Reports vary, but at least 500 and perhaps as many as 5,000 adivasi labourers and their families gathered in an open field outside the Ramgarh temple, next to a statue of the monkey god Hanuman, the divine protector of devotees, the guarantor of strength and victory.

The hullabol began as they often did, with music. Kanchuki led the crowd of exhausted laborers in protest songs. Hundreds of people chanted in unison: “No more exploitation; no more torture. We now unite to fight; we now unite to be free.”

Discussion of the new leases that had been granted to a handful of communities took top billing. The people of Bargarhi village explained how they forged connections with rock buyers, how they had negotiated their own prices for their rocks in the market, how they were making more money than they’d ever seen in their lives. Managing even a small rock quarry required an extraordinary amount of work, but the somewhat daunting freedom to make all of one’s own decisions was a burden they were willing to bear.

Also Read: Gandhi told Gujarat striking millworkers not to be angry at boss or gamble, gossip

Small groups chatted in hundreds of side conversations, committing to collectively save funds to establish their own quarries.

The organizers had presented a new plan of action. With an election approaching, the Kol people of Sonbarsa thought they could use the democratic process itself as a route to freedom. Someone explained the concept of a voting bloc. Kols accounted for nearly 40 percent of the population of Sonbarsa, so they presented a potentially formidable force in local elections. Ramphal and others decided that if they all cast their votes for the same candidate and did not allow their loyalties to be divided, the Kols could potentially select the next gram pradhan, or village head, perhaps even from among their own community. In Sonbarsa, the pradhan had always been a landlord. Ramphal remembers that the pradhan at the time was vindictive and often sent his associates to threaten the workers.

Because the pradhan lives among the people who elect him, he sees his constituents all the time; they know him by first name. Today, many people have their pradhan’s phone numbers saved on their cell phones and call the pradhan directly in times of crisis, whether it’s to report that a river has overtaken its banks or that a community member has died. It is a system that promises unusually direct democratic representation. Though many may fear such an engagement with a man so powerful (and we are talking largely about men here; despite the fact that a third of the pradhan seats are reserved for women, women often run as a proxy for their husbands), this hyper-visibility does in some ways keep local leaders in check. The pradhan is often elected because he has been anointed by the richest, most powerful people in the village, who then expect favors for having influenced the vote and for keeping the pradhan in power. The pradhan holds significant control over the distribution of government entitlements, especially before the institution of direct deposit banking accounts emerged in the last few years. A common complaint among the poorest villagers is that those resources are typically siphoned off by cronies of the pradhan. Thus, there is both significant reason to court a pradhan’s favor and significant risk if you lose it (or have no chance at securing it). With all these complicated political maneuverings dominating local governance, adivasis typically feel disenfranchised.

At the rally, the Kol people identified a possible candidate named Kashi, who had a modicum of education and had traveled outside of the village. Ramphal, Matiyaari, Choti, Sumara, and many of the Kols gathered in Ramgarh believed that they could trust Kashi to elevate their interests and lead their fight for rights and land through official channels.

Also Read: Time poverty is making Indian women lose more money than ever

Cheers and applause erupted after speeches. Sometimes the attendees broke into rousing protest songs. When the meeting came to a close, they felt a little bit taller, a little more equipped to face the next day. They didn’t want it all to end so soon, so many of them remained at the temple to enjoy some food and companionship. Kanchuki warned them that there could be reprisals from the landlords, but the workers, buoyed by the rally, told him he should return home to avoid any trouble, but they wanted to extend the joyful gathering as long as they could.

As the Kol men stayed behind to chat and clean up, the women headed in separate directions toward their homes. Suddenly, eight men on motorcycles blocked the women’s path. The women had seen the bikers lingering for most of the afternoon. They had loomed menacingly on the edge of the crowd, eating mangoes pulled from the trees that surround the temple and shouting epithets at anyone who would listen. As the women made their way toward the path home, they saw Virendra Pal attack a beedi seller and toss his tiny cigarettes into the dust.

The women tried to push past the bikers, but according to testimonies told to the police, reporters, and Amar at the time, the bikers began hitting the women, and even tried to run them over with their motorcycles. Virendra Pal shot a gun into the air. The men at Ramgarh heard the shots and came running, and fought with anything they could find at hand. There were as many as 50 Kols and only eight Patels. As news reporters would later announce, several of the Patel men were injured, and one died in the clash. It was Virendra Pal.

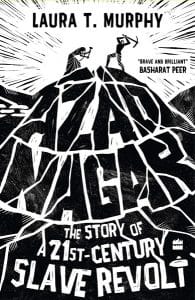

This excerpt from ‘Azad Nagar: The Story of a 21st-Century Slave Revolt’ by Laura T. Murphy has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.