After the war began, Britain started looking at the whole Zionist movement from a different perspective. Weizmann saw the emerging geopolitical situation in the Ottoman Empire as an opportunity to advance the Zionist cause. In Britain, he met members of the powerful Rothschild family and sought their help.

James de Rothschild, son of Baron Edmond de Rothschild, told Weizmann in a meeting in November 1914 that Zionists should demand not just colonization of Palestine through settlements but the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine. He argued that ‘the formation of a strong Jewish community in Palestine would be considered as a strong political asset’ by London. In the same month, the British Cabinet discussed Palestine for the first time, weeks after Britain entered the war.

In the meeting, David Lloyd George, then chancellor of the exchequer who would soon become Prime Minister, told his colleague Herbert Samuel, a secular Jew who was sympathetic towards Zionism, that he saw the ‘ultimate destiny of Palestine in becoming a Jewish state’.

As the war was unfolding, Weizmann would later write: ‘an opportunity offered itself to discuss the Jewish problems with Mr C.P. Scott (editor of the Manchester Guardian)’. Scott, an influential figure in Manchester’s liberal circles who enjoyed a close relationship with Lloyd George and Herbert Samuel, was sympathetic towards the Jewish community. He introduced Weizmann to Lloyd George, who asked the Zionist leader to meet Herbert Samuel.

On 10 December 1914, Samuel received Weizmann at his office. Weizmann’s key demand was support for settlements and building institutions in Palestine. A state cannot be created by decree, ‘but by the forces of a people and in the course of generations’, he said. But Samuel was more ambitious. He told Weizmann his demands were too modest. ‘Big things will have to be done in Palestine.’

When Weizmann asked the British leader what his ambitious plans were, he said he would rather keep them ‘liquid’, but added that ‘Jews would have to build railways, harbours, a university, a network of schools, etc’.

Also read: Does the old international order get the brave new India? What Dhruva Jaishankar says

Within three months, Samuel circulated a memorandum titled ‘The Future of Palestine’ in the British Cabinet. Samuel, a long-time supporter of the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine, however, believed that the time had not yet come for creating an independent state.

Instead, he suggested the British Empire annexe Palestine once the war was over, and ‘help the gradual growth of a considerable Jewish community, under British suzerainty, in Palestine’. Samuel argued that as a ‘civilizer of the backward countries’, England would be fulfilling ‘yet another part of her historic part’.

‘Under the Turks, Palestine has been blighted. For hundreds of years, she has produced neither men nor things useful to the world,’ he wrote in the memorandum. Samuel further argued that annexation of Palestine would raise the prestige of the British Empire, help it in its war efforts, and ‘win for England the lasting gratitude of the Jews throughout the world’, including the 2 million Jews who resided in the United States. This was the first time a British cabinet minister put a plan in favour of the Zionist cause in the official records.

Discussions, both at the Cabinet level and between the government and the Zionists, continued. Weizmann, who by that time had become the face of the Zionist movement in Britain, was appointed as a scientific adviser in the Ministry of Munitions, which was headed by Lloyd George.

In the midst of war, when Britain was under pressure for the mass production of acetone, Weizmann came up with a solution. He found a way to produce acetone by a fermentation process in a laboratory, and with help from the government, industrial scale production of acetone started. This enhanced Weizmann’s reputation among the political establishment in London. Llyod George reminisces in his memoir establishment about a conversation he had with Weizmann:

‘You have rendered great service to the State, and I should like to ask the Prime Minister to recommend you to His Majesty for some honour.’

‘There is nothing I want for myself.’

‘But is there nothing we can do as a recognition of your valuable assistance to the country?’ I asked.

‘Yes, I would like you to do something for my people,’ he said.

‘He then explained his aspirations as to the repatriation of the Jews to the sacred land they had made famous. That was the fount and origin of the famous declaration about the National Home for Jews in Palestine,’ writes Llyod George, referring to the Balfour Declaration.

Llyod George’s account overlooks the complex geopolitical dynamics that were at play in the early twentieth century. True, Weizmann’s support for the war effort, in his individual capacity, and the respect he commanded in Britain’s establishment provided him access to the top echelons of the British government. But Britain was also mindful of its own interests.

In 1915–16, the war was raging on multiple fronts with no major breakthrough for either side. The Allied Powers were under enormous pressure. The United States had not joined the war yet, and Russia was going through a period of revolutionary instability with the rise of the Mensheviks and the Bolsheviks. British leaders calculated that if they supported the Zionists, they could win, as Samuel Herbert wrote in his memorandum, the support of the Jewry who could use their influence in bringing the United States into the war and persuade Russia to stay in the war.

Lloyd George and Arthur Balfour had also supported the idea of dividing the Ottoman lands once the war was over. So, they thought that having a sizeable Jewish population in Palestine would help Britain’s interests in West Asia. Britain could also claim moral leadership by offering a solution to the Jewish question. This line of thinking emerged stronger after Lloyd George became Prime Minister and Arthur Balfour his foreign secretary in December 1916.

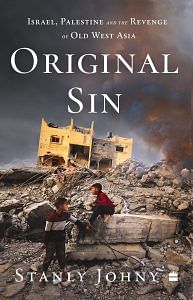

This excerpt from ‘Original Sin: Israel, Palestine, and the Revenge of Old West Asia’ by Stanly Johny has been published with permission from HarperCollins Publishers India.

This excerpt from ‘Original Sin: Israel, Palestine, and the Revenge of Old West Asia’ by Stanly Johny has been published with permission from HarperCollins Publishers India.

The Jewish people are an example to the rest of humanity. Their industrious nature, enterprising ability and extraordinary intelligence has meant that they have dominated global commerce and every single branch of human endeavour.

The Palestinians would do well to learn from them and try to emulate them.