The 2016 demonetisation exercise, announced by the Government of India, was a bold policy aimed at addressing systemic issues such as black money, counterfeit currency, terror financing and corruption, while fostering a transition to a cashless economy. Despite its ambitious objectives, the exercise was marked by significant disruptions, contradictions and limited success. Internal deliberations of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and subsequent data revealed substantial gaps between the government’s claims and actual outcomes.

The CAG initially announced (2017) that it would examine the subject but shortly thereafter, for reasons unknown, backed out. This chapter critically examines the demonetisation exercise, its stated goals, procedural flaws and the achieved results, attempting to provide a comprehensive analysis supported by data and evidence.

The Government’s Rationale for Demonetisation

On 8 November 2016, the government declared ₹500 and ₹1,000 currency notes invalid, removing approximately 86% of cash from circulation. The stated objectives were eliminating black money held in cash, curbing counterfeit currency, disrupting terror financing and corruption, besides promoting a cashless economy by accelerating digital payment adoption.

The government’s affidavit to the Supreme Court presented these justifications:

- High cash in circulation (CIC) was linked to systemic corruption.

- Counterfeit currency posed a significant threat to economic and national security.

- High-denomination banknotes were allegedly used for storing black money.

Despite these claims, internal deliberations of the RBI and subsequent events revealed discrepancies in the government’s rationale and highlighted challenges in implementation.

Key Discrepancies and RBI’s Concerns

(i) Currency in Circulation (CIC) and GDP The government argued that India’s high CIC-to-GDP ratio (12% during 2011-2015) indicated corruption and excessive cash dependency, comparing it unfavourably with the US (7.4%). However, post-demonetisation, the CIC-to-GDP ratio rebounded to 12% by 2019-2020 and further rose to 14.4% in 2020-2021. This suggested that demonetisation had no lasting impact on reducing cash dependency.

(ii) Quantum of Fake Currency The government emphasised that counterfeit currency was a pressing issue impacting economic stability. However, RBI data revealed that fake currency constituted only a negligible portion of the ₹17 lakh crore cash in circulation before demonetisation. Redesigned ₹500 and ₹2,000 notes were also counterfeited soon after their introduction.

(iii) Black Money and High Denomination Notes

While the government claimed that black money was predominantly held in cash, particularly in high-denomination notes, the RBI countered that most black money was stored in non-cash assets such as real estate, gold and offshore accounts. This rendered demonetisation largely ineffective in targeting unaccounted wealth.

(iv) Timing and Preparedness

The government presented demonetisation as a well-planned exercise. However, RBI minutes revealed that the Task Force for recalibrating ATMs was set up only after the announcement had been made. This lack of preparedness led to prolonged cash shortages and logistical chaos, disproportionately affecting rural and cash-dependent populations. Defenders would say secrecy was paramount for the scheme to have an effect.

(v) Growth of Cash Circulation vs. Economic Growth The government compared the nominal growth of cash circulation with real GDP growth, claiming it showed disproportionate cash growth. However, the RBI clarified that when adjusted for inflation, the disparity was minimal, thereby weakening the rationale for demonetisation.

- vi) Impact on Terror Financing The government asserted that demonetisation would disrupt terror financing by invalidating counterfeit notes. However, the Reserve Bank of India’s internal deliberations did not cite this as a primary rationale. Evidence suggests that terrorist networks quickly adapted to the new currency.

(vii) Implementation Challenges Significant logistical issues hindered the execution of demonetisation. Delayed recalibration of ATMs exacerbated cash shortages. The slow pace of remonetisation disrupted the informal economy, which relied heavily on cash transactions.

Actual Outcomes

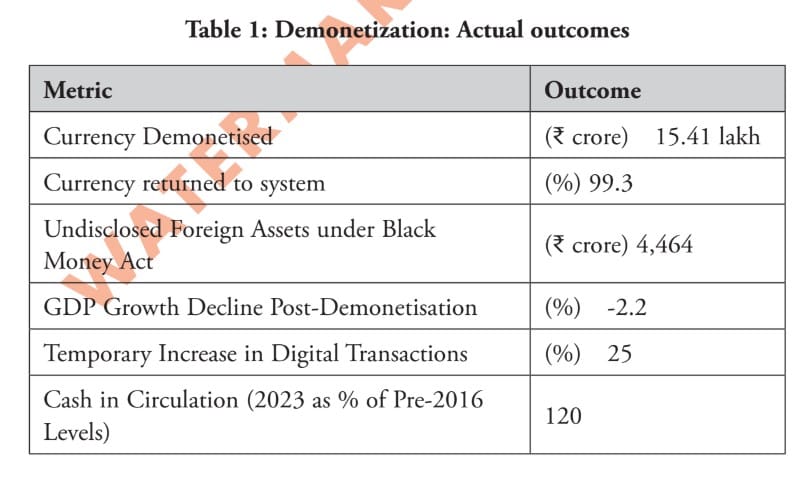

The outcomes of demonetisation diverged significantly from its stated objectives17, as illustrated by the following data:

Table 1: Demonetization: Actual outcomes

Nearly all demonetised currency (99.3%) returned to the banking system, indicating that black money holders found ways to legalise their cash. Digital transactions surged temporarily by 25%, but cash usage rebounded quickly, with cash in circulation reaching 120% of pre-demonetisation levels by 2023. This contradicted the government’s claims of reducing cash dependency. In contrast, the Black Money (Undisclosed Foreign Income and Assets) and Imposition of Tax Act, 2015, uncovered ₹4,464 crore of undisclosed foreign assets.

This targeted approach proved more effective than the sweeping demonetisation exercise in addressing black money.

Also read: Demonetisation, GST, RBI legacy—The importance of being Shaktikanta Das, Modi’s new principal secy

Judicial and Procedural Concerns

RBI’s Autonomy and Process

Under Section 26(2) of the RBI Act, demonetisation required an independent recommendation from the RBI. Evidence suggests that the government initiated the process, with the RBI merely acting as a rubber stamp. It undermined the principle of central bank autonomy and raised questions about procedural legality.

Judicial Evasion

The Supreme Court’s delay in addressing the constitutional challenge to demonetisation rendered the issue largely academic. The lack of transparency, including the withholding of key documents, further weakened public trust in governance.

Conclusion

Demonetisation, while bold and ambitious, largely failed to achieve its stated objectives. It caused significant economic disruption, particularly in the informal sector, and exposed serious flaws in both planning and execution.

The RBI’s internal concerns, which were ignored by the government, highlighted procedural lapses and questioned the efficacy of the exercise. By contrast, targeted measures such as the Black Money Act18 of 2015 proved more successful in addressing unaccounted wealth.

Ultimately, demonetisation serves as a cautionary tale, emphasising the need for evidence-based planning, institutional autonomy and transparency in policy making.

The CAG missed out on examining a very seminal and bold initiative despite announcing that it would do so. I will now discuss a very significant topic: the risk assessment process adopted by CAG (or at least supposed to have been adopted) while deciding on subjects for performance audit. Unless this process is robust and consistently applied to the selection of audit topics, very significant initiatives or programmes of the Government might be completely overlooked, leading to avoidable questions about the objectivity and transparency of CAG’s performance audit process.

This excerpt from P Sesh Kumar’s ‘CAG: What It Ought to be Auditing?’ has been published with permission from White Falcon Publishing.

This excerpt from P Sesh Kumar’s ‘CAG: What It Ought to be Auditing?’ has been published with permission from White Falcon Publishing.