold’s ‘After 26/11: India, Palestine/Israel’, where the academic notes and references have been removed. It has been excerpted with permission from Navayana.

This is an edited excerpt from Rhys Machold’s ‘After 26/11: India, Palestine/Israel’, where the academic notes and references have been removed. It has been excerpted with permission from Navayana.