We had been pursuing Bofors—after having looked down upon, or at the least, neglected the matter for long, The Hindu had hit the jackpot: it had received telltale documents from the Swedish investigator. We had nailed the Fairfax forgery. We had established Ajitabh Bachchan’s violation of FERA (Foreign Exchange Regulation Act). We had established that Reliance had violated several laws as they stood at the time, and it could not have done so but for the government’s complicity. We had been publishing material about the misdeeds of other friends of Rajiv, like Satish Sharma.

The government had retaliated by slapping us with notices alleging violations of various regulations and laws; by holding up newsprint; by instituting cases; by raiding the residence of Ramnathji and our offices. They had physically stopped the publication of our principal edition, the one in Delhi.

None of this had deterred us, none of it had even slowed us down.

Most of the press was, as is always the case, singing hosannas of the rulers—Rajiv Gandhi and his circle. With his overwhelming majority in Parliament, and the Opposition’s inability to get together, Rajiv had little more than condescension for it. ‘There is no Opposition,’ he said. ‘There is just one newspaper.’

We were that paper.

One day, 28 August 1988, with just two days left for the session to end, the Question Hour of the Lok Sabha had but to conclude, and a Bill was thrust upon the House—‘The Defamation Bill, 1988.’ Members were told that there would be no Zero Hour, that they had half an hour to table amendments, that the Bill would be taken up as soon as the House met after the lunch break. The Bill had just been sprung on them: it had not been so much as mentioned at any meeting of the Business Advisory Committee. It was evident that the government was determined to ram the Bill through the House that very day. The Opposition was up in arms. Hulla ensued. The government agreed to continue the discussion till the next day.

And rammed through the Bill was the next day. The government let it be known that it would take the Bill to the Rajya Sabha forthwith.

The government was asked repeatedly, in Parliament and out, what had happened which made defamation such an urgent matter. It offered no explanation. The government was asked what was about to happen which made it necessary to stop that event from happening immediately through a new law. It offered no explanation. During the debate, the government was asked to provide illustrations of the kind of publications that it thought were so indefensible and which, in its view, could not be dealt with by existing laws that a new law was required to curb them. It was not able to provide any illustrations. During the debate, Somnath Chatterjee, the CPI(M) member asked the minister piloting the Bill, P. Chidambaram, to provide just one illustration, just one. The government was not able to provide even one illustration. The demand was repeated outside Parliament. The government was not able to provide any illustration.

Asking for an illustration was just a way of putting the matter. There was no doubt about what sort of work the government wanted to throttle. Nor was there any doubt that the government could not cite that kind of work as an illustration of the kind of writing that just had to be stopped!

We realized that the Bill had to be stopped. Indeed, that it had to be killed ‘in broad daylight’, so to say—to be killed so conspicuously that future governments must not think of ramming through such legislation. But we also realized that the Express could not do so by itself. There would have to be a campaign involving the entire press. The campaign must be such that even the pro-government papers would feel compelled to join it.

And Ramnathji spelt out the sine qua non for organizing such a campaign. ‘Andolan karnaa padegaa,’ Ramnathji said. ‘Toofaan khadaa karnaa padegaa.’ Of course, that was exactly what we thought had to be done. But he hadn’t finished. ‘Aandolan to hamein he karnaa padegaa; toofaan to hum sab ko hi uthaanaa padegaa. Par hamey aagey naheen aanaa hai. Har ek press-waaley ko lagey ki aandolan voh he chalaa rahaa hai. Tum sab peechey rehnaa. Main bhee peechey he rahoongaa. Irani ko aagey karo—usey leaderee kaa bahut shauk hai, apni photo khinchwaaney kaa bahut `k hai. Usey leader banaayogey, voh bahut phoolegaa. To jo chaahengey, voh karegaa, aur auron se karvaaega.’

Also read: Guns, Swedes and the Gandhis — how the Bofors scam tested the limits of the CBI’s power

The campaign

Journalists rose as one man. Dharnas, processions, articles and editorials in their papers. Walkouts at press conference after press conference. Blank editorial space encased in a black border. Refusal to accept awards from the hands of ministers. Journalists began wearing black badges. The highlights were a procession from India Gate to the Boat Club—Ramnathji, Irani, editors of all leading newspapers and magazines, everyone was there. And then a nationwide shutdown of all publications.a

Rajiv Gandhi helped as he swung between seeking a way out and sticking to the last. I have an open mind, he would say one day. Let the press come and convince me. And then that he was convinced that the Bill was necessary, that the government was moving in the right direction, that those opposing the Bill had not read it, he would say, all there is, is haahaakaar . . . One day his minions were all determination. The next that the Bill is not being introduced in the Rajya Sabha as planned, that is on the next working day. Then that it is not going to be introduced pending a comprehensive dialogue with all sections, in any case, not in this session . . . Every twist added fuel to the journalists’ engines.

Members of other professions joined: lawyers, trade unions. And the Opposition parties. N.T. Rama Rao announced that Andhra would disregard the Bill should it become an Act. Fissures developed in the ranks of the Congress itself. Kamlapati Tripathi, former Chief Minister of UP and a senior leader, declared that the government should withdraw the Bill. The authors began to distance themselves: Chidambaram was visible much less; Siddhartha Ray, then Governor of Punjab, had a statement put out by his Secretariat that he had not contributed to drafting the Bill.

It really became a national stir. The cause was not just to get one Bill withdrawn. It was not just the freedom of the press. It wasn’t even just the right of the reader to know facts about his rulers. The cause now was to ensure that rulers listen to the people. It was time to remind people of what Gandhiji had written in regard to the Rowlatt Bills.

The Bills are bad in law, he had said. But worse, they are an insult to the whole nation, he had said, as they are being ‘steamrollered by means of the official majority of the government and in the teeth of the unanimous opposition from the non- official members’. After the speech of the official representative reaffirming the government’s faith in the Bills, ‘It is necessary,’ he told the private secretary to the Viceroy in a telegram, ‘to demonstrate to government that even a government [of] the most autocratic [kind] finally owes its power to the will of the governed.’ ‘The Bills require to be resisted not only because they are in themselves bad,’ he told the thousands who had gathered to hear him in Madras, ‘but also because government, which is responsible for their introduction, has seen fit to practically ignore public opinion and some of its members have made it a boast that they can so ignore that opinion . . .’

‘It is common cause throughout the length and breadth of India,’ he told the audience in Tuticorin, ‘that that legislation, if it remains on the Statute-book, will disgrace the whole nation. We have asked our rulers not to continue that legislation. But they have absolutely disregarded the petition. They have therefore inflicted a double wrong on the whole nation. We have seen that all our meetings, all our resolutions and all the speeches of our councillors have proved to be of practically no avail . . .’ And, therefore, he said in a written message, ‘To my mind the first thing needful is to secure a frank and full recognition of the principle that public opinion properly expressed shall be respected by the government.’

Also read: That funny Bofors feeling

The outcome

With every passing day, it became clearer and clearer that the parable L.K. Advani used to repeat would come true for Rajiv Gandhi.

A criminal was caught and brought to the presence of the ruler. But the ruler was in a magnanimous mood that day. ‘I will give you a choice,’ he announced to the criminal. ‘You can either choose to eat a hundred onions or to be flogged a hundred times.’

‘God, a hundred lashes of the whip will be too much,’ the criminal thought. ‘Jahaanpanhaa, I will eat the hundred onions.’

He had barely eaten ten and his mouth was ablaze, his eyes dripping with tears. ‘The whip won’t be as awful,’ he moaned.

He pleaded that he be exempted from eating the remaining ninety onions, and that he would rather suffer the hundred lashes.

The King, in his magnanimity, accepted the plea.

The criminal had suffered but ten lashes, and he screamed, ‘Please, please stop this flogging, I will eat the ninety remaining onions.’

And so it went: onions . . . lashes . . . onions . . . lashes . . .

By the end, the poor fellow had eaten the hundred onions and also suffered a hundred lashes.

On 22 September, just three and a half weeks after he had rammed the Bill through the Lok Sabha, Rajiv’s government announced that the Bill was being dropped altogether.

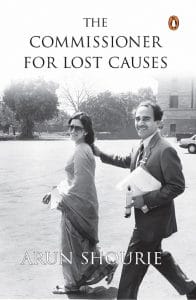

This excerpt from ‘The Commissioner for Lost Causes’ by Arun Shourie has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

This excerpt from ‘The Commissioner for Lost Causes’ by Arun Shourie has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.