I became a professional cricketer at the start of 2011, and that’s a summer I’ll never forget. One day I was finishing school and getting ready for uni, the next I was debuting in first-grade cricket, then debuting in the New South Wales side, then in Big Bash cricket. It all happened in a flash, and all before I could legally have a beer.

In May 2011 I celebrated my eighteenth birthday, and then I was looking forward to more cricket, hopefully for New South Wales. A month later I was shocked to hear that Cricket Australia were offering me a contract. In November 2011 I was in South Africa, getting my baggy green from Ricky Ponting after some good form in T20 and One Day

games, and after Ryan Harris suffered an injury.

Getting that first Test cap was like being in a dream. I’d been a skinny grommet slashing around with my brothers in the backyard – and then, all of a sudden, I was playing for Australia in a Test match. My debut in Johannesburg was a dream also: I got six wickets in the second innings, scored the winning runs and was named Player of the Match.

Alongside that dream, however, was a thin vein of cold reality. As I bowled in the first innings, a pain developed in my foot. It got worse with each day’s play and each spell of bowling. After the match I had a searing pain in my heel, but I thought it was caused by bruising that would improve with ice and time. This wasn’t the case. I was diagnosed with a rupture of the fat pad in my heel and also with a bone stress injury.

That was the beginning of a very tough period in which I took one step forward and two steps back for years. After being sidelined for the entire 2011/12 home summer, I managed to return to cricket – for Australia’s under-nineteens side – in April 2012. I then played for Australia in the T20 World Cup and for the Sydney Sixers in the T20 Champions League. Before I could get back in the Test side, however, I broke down again. I had some scans to try to locate the cause of the pain I was experiencing in my back; they revealed I had stress fractures. I’d be out of cricket for at least the Australian summer.

It was a time of immense frustration. I knew I could play against the best players around, and I desperately wanted to keep testing my skills against theirs, but every time I got a few games together or a good run of training, some injury or diagnosis dragged me back to square one.

Advice came thick and fast. In 2012, I started to try to remodel my bowling action. Some coaches had suggested that this might limit the likelihood of future injuries and get me back onto the pitch. I was often told to bowl through it, which I tried to do, but I did so with pain, unable to even bend over to tie my shoelaces.

Also read: A question about coaching institutes stumped a Kashmiri IAS aspirant

I ended up not liking my cricket that much. I’m not a technician as a cricketer: I’m a competitor. I’d never been much of a nets bowler at the best of times, and the mundanity of bowling in the nets, not knowing when I was going to play again, was not my idea of fun. It was like I was learning to walk again from scratch. I did it, though, bowling and bowling and bowling, trying to find a new action that would work. But as I did that, it felt like I was just getting worse; like I was losing what I thought had made me a good bowler. I felt like I was losing the bounce and accuracy – and ten or so kilometres of pace – that were my strengths.

I became pretty dispirited. I was still young and had a lot of cricket ahead of me if I stayed available, but I wondered if I’d always struggle with injuries, spending my career doing the part of cricket that I don’t enjoy that much – bowling in the nets and working in the weights room – without consistently enjoying the part of the game that I love: competition.

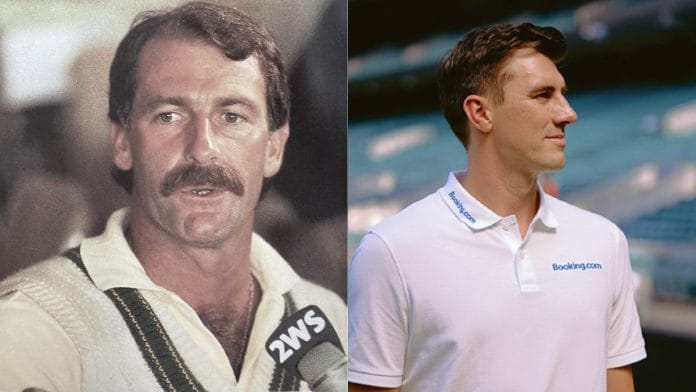

In any sport, the best ability is availability, and I wondered whether I’d ever show the consistency and availability required to be picked consistently for Australia. Then my manager, Neil Maxwell, made a suggestion to me. He said I should go to Perth and do some sessions with Dennis, who Maxxy said had helped Brett Lee immensely.

Since retiring from professional cricket, Dennis had become a legendary coach, mostly due to coaching that he’d done in India for an organisation called the MRF Pace Foundation. This foundation had been established in 1987 by Ravi Mammen, the managing director of a company called the Madras Rubber Factory and also a massive cricket fan. Mammen was a wealthy businessman who wanted to be a benefactor for Indian cricket, believing the best way he could do that was to develop fast bowlers for a national side that was usually weighted towards spin bowling. To that end he wanted Dennis’s help. Dennis became the director of the MRF Pace Foundation, drumming into the Indian players a dedication to fitness, core strength and diet, as well as tactics and bowling fundamentals.

Multiple generations of great fast bowlers went through the MRF Pace Foundation, and not only Indian players. Brett Lee’s time with Dennis was at the foundation, and Glenn McGrath spent time training there also. By the time I started working with Dennis, he’d only just retired as the Foundation’s director, having been replaced by McGrath. Dennis taught me a hell of a lot that was accessible and most importantly enduring, and I give him a lot of credit for the durability I’ve ended up having in my career.

In 2012, Dennis took me all the way back to the basics. We looked at the dynamics of my bowling, studying my run-up and then my approach, my action, my landing and follow-through. Dennis didn’t want to be radical and tear the book up and start again. I already had an action and a successful one, Dennis could tell that, so he just wanted to see what changes could be applied. We tinkered and investigated whether there was any extraneous movement and, if so, where it started. Could it be eradicated or counterbalanced? Where was energy gathered and expended? How could I reduce some of the twisting, while still holding on to my strengths?

I guess this approach wasn’t a million miles from the other coaching I was getting, but I enjoyed it more and took more from it because it felt like Dennis wasn’t the only coach involved in the process. He didn’t take a cookie-cutter approach to bowling either – working from the base of a safe action and expanding from there. Instead, he wanted to work from my strengths as a bowler and harness those, while finding some efficiencies. One of the base principles of his coaching ethos is that the player has to be their own coach, and that idea really resonated with me. Dennis taught me a lot, and the thing that he stressed while working with me and the thing I remember most vividly is that you have to be able to take advice from coaches like him and make it your own.

Some people respond differently to different coaches and players, and that’s part of the direction to training I wanted to take the team – respecting their needs as individuals instead of taking a cookie-cutter approach. As a bowler, I can have high-level conversations with some of the batters, but maybe that’s going to be better – or better received – coming from a coach who has been a batter for twenty years. Although this is not an admirable quality, I know I’m cynical of advice on technique from non-bowlers unless I think they know what they’re talking about.

I’ve had great coaches who never played the game at the top levels, and I’ve seen great former players who weren’t much chop as coaches, but there’s nothing quite like a great player who is now a great coach. I reckon Dennis is one of those because he vividly remembers what it was like being a player but knows that he’s not going to be out there on the pitch anymore.

A great coach doesn’t rant and rave; they instil in their players a sense of personal responsibility. The cricketers have to play the game, to fight for their successes and accept their failures, and no coach – or administrator, commentator or fan, for that matter – can do that for them. You can get all the advice in the world from trusted professionals, and a lot of that advice cancels each other out, so in the end it is about the individual to trust themselves and steer their own path. I took a lot from Dennis, and he helped me really get my career going, but one of the most important things I took away was his idea of what it means to be a player who takes responsibility.

My bowling did change when I was working with Dennis, and mercifully I haven’t continued to suffer the chain of injuries that I did when my career started, but my perspective changed too. People like Dennis Lillee are in a continuum of the continued improvement of the game, improvements that I have benefited from. I hope to be part of that continuum, and I hope one day I’ll be able to help some other young cricketers when they’re preparing to be out in the middle.

This excerpt from Pat Cummins’ ‘Tested’ has been published with permission from Harper Collins Publishers.

This excerpt from Pat Cummins’ ‘Tested’ has been published with permission from Harper Collins Publishers.