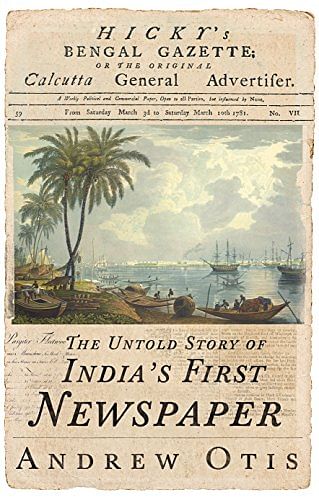

In Hicky’s Bengal Gazette: The Untold Story of India’s First Newspaper, Andrew Otis perpetually reminds his readers of parallels between the time then and now.

The story of James Augustus Hicky, as narrated by Andrew Otis, is a thoughtful excavation of South Asian media’s history. It combines excellent research and exquisite detail with a flair for fast-paced storytelling and leaves the reader, lay or academic, provoked into contemplation.

Otis deftly manages to impose a human, informal, tone upon the interested parties in the scandal that Hicky’s Bengal Gazette, the first paper printed in Asia, was and the scandal it gave rise to.

This charming readability prevents the book from being a stultified tome of partly reproduced archives.

Though essentially an assemblage of years of exhaustive research, the book is accessible and actively avoids academic jargon. This allows it to sustain the grip of the narrative.

But that is not the only reason it should be made compulsory reading. More importantly, throughout the book, the author perpetually reminds his readers that the consequences of Hicky’s tussle for information control with Raj honcho Warren Hastings still echo across South Asia more than two centuries later.

Otis meticulously locates a historical archival study in 21st-century terms of political violence and censorship regimes. It thus carves a place for itself in the disciplines of political science, literature, journalism, and history, to name a few. This is why it answers an urgent need for more studies on the region.

However, accessibility for the non-academic reader defines a narrative arc, and creates sets of protagonists and antagonists. It is necessary for reader interest to be maintained through the perusal of records but this comes at the cost of easy essentialism of the ‘characters’ involved in the ‘story’ of Hicky.

Hastings, John Zacharaiah Kiernander (the missionary who sued Hicky for libel), and Hicky emerge as titans vying for everything they hold dear. Otis admits this to be a red flag, and attempts to redress this slant. After he comes across Kiernander’s letters and published response to the scandal, he says, “I came to realise I might have become too sympathetic to Hickey at the expense of others.” (Otis xii)

But the weight of sympathy usually falls in favour of Hicky as the radical hero, pro-subaltern, wronged Samaritan of the freedom of the press. Otis says in the prologue, “For centuries he had been ridiculed as a scurrilous muckraker who insulted his social betters, not worthy of the title ‘journalist’.” (Otis viii)

The premise for this book is the misunderstood discourse and significance of Hicky’s ‘radical’ attempts at creating a platform for interested parties to voice concerns and grievances.

Moreover, given that media studies are finally being negotiated by myriad disciplines, it would have greatly benefited the book to have delved deeper into the print context of the late 18th century, especially the English satirists and Punch-style caricaturists.

It is clear that part of Hicky’s agenda derived its energy from the contemporary practice of caricature in writing and visual art. This would certainly have presented a more nuanced understanding of the pleasures and pitfalls of satire in public mediums.

These observations are meant to enable future work in this field. There is no doubt that the book is an important move in an area that needs immediate attention. One hopes that Otis’ engaging account will trigger such attention.

The writer is an assistant professor in the University of Delhi

COMMENTS