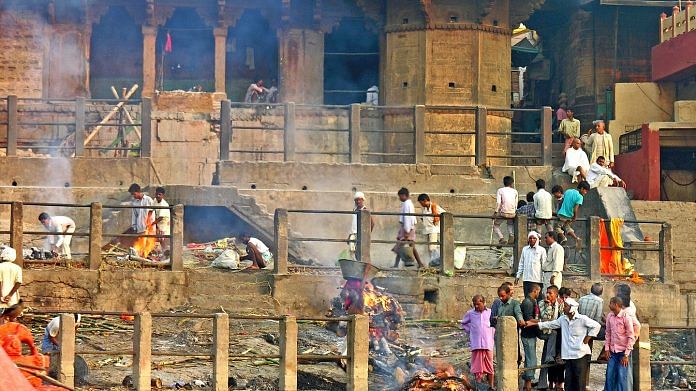

The modern-day crematorium at Harishchandra Ghat, which had been neglected for over three decades by Hindus who visited Varanasi to cremate their dead by using wood and fire, was in 2021, suddenly in dire demand. But it could not cope with the alarming number of infected corpses that arrived at its doorstep every day.

Banaras’s sole electric crematorium was inaugurated in 1989. For several decades prior, particularly in the 1970s and early 1980s, the Doms had fiercely stalled its construction. They feared that the modern-day crematorium’s services would blight their only source of survival. Devout locals backed the Doms’ fight. At the forefront of the resistance was Dom Raja Kailash Chandra Chaudhary, who wielded symbolic clout and was vehement in protecting his family’s claim over the ‘burning ghats’.

He declared that the presence of the electric crematorium in the holy city would tamper with the faith of the Hindu masses. For many years, due to Kailash Chaudhary’s stance, the electric crematorium project was delayed. After his death in 1985, however, the government speedily launched the Ganga Action Plan, which was geared towards mitigating the pollution in the river, and under this plan the electric crematorium at Harishchandra Ghat was successfully set up.

The electric crematorium was positioned as a solution not only to keep the Ganges clean, but also to diminish the degree of air pollution caused by open-air pyres and to extensively reduce the usage of wood. It was easy on the pocket—in 2012, the electric crematorium cremated bodies at the subsidized rate of Rs 500 per corpse—while the cost of traditional cremation was upwards of Rs 4,000. The modern crematorium was also time-conscious: it took forty-five minutes to do the work, while the waiting period for a body to cremate fully with wood and fire was over three hours. In a nutshell: the new crematorium was cheaper, quicker, safer and environmentally friendly.

Despite its many positives, the electric crematorium failed to run successfully. Many believed that a non-wooden cremation, one that was not held at the sacred river’s edge, would not provide absolute salvation. And so, corpses continued to be laid out and cremated on traditional pyres.

For years, then, the electric crematorium was only fired up when unclaimed corpses were found on the streets by the police or when the poor could not afford to buy the expensive samagri and wood. They would have their loved ones cremated at the electric crematorium out of desperation, not choice. The first time I visited the electric crematorium in 2015, I learnt that as few as three to five bodies were cremated on a daily basis there. To encourage more people to use the electric crematorium, the service was made free. However, that did not do much to boost its popularity either.

I also learnt that to pacify the Doms, the crematorium authorities agreed to hand over the ashes obtained after cremating each corpse to the community, allowing the Doms to use the ashes for ‘dhulna’.

In 2015, in the middle of winter, Santosh Chaudhary wasn’t expecting visitors. At the decrepit electric crematorium, Santosh worked as its chief operator. The crematorium was within a building that stood at a height, next to the traditional cremation ground at Harishchandra Ghat.

On the day of our meeting, Santosh, a wiry man in his late twenties, was standing in front of a glassless window, in a cotton shirt and a blue sweater that hung loosely over his shoulders. His hands were clasped at the back as he solemnly looked ‘out of it’. The window framed the regal bluish-grey river, flowing and alive—a stark contrast to the eerie stillness of the crematorium. Natural light lit the interiors. The room was sparse, inhabited by twin giant furnaces that occupied a large portion of the space. One of the Dom children once described the furnaces as ‘flesh-eating’ machines that swallowed bodies wholly. The air in the electric crematorium was still and quiet, occasionally disturbed by the cooing of pigeons: a stray flutter here, a one-legged perch there.

Santosh told me that when the corpses were delivered, it was his job to keep a diligent record. In a single-lined notebook, he wrote, in Hindi, the deceased’s name, age, city’s name or village, and so on.

‘As an operator, I ensure that I maintain the file and see that the documentation is fine. I have to make sure that all the documents are there, and at the end, I open the gate [of the electric chamber] while another Dom assists me,’ he explained. The corpses were laid on a lift table—an iron tongue that resembled a gurney—and the bodies were then wheeled into the mouth of the cremation pit. ‘We get at most five bodies a day,’ Santosh informed me. ‘Not more than that.’

Santosh, who belongs to the Dom community, holds a Master’s in English. Through a special quota for Scheduled Castes/ Scheduled Tribes, he studied at the Banaras Hindu University (BHU), considered to be one of the finest institutions in the city. After graduation, he worked as a tuition teacher for a while, before securing a full-time job at the crematorium. Despite his education, the only job Santosh managed to acquire involved dealing with corpses. ‘For now, this job is good, but I’d like to do much more,’ he said in an aspirational tone. ‘I’m currently preparing for my Master’s in Political Science. I want to become a professor at a government college.’

Santosh comes from a family of maaliks. While his four brothers, who live in the Dom colony near Harishchandra Ghat, had studied, they had decided to carry the family tradition forward as maaliks. Santosh had dreamed of becoming much more, he told me. As the only one in his family who desired a profession that strayed from tradition, he studied and received a Master’s degree.

‘My brothers sometimes make five thousand rupees a day, while I make that much in a month,’ he said dryly. It was a price he paid, he said, to do something different. Yet, Santosh, who felt that his presence at the crematorium was vital, said that unlike at the burning ghats, where a day’s earning was dependent on the number of corpses that arrived there, working at the electric crematorium offered a steady income and a cooler, less frantic surrounding.

Could his job, however, be given to anyone else who was perhaps as educated as him but came from a different caste, I asked.

The question seemed to offend him. ‘You see,’ he said, challengingly, ‘we might be able to work the camera that you are holding once we learn how to use it. But no upper caste man or woman, including you, would ever want to touch a dead body, let alone do our job.’

Santosh narrowed his eyes. ‘This is my birth right!’ he continued, enunciating the word ‘birth’ with discernible pride. ‘Only I and those in my community can burn corpses. We are the Doms.’ His voice resounded through the crematorium.

It is the caste system, however, that continues to ensure that only the Doms handle the dead. No ‘upper-caste’ Hindu will be willing to perform the task of burning corpses, even if the said work has been ‘glorified’ for centuries as the only way of ‘providing moksha’.

Santosh took a deep breath and assessed the vacant crematorium and its morbid calmness. As its chief operator, he wished more corpses were cremated there so that the crematorium’s purpose was fulfilled. ‘If one body burns here, at least one tree is saved,’ he said.

This excerpt from Radhika Iyengar’s ‘Fire on the Ganges: Life among the Dead in Banaras’ has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.

This excerpt from Radhika Iyengar’s ‘Fire on the Ganges: Life among the Dead in Banaras’ has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.