Even though it seems unlikely that they went away in the intervening years— which included two centuries of the Moghul dynasty, from 1526—bovine issues subsequently became noteworthy again in recorded histories in the late nineteenth century. This interest might, in part, have been because Hindu perceptions of the cow were at such variance with those of the beef-eating colonial officials who recorded them, coupled with the not unjustified fear that resistance to pro-cow sentiment might damage the British Raj’s capacity to govern. But the resurgence of cow protectionism also had much to do with the flourishing of Hindu reform movements, such as the Arya Samaj, founded in 1875 by Swami Dayananda Saraswati. These movements, in turn, blossomed through the improved communication systems of the time, including the railways, the telegraph, and the press. In short, we can see the confluence of divergent contributory factors to create an “ecological niche” (Hacking 1988, 2): an environment in which it was conducive for cow protectionism to become embedded in everyday life. The cow, in this period, was reconstituted as a key symbol in the growth of Indian nationalism—and cattle protection a cause around which, the British feared, Hindus could unite—against a beef-eating British (Gould 2004) and minority Muslim population (Robb 1986, 292).

The Arya Samaj, which called for a return to the Vedic principles that it argued were being ignored by a corrupt priesthood, also popularized cow protection, a cause taken up by a variety of organizations. “The original Gaurakshini Sabha founded by Dayananda,” historian Ian Copland notes, “focused initially on propaganda, disseminated via local branches and itinerant preachers called gauswamis, then shifted to direct action, which included operations to liberate cattle intended for slaughter and abusing and roughing up Muslim ‘cow killers’” (2014, 421n58). The latter activity—which resonates with stories I collected from beef sellers in 2017—helped spark, as Copland also discusses, a series of “cow riots” in northern India during the 1890s. One of these was the Basantpur riot in rural Bihar in 1893, provoked by a Muslim-led procession of cattle intended for slaughter through the Saran District. On the broader impact of cow protection activities, historian Anand Yang noted, “Although initially at least the message of cow protection was phrased in eclectic terms, increasingly the issue was seen as defining people’s relationships and activities. Under the Sabha’s influence, many everyday routines took on a different order. In many villages, Muslims were refused access to wells” (Yang 1980, 588).

Comparable disorders were reported in Delhi in 1886, in response to the sacrifice of 450 cattle by Muslims during Eid al-Adha, and elsewhere in India over the next decade, as orthodoxy over the cow seemed to spread eastward, from the Punjab and into Bengal.15 The issue remained a live one into the next century, with, for example, the increased influence of the Cow Preservation League in Calcutta during the 1920s (Copland 2014, 241). The league, along with the cow protection movement more generally, was responsible for a growing number of pinjarapoles and goshalas (cow protection sanctuaries and societies) that began to spring up across India. What is also noticeable about Dayananda’s approach was its emphasis on the economic, or practical, value of the cow. Although the separation of the economic and the religious into discrete realms has rightly been identified as a facet of Western categorizations rather than a universal one, Dayananda was likely aware of this in making the case for cow protection in the terms that he did (Adcock 2010, 304). Given the colonial government’s reluctance to interfere in religious matters, framing objections to cattle slaughter in utilitarian terms—that they did more good alive than they did dead—made sense. But for the Arya Samaj, these benefits were not only secular. They drew no distinction between the “economic” and other reasons for protecting cows (Adcock 2010; 2018).

In the context of cow protection, it is essential to consider the broader implications of animal cruelty and how it intersects with cultural practices and legal frameworks in India.

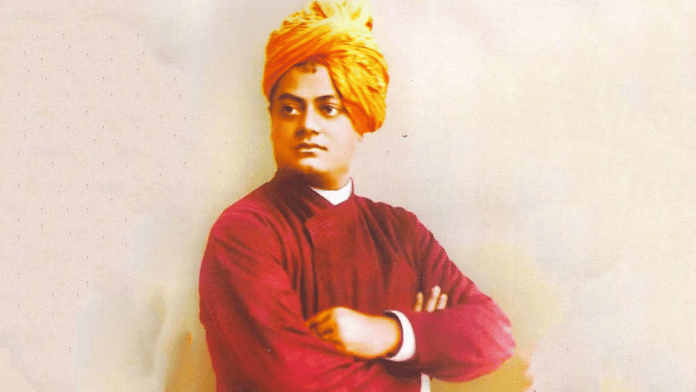

Mahatma Gandhi drew on some of the same arguments. But for him, love of the cow was also a facet of his broader challenge to colonial gastropolitics, which included disrupting associations of meat eating with masculinity and superiority and vegetarianism with effeminacy (Premanand Mishra 2015, 81). Although in his youth Gandhi had been inspired by Swami Vivekananda’s oft-invoked prescription of “beef, biceps and Bhagavadgita” (Roy

2002, 66) as an antidote to colonial accusations of Indian effeminacy, he later argued that colonial subjugation would better be overcome through valuing vegetarianism as a cultural practice (Premanand Mishra 2015, 85). As such, despite condemning violence against Muslims who consumed beef, Gandhi became firm in his support of cow protection, describing it at one point as the “central fact of Hinduism” (1999, 374). In the same passage, he went on: “Cow protection to me is one of the most wonderful phenomena in human evolution. . . . Cow protection is the gift of Hinduism to the world” (374). Although he was also critical in his writings of the way in which cows were treated by his fellow Hindus, some have argued that it was through Gandhi’s pronouncements on the matter that the cow’s status as holy finally became implanted in the minds of the Hindu population (Korom 2000, 188–89). Anthropologist Frank Korom speculated that “perhaps it was the rupture created by colonial rule that facilitated the need to ‘invent’ the cow as a Vedic object of veneration” (2000, 189). Certainly, the BJP leader Narendra Modi made regular (but selective) references to Gandhi’s rejection of meat in his own promotion of vegetarianism and, while chief minister of Gujarat in the early 2000s, in clamping down on Muslim-owned slaughterhouses in Ahmedabad (Ghassem-Fachandi 2012, 154–56).

Whatever the causes—and it seems likely that they were multiple—it is clear that the cow veneration of the late nineteenth century reflected a recasting of a Vedic past to deal with present-day issues and the problem of British rule, and in particular to subvert their logic that superiority was rooted in meat eating. This manipulation of bovine history continued into the postindependence period.

This excerpt from ‘Sacred Cows & Chicken Manchurian’ by James Staples has been published with permission from Harper Collins.

This excerpt from ‘Sacred Cows & Chicken Manchurian’ by James Staples has been published with permission from Harper Collins.