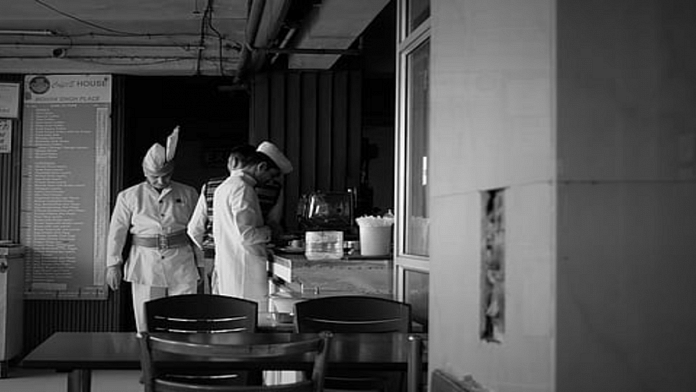

Parasnath Chowdhary impressed upon me just how special and unique a place the coffee house was. ‘It was such a thriving, beautiful place. It offered you all kinds of experiences. You cannot even hold these experiences, you cannot describe, they are incapable—I learned so much.’ He offered by way of comparison,

“I was at Monparnasse in Paris and I went to some coffee houses and I could not find the same atmosphere. It was much more lively [in Delhi]. The coffee houses in Paris were much less lively, less happening, than the coffee house I experienced in Connaught Place. I tell you, it was one of the most powerful coffee houses in the world. I wish you would have seen it and partaken of it.”

Rajkumar Jain had similar praise for the space. He told me,

“There was some sort of glamour in going to coffee house. If you are going to coffee house, it means you are a sensitive person, you are a literate person, you are interested in day-to-day political development or something. And to get the knowledge, latest knowledge of that thing what is going on. And the beauty of that thing is that even the top hierarchy of various political parties, they used to come and enjoy at the coffee house. So kophi bahane ko kya bolte hain? (How do you say ‘coffee was just an excuse’?)”

Also read: Delhi University at 100: Staging ground of history, scholarly success & coffee-shop romances

He continued by summing up his feelings of attachment to the Indian Coffee House at Connaught Place,

“So, that time if I didn’t go to Connaught Place, I used to feel empty, lost, don’t know what has happened, as I have not been to coffee house. It was such a need of a mind. Without going to the coffee house, I am not connected to the current affairs, I am lost, I must go. So one easy link within reach, very cheap also, no restrictions, whether you take coffee or not, spend money or not, whole day, it was a place where you can sit idly the whole day, nobody will disturb you. That was also also a reason, because you have got at least one place. Fourth, it was a meeting centre, people would say we would meet at the coffee house. And it was an only centre where all sorts of magazines and newspapers and periodicals and all intellectual things, you will find there. So people used to come and watch there. And there used to be a paan-walla (betel-nut seller) shop. They used to take paan also there. That way, coffee house was a place of political gossip, intellectual discussion, enjoying, meeting friends. But the tone of that coffee house was anti-government. I have just narrated you the general things to set the scene. You know that was a place full of democracy. People are shouting, their one table, sitting there, shouting like anything, big talking, another table you will find that a different discussion is going on. Nobody is bothered, everybody is enjoying his own.“

Parasnath Chowdhary explained to me that while he and his closest friends who used to meet in the Indian Coffee House were Socialists,

“It wasn’t only Socialists. People of all political views came to [Indian Coffee House]. It was a mass meeting kind of a thing. Everyday, a mass meeting would take place. But a mass meeting not of one opinion, but of many opinions. There was not one political party that was not represented there. That was the character of this coffee house. It was a highly, as I said, happening place, representing all sections of society. And, you see, the minute you go there, you feel that the place is promoting discussion. You start to enter into discussions. You cannot help discussing things the minute you are there. That was the vibe. The vibrations were so positive that immediately you enter into a discussion. And it was a loud and animated discussion. It was never a low decibel discussion. I call it a furtherance of democracy.”

Said Dillip Simeon, who had just emerged from the Maoist underground in 1974,

“That was where our politics of the whole age took place—Maoism, Naxalism, etc. That was the coffee house in Delhi and that was the centre of all these radical discussions. Innumerable cups of coffee were consumed over there by radicals deciding the fate of humanity; [discussing the] Vietnam War, Naxalism, Maoist Revolution.… It was a fantastic atmosphere.”

Kamlesh Shukla also recounted how a wide range of political viewpoints were represented in the conversations that took place in the Indian Coffee House. He said,

“Many leaders would come and sit there, Members of Parliament would sit there, they belonged to political parties. Journalists would be meeting there with these Members of Parliament and with the Ministers for news, basically. And they would exchange notes in the coffee house, so people came to know what is happening in the government, what are the new trends happening, etc. etc. Socialist Party was there, Congress was there, the Right wing, what is known today as BJP, was known then as Jan Sangh, were there, though they hardly were there. Haan (Yes), yes, Communists used to be there. So generally, you could say left wing politicians would be there.”

P. Singh told me, ‘Coffee house culture was very important. It still is also.’ He continued, ‘The coffee house was where opinions were formed. For democracy, the coffee house is essential.’ He explained, ‘People of all types went there to discuss all the political aspects of everything that was taking place.’ He recalled fondly his conversations with Socialist politician Chandra Shekar. Even though Singh was a Communist, he still interacted with those affiliated with other parties. He said,

“Even Chandra Shekar, used to come to and I used to sit with Chandra Shekar. Chandra Shekar was an anti-government fixture in the Connaught Place coffee house. He used to come regularly, every two or three weeks. He was always criticising other leaders, he would even criticise Lohia.”

He added, “Nobody remembers that people like Chandra Shekar, they used to come there. Nowadays, politicians, they don’t want to come there.”

Lalit Mohan Gautam told me that the Indian Coffee House was the place where student politics happened in the late 1960s and in the 1970s. He said,

“You see, the entire student politics and youth politics in those days revolved around [Indian] Coffee House, especially in Delhi. But also in the small towns, whichever I visited, there were coffee houses, like Allahabad had a very popular [Indian] Coffee House. If you go to Allahabad near Civil Lines area, you will find a very popular coffee house near the University [of Allahabad].”

Ravindra Manchanda, a member of the Samajwadi Yuvjan Sabha (SYS), the youth wing of the Samyukta Socialist Party, and his fellow student activists would meet in the Connaught Place Indian Coffee House and strategise for their group and talk politics. Their professors and other professors from around Delhi who would also gather in the Indian Coffee House served as encouragement. Subhendu Ghosh similarly recalled that the Indian Coffee House was a key meeting place for those involved in student politics. He recounted,

“The Congress government didn’t allow us, their students’ wing used to do a lot of physical torture on us, and we used to face a lot of, [narrator takes audible sip of tea]. So sometimes it was good to go to coffee house and then decide the strategy. What should we do? It may not be that meaningful but, essentially, it’s student politics—plan demonstrations, protests, plan posters, this things, or sometimes plan meetings to recruit cadres, juniors, you know [narrator laughs], to politicise them [narrator laughs].”

He also confessed, “To tell you very frankly, I was hardly doing academics. I was spending most of my time in the coffee house.”

Also read: Indonesian wood, sustainable pieces, Italian imports — bespoke furniture is changing Indian homes

While Ravindra Manchanda cited the professors who gathered in the coffee house as an important source of encouragement for his student politics, Ramchandra Pradhan, who was teaching at Delhi University during the Emergency, told me that the older patrons of the coffee house who had participated in India’s Independence Movement were a similarly important source of inspiration for him and his friends. He told me that

“It [the Indian Coffee House] had all kinds of people, all intellectuals, and policy makers used to come to consult. Very good place. A lot of freedom, even for those days. It was a very free time, interactions— what JNU claims to be today. We had this kind of atmosphere in the mid-60s and a lot of free discussions, even Naxalites could come, you know. So there was an environment of some kind of freedom. It had become a basic kind of space for people like us. Then I started teaching also, in Delhi University. Why am I saying all this? Because it is a background. It’s a background. And for us, it was freedom, liberty, that was very important. Some kind of activists with SSP, Samyukta Socialist Party, [were there]. You see, at that time, Samyukta Socialist Party, SSP, it was led by Dr. Lohia, of course other people, some leaders were there [in the Indian Coffee House], some of the important leaders were Raj Narainji, George Fernandes, they were there. So the entire atmosphere was one of freedom. Now, all of them had their strengths. We were born after the Independence, so had not participated in the Freedom Struggle, but we closely interacted with the people who were in the thick of the fight. So of all this, contributed to our mental makeup in which the Freedom Struggle loomed large.”

The coffee house workers were another source of support and encouragement for political activists. Ravindra Manchanda told me that in the Indian Coffee House,

“The workers belonged mostly to Communist or Socialist ideas. The Communists had the workforce, they were very popular with the trade unions. So workers were by and large encouraging. There were some restrictions on them because they were working, they could not come and openly participate in our activities, but visible support was there from them, you know, on every issue. Like, sath sankar socialist logon slogan tha (seven revolutions was the slogan of the Socialists).”

He went on to explain that there was, during the Emergency, however, caution in the interaction between the workers and patrons because of a mutual fear of arrest. The workers ‘encouraged us and they—because everybody had their own limitation, you know? The fear of getting others arrested’.

P. Singh also told me a bit about the relationship between workers and Indian Coffee House regulars. He said, ‘The customers were politically aware people, and the workers were Party workers. CPI and CPI(M) people would come and they were discussing. They were discussing in the coffee house.’ He explained,

“During the split [in the Communist Party in 1964], most of the workers sided with the CPI(M), but the CPI leadership was still meeting in the coffee house. After the split, there was really no change in the coffee house. Everyone was used to having different opinions, so there was one more opinion.”

The Indian Coffee House also offered a space that evaded state surveillance. Subhendu Ghosh told me that this was an important consideration for student activists. He said,

“But the specialty of the coffee house is that they will not ask you who you are and from where you have come and why you are meeting here. They’re just concerned about what you want to drink and what you want to eat. That’s all [narrator laughs]. So, and coffee house by tradition they have maintained this culture. That’s how ’til late people dared to be there.”

This excerpt from ‘Brewing Resistance’ by Kristin Victoria Magistrelli Plys has been published with permission from Cambridge University Press.

This excerpt from ‘Brewing Resistance’ by Kristin Victoria Magistrelli Plys has been published with permission from Cambridge University Press.