In 2003, Justice Ahmadi was asked to assume the distinguished role of Chancellor at Aligarh Muslim University, a position that he held for two consecutive terms. During his tenure, Ahmadi went beyond the ceremonial duties associated with the role of Chancellor. A fervent advocate for the transformative power of education, he lent his voice to the cause on various public platforms. But there was a legal matter too. Coinciding with his term as head of the University was the raging debate surrounding the minority status of the institution – a matter of great angst within the Muslim academic community.

The debate, nuanced and complex, reflected the broader challenges faced by educational institutions in grappling with issues of identity, representation and community aspirations. During his own tenure as Chief Justice of India, Justice Ahmadi had taken the proactive step of convening a special eleven-judge bench to re-examine the interpretation of minorities’ educational rights under Article 30 of the Constitution, hoping to resolve the issue before his retirement. Judiciously, he had kept himself off this bench.

Recognizing the significance of the matter, Tahir Mehmood who was Chairman of India’s National Commission for Minorities at the time advocated for the body’s formal involvement in the case as amicus curiae. However, delays from the government’s end resulted in the case remaining unresolved until Ahmadi demitted office. This was indeed unfortunate, as the issue became hopelessly tangled in later years.

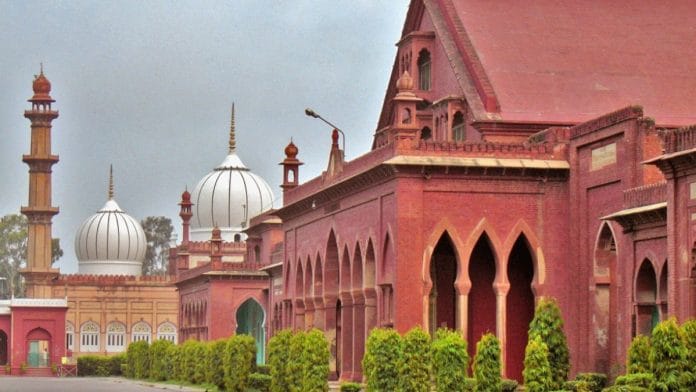

The history of Aligarh Muslim University is more than a century old. In 1877, Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, a 19th-century Muslim reformer, established the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College (MAO College) in Aligarh, aiming to promote modern British education among Muslims while preserving Islamic values. The Aligarh Muslim University Act of 1920 (AMU Act) merged the MAO College and another Muslim University Association into one institution known as the Aligarh Muslim University (AMU). The University’s governing body, known as the Court of the University, was required to comprise exclusively individuals belonging to the Islamic faith. But subsequent amendments in 1951 and 1965 altered its structure. Financial challenges faced by the AMU in later years led the Government of India to take over its maintenance, transforming it from an aided to a maintained institution.

The 1951 amendment eliminated compulsory religious education for Muslim students and removed the provision enforcing only Muslim representation in the Court In April 1965 when violence erupted during an AMU Court meeting, leading to the humiliation and injury of Vice-Chancellor Ali Yavar Jung, the Education Minister, M.C. Chagla pushed through an amendment, known as the AMU (Amendment) Act of 1965, granting extensive control to the Central Government.

This amendment effectively placed executive and administrative control in the hands of the Visitor, typically the Union Minister of Education, and sidelined the University Court. The 1965 Act raised questions about the AMU’s status as a minority institution under Article 30 of the Constitution, which grants minorities the right to establish and administer educational institutions of their choice. In response, Muslim organizations appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that the 1965 Act violated the AMU’s constitutional protection as a minority institution.

The pivotal S. Azeez Basha case in 1967 challenged these amendments, asserting violations of educational, religious and cultural rights. However, the Supreme Court upheld the changes, stating that AMU wasn’t solely established or administered by the Muslim minority. But then in 1981, the AMU Act was amended once again to redefine the University as an institution ‘established by the Muslims of India’.

Government representatives in Parliament hinted at restoring AMU’s ‘minority character’ without explicitly committing to it. This implied a legislative basis for considering AMU as protected under Article 30(1), satisfying both parties without a firm assertion. But when the University reserved 50 per cent of medical seats for Muslim candidates in 2005, its minority status once again became contentious.

Legal battles ensued claiming that the educational institution was a secular one, with the University contending that S. Azeez Basha was nullified by the 1981 amendment, and therefore it was permitted to make provisions for the benefit of Muslim students. But the Allahabad High Court rejected the University’s claim. In 2006 the Supreme Court, stayed the reservation policy and later referred its constitutionality to a larger bench.

Since then, the issue has remained contentious, prompting a reconsideration of the S. Azeez Basha decision by a seven-judge bench in 2019. In October 2023, a bench led by CJI D.Y. Chandrachud convened to re-examine the matter, delving into the intricate history and legal nuances surrounding the Aligarh Muslim University’s governance. At the time of writing, the matter is still undecided Justice Ahmadi’s views on this were, however, unambiguous. ‘I have no doubt in my mind that the character of AMU is that of minority institution.

But unfortunately over a period of time some judges in the Supreme Court and in the High Court gave their own interpretation.’ He also believed that the Azeez Basha judgement was flawed and not in keeping with the principles of natural justice.

‘Now if you look at the Azeez Basha case it was deciding on the character of the university and the university was not made the party in that. The basic tenet of law that natural justice has to be done and for the purpose of deciding the character of the university, it was important that you have the university before you as a party to defend its character. The larger bench hearing should be fixed as early as possible.’

In a speech made in the capacity of the Chancellor of the University, he stated:

Every dark cloud has a silver lining, and so does this, because it gives the University an opportunity to question the correctness of the decision in Azeez Basha. It is a thorn which will pinch again and again.

Because of the view taken by the Division Bench on the competence of Parliament to amend the 1920 Act in view of the Entry 63 in List 1, there is no alternative but to challenge the decision in the Apex Court. As I said, there are flaws in the judgements of the learned Single Judge as well as the Division Bench, and I do hope a larger bench of the Apex Court will correct them.

In this speech, Justice Ahmadi makes reference to the seventh schedule of the Indian Constitution, which outlines the division of powers between the union and states through three lists: Union List, State List, and Concurrent List. The Union List (List 1) empowers Parliament to legislate on specific subjects, while the State List (List 2) delineates areas under state legislatures’ authority. Entry 63 of List 1 includes Aligarh Muslim University, Benares Hindu University (BHU) and Delhi University and refers to them as institutions of national importance.

Because these universities were established through an Act and fall under Entry 65 of the Union List, any changes to their administration will have to be codified in the statute through the Parliament. Any new legislation or changes in existing laws regarding these two universities would have to be enacted by the Central Parliament.

Justice Ahmadi has termed the view of the Allahabad High Court as ‘grossly erroneous,’ stating that he was sure the central government would make every effort to have it reversed, ‘. . . otherwise it will be forced to go in for a constitutional amendment as it would also reflect on the Parliament’s power to amend the Acts concerning the other two universities, the BHU and the University of Delhi.

In his personal writings, Justice Ahmadi also makes mention of attempted interference in the affairs of the Aligarh Muslim University by the Ministry of Human Resource Development. During his first term as Chancellor, he was compelled to remind the ministry that the University was regulated by the Central University Statute and therefore their interference in the admission process was unwarranted.

A similar situation arose when the ministry invoked the UGC and attempted to interfere in the financial management of the University – another attempt that was blocked by Ahmadi. In these writings, Justice Ahmadi expresses the hope that those at the helm of the University will be able to stand strong and resist attempts at political meddling, which have the potential to dilute the University’s autonomy.

This excerpt from ‘The Fearless Judge: The Life and Times of Justice AM Ahmadi’, has been published with permission from Juggernaut Books.

This excerpt from ‘The Fearless Judge: The Life and Times of Justice AM Ahmadi’, has been published with permission from Juggernaut Books.

AMU is not only a minority institution but a privileged elite minority within a minority institution.

Instead of exposing ex-CJI AM Ahmadi, Ms. Vahanvaty is celebrating him. Instead of exposing AMU for the conception of the idea of Pakistan and providing leadership to the Pakistan Movement which led to the partition of India, Ms. Vahanvaty seems more interested in the “minority character” of the University.

An institution like AMU must be held accountable for it’s role in the creation of Pakistan.