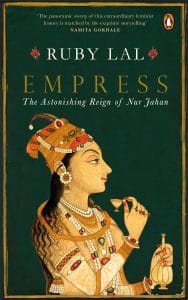

Ruby Lal’s new book chronicles the life of Nur Jahan, India’s most celebrated empress about whom shockingly little is known.

Little Prince Shuja, the fourth son of Shah Jahan and Arjumand, was a darling of the emperor. One day the boy was playing in a room of the Srinagar palace that had a low door, screened but not shut, facing Dal Lake. When Shuja ran toward the door to look out, he hurtled through it and fell fifteen feet. Luckily, he landed partly on a rug heaped below, and partly on the shoulders of the servant bent to spread it. Shuja’s head fell on the carpet and his feet on the shoulders of the man. “God, the Great and Glorious, came to his aid,” Jahangir wrote, “and the carpet and the farrash [carpet- spreader] became the means of saving his life.” When the farrash raced inside carrying the little prince, who was weak and not speaking, “my senses forsook me, and for a long time holding him in my affectionate embrace I was distracted with this favor from Allah.” Shuja recovered, but a dire prediction by Jotik Rai, the court astrologer, came true. A few months earlier, he’d announced “that one of the chief sitters in the harem of chastity would hasten to the hidden abode of non- existence.” Saliha Banu, one of Jahangir’s senior wives, passed away. The emperor didn’t say in his journal whether she was part of the royal group in Kashmir or back in Agra, but he noted that “the grief for this heartrending event laid a heavy load on my mind”—more emotion than he recorded at the death of Jagat Gosain. The emperor expressed his sorrow sincerely but briefly. His polygamous household was by this time a somewhat distanced, symbolic presence. Nur was his daily companion.

However pleasing Nur may have found the sojourn in Kashmir, she had a serious matter to deal with, the question that had long weighed on her mind: Which of the Mughal princes should marry her daughter, Ladli Begum? Shah Jahan, Jahangir’s favorite and the presumed successor to the Mughal throne, was politically perceptive, accomplished, and fiercely ambitious. Of the four princes, he was most likely to succeed his father. But he was already married to Nur’s niece Arjumand and two other women. Nur would certainly have noticed that since his marriage with Arjumand, Shah Jahan had fathered all but one of his children with her; she was his favorite. Ladli would become a subordinate wife.

Furthermore, it had become increasingly clear to Nur that if he were to become emperor, the ambitious Shah Jahan, already looking forward impatiently to claiming his patrimony, might not welcome Nur as any sort of counterpower. With him on the throne, she might have no imperial future at all. Nur’s musing on that strong possibility may have accounted for the cooling of her formerly cordial relationship with Shah Jahan. She eventually reached the conclusion, says one modern Mughal scholar, that Shah Jahan “would undermine her power in a post- Jahangir dispensation.”27 She needed to think carefully about choosing a royal husband for Ladli who might become the next emperor instead of Shah Jahan, someone who would preserve something of his mother- in-law’s power.

In early October 1620, the imperial banners turned toward Lahore, where the party would stop on the way back to Agra. The return march began from outside the Kashmiri city of Pampur, where as far as the eye could see, there stretched a natural carpet of saffron. Along the way to Lahore, the cavalcade stopped at some of the same spots where they had paused on the journey to Kashmir. As before, the core camp halted at passes that were exceptionally difficult and rough to cross. Jahangir had difficulty breathing.

In early November, the royal party reached Lahore, where they got some good news. Shah Jahan had taken a break from the Deccan campaign to head north and score a victory at Kangra, in the Himalayan foothills; he and his men had taken the fort, subdued a raja fighting Mughal rule, and returned to the Deccan.

In early December, messengers brought news far less cheering. In the Deccan, enemy assailants were destroying fields and pasturelands. Mughal forces had fought a heroic battle, but exhausted and short of resources, they retreated. In early December, Shah Jahan traveled from the Deccan to Lahore for a brief visit, probably a strategy session, with Jahangir, Nur, and their inner circle.

Jahangir’s shortness of breath continued to worsen, making the question of Mughal succession seem increasingly urgent. No documentary evidence suggests that Nur ever broached the subject of Ladli’s marriage with either Shah Jahan or Parvez, the alcoholic son on the margins of Mughal political life. Khusraw, the partially blinded prince, wasn’t a good prospect either, although the Italian traveler Della Valle, who visited India three years before Jahangir’s death, but never met him or Nur, assumed that Khusraw would succeed his father to the throne. In order to “establish herself well,” Della Valle wrote in his book The Travels of Pietro Della Valle in India, Nur Jahan “frequently offer’d her Daughter [to Khusraw] . . . but he, either for that he had another Wife he lov’d sufficiently and would not wrong her, or because he scorn’d Nurmahal’s Daughter, would never consent . . .” The fact that Khusraw was in the Deccan during this period suggests that Della Valle was writing from hearsay. Thomas Roe, the British ambassador, speculated similarly about a supposed proposal of Ladli’s marriage to Khusraw.

Ultimately, Nur chose Jahangir’s youngest son, Shahryar, as her daughter’s husband and the potential preserver of her power. He was a long shot to succeed— Jahangir seemed set on Shah Jahan as his heir— but a possibility. Shahryar was known for his good looks, patience, and restraint— and for being easily manipulated.

Mughal princes could be groomed as successors. If the right steps were taken and a prince had enough support, if he skillfully accomplished military and political assignments well, he could become a contender for the throne. Nur decided she would take a chance and campaign for Shahryar as successor to Jahangir, knowing full well that it would be hard to keep Shah Jahan from the throne.

Just before the royal party started the journey from Lahore to Agra, the emperor formally approached Ghiyas. “I asked for the hand of I’timaduddawla’s grand- daughter in marriage to my son Shahryar,” Jahangir wrote, “and a lac of rupees in cash and goods was sent as a sachiq [a gift sent from the prospective bridegroom’s house to the bride’s]. Most of the great amirs and important courtiers accompanied the sachiq to I’timaduddawla’s quarters, where a large celebration of utmost elaborateness was held. It is hoped the marriage will be blessed.” Also attending the celebration at Ghiyas’s impressive Lahore residence of the diwan of Punjab— one of Ghiyas’s many titles— were Nur, a coterie of royal women, and the newly engaged pair themselves, Ladli and Shahryar.

Once Ladli was engaged to Shahryar, the rift between Nur and Shah Jahan deepened.30 Shah Jahan knew what Ladli’s marriage could mean. He was leaving for the Deccan, the emperor was weakening rapidly— and Empress Nur was at the center of the imperium, now closely tied to another prince who could easily become a contender for the throne. Before Shah Jahan’s first expedition to the Deccan, his father, Nur, and others had assured him that his interests could be protected during his absence. As the prince prepared to depart once again for the Deccan this time, his youngest half- brother Shahryar, Nur’s new protégé, occupied his mind. On December 16, 1620, Shah Jahan left again for the war in the south, adorned with a robe of honor, a jeweled sword on his waist, mounted on an elephant that Nur had given him— a public acknowledgment, however reluctant, of her power. The royal retinue headed for Agra that same day.

This excerpt is from the book ‘Empress: The Astonishing Reign of Nur Jahan’ by Ruby Lal. It was published by Penguin Random House in 2018.

This excerpt is from the book ‘Empress: The Astonishing Reign of Nur Jahan’ by Ruby Lal. It was published by Penguin Random House in 2018.

Shah Shuja was not the fourth son of Shah Jahan but his second son after Dara Shukoh … his fourth son was Murad Baksh . The author does not even know history properly but has written a book .