Lakshmi stares out at the crowd as she settles herself on stage. She’s confronted by a sea of people to whom she is unknown. She must win them over and make them look past the fact that she is a woman, and furthermore, a South Indian woman. She must convince them that although Hindustani music is not in her heritage, it is in her heart, and although it was not her first muse, it is now her only one.

She closes her eyes and focuses on the three years of relentless practice and preparation that have brought her to this day. She draws comfort and confidence from her guruji seated next to her, and the traditions and techniques of the Patiala Gharana that have made their way across time and space to her. Khan Sahib had determined the perfect combination of khayals and thumris that would showcase her range and dexterity and she has practised them devotedly, all in anticipation of this moment.

When Lakshmi arrived in Calcutta for the Entally Festival, although the gravity of her debut was not lost on her, she was smitten by the festival’s celebratory atmosphere.

Also read: Coimbatore Thayi, the Carnatic singer who struck a chord in Paris but is unknown in India

‘Oh, how they used to decorate the stage … like a pooja pandal,’ she gushed to me, recalling the event. Her guru, Ustad Abdul Rehman Khan, had accompanied his star pupil for her debut. ‘My teacher had come with me because that was my first conference and he said, “I’ll be there with the harmonium so that you feel confident.”’

On stage, Khan Sahib’s hands began to unspool the notes of the first raga on the keys of the harmonium. Lakshmi began to sing, tentatively at first and then with greater ease. Her voice plumbed and soared in search of the emotional and textural landscapes unique to Raga Malkauns. Her guruji kept encouraging her all the while.

‘I was very nervous, of course, but my ustad made me feel good by playing. He would say, “Wah wah”, and all that so I felt very good. I said, “My God, at least I’ve not blundered,”’ Lakshmi told me. The second gauge of her performance came from the audience. ‘They would say, “Waah, waah, waah” – I never did gimmicks – but when I speeded it up or something, they would clap.’ She was buoyed by the audience’s approval and appreciation because she knew that this ‘… kind of audience … they’re terribly fond of classical music.’

However, the ultimate validation of her performance came from the organizers of the festival. ‘Many people said they want to have another sitting [performance] … so they gave me an early morning slot.’ Lakshmi was thrilled to be invited to sing again at four o’clock the next morning. It was not unusual for music festivals to be twenty-four-hour events, allowing them to take advantage of every hour by featuring more artists.

This second sitting was not only an endorsement of her skill but an opportunity to showcase more of her repertoire, for she would have to perform ragas suited to the early hours of the morning. So, once again Lakshmi took to the stage, this time after a night full of performances, and sang the lilting Raga Lalit and the haunting Raga Bhairavi, mesmerizing the crowd. The success of her debut performance at Entally lifted a burden off Lakshmi’s shoulders, one that she’d been carrying for three years. Although a triumphant debut doesn’t necessarily guarantee a successful career as an artist, it is a pivotal first step that holds great professional and personal significance.

‘Getting a name in there was terrific for me. It just … gave me courage.’ Years later, looking back at the launch of her career as a Hindustani singer, Lakshmi said with a measure of awe, ‘From that day, I never looked back. By God’s grace I came back to Bombay and I got opportunities to sing there.’

Also read: Gauhar Jaan, India’s first record artist, took Rs 3,000 a session & threw parties for her cat

However, just as Lakshmi was ready to embark on her nascent career with the support of her guruji, a strange rift emerged between them. ‘After the Calcutta conference there were – I don’t want to give any names – Maharashtrian ladies, quite a few. They were all learning from him … They started telling him things. “Oh, you know, she’s gone above you and she’s made you a harmonium player, because you went and played there.” And all sorts of chuglis went on … so he said, “What is this? I won’t teach you anymore.” I said, “What can I say, I never think of you in this way. I think you are the greatest musician and my guru.” But he didn’t listen.’

Her dream debut at Entally was shattered by the ‘gossip’ and ‘jealousies’ of Khan Sahib’s amateur students, leaving Lakshmi wondering if her career as a Hindustani singer was over just as it was beginning. Rajendra, who had supported Lakshmi all this while by running the household and looking after the schooling of young Kumar and Viji, suggested that she return to her roots by pursuing Carnatic music. Given Lakshmi’s heritage, it would be less challenging for her to be accepted as a Carnatic vocalist.

At the time, like Hindustani music, Carnatic music was also gaining backbiting popularity because of the advent of radio and recording. But Lakshmi’s interest in Hindustani music was by now unshakable and she was not ready to give up on her dream. In the meantime, she continued to seek out and accept opportunities to sing in Bombay and it was through her continued perseverance that she found her next guruji, B.R. Deodhar. Deodhar was born in 1901 in Maharashtra and had been a pupil of Vishnu Digambar Paluskar, who was a key scholar and codifier of Hindustani music across its various branches and gharanas. Paluskar also established the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya, one of the earliest open schools for Hindustani music, as a formal alternative to the gharana system.

Also read: Salem Godavari, Carnatic vocalist who fought superstitions to record erotic compositions

Meanwhile, Lakshmi kept performing locally in Bombay and although she felt like she was at a professional standstill, she continued building connections to other Hindustani artists and proponents. ‘So I was in a soup. I had hardly learned for three years from Ustad Abdul Rehman Khan… B.R. Deodhar used to have a festival every year in Bombay for Gandharva Mahavidyalaya, for his guru. So, he put me there to sing and it was a big success. Then I told him that this is what has happened, and I don’t know what to do. So, he thought it over and he said, “Well, Lakshmi, you’ve got a style … Patiala style. You’ve got it in you. I have gathered and collected many, many bandishes – bandishes means compositions – from different gharanas. I’ve got quite a few Patiala bandishes. If you want, you can come to me and I can coach you on those. And then you can also do your BA Sangeet Visharad degree.” It [the degree] was equivalent to a bachelor’s in music.’ Lakshmi was thrilled.

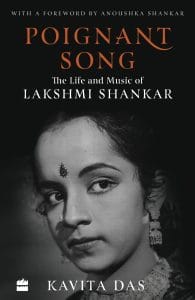

This excerpt from Poignant Song: The Life and Music of Lakshmi Shankar has been published with permission from Harper Collins India.

This excerpt from Poignant Song: The Life and Music of Lakshmi Shankar has been published with permission from Harper Collins India.