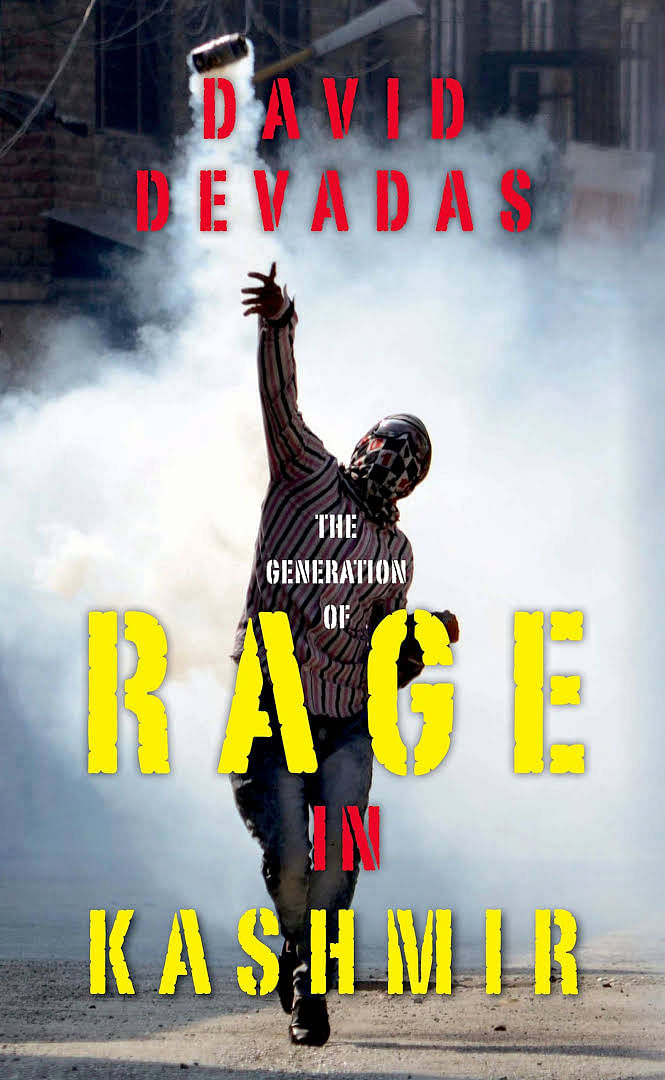

In his new book, David Devdas collates and analyses different responses of people living in the Valley and puts the rise of new militancy in context.

Among the troubling words that surfaced in a survey of 600 Kashmiri students about ‘azadi’ were: “slaves of India”, “humiliation” and “toys in the hands of Indian government and Indian military”.

David Devdas’s book, The Generation of Rage in Kashmir, brings multiplicity of voices from within and decodes that “nebulous concept” called azadi (freedom) that is largely understood as political aspiration of Kashmiris.

As the conflict in Kashmir takes a new turn with tabloids and media outlets full of debates and discussion on the wave of ‘new militancy’, Devdas asked the students questions based on the idea of azadi, women’s rights, sectarianism, among others.

Of these questions, the responses on azadi bring out a menacing sense of deprivation and betrayal that the youth in the Valley has experienced compared to their counterparts elsewhere. The plurality of responses on azadi ranged from “liberty to live with dignity, rights and without humiliation” to freedom from “nasty imposition” of the army all over and freedom from the “humiliation to prove their identity to an outsider”.

Also read: The new Kashmiri militant has a new target: Policemen on leave, at home

In this framework of “rights, benefits and environment free from fear”, most respondents identified themselves distinctly as Kashmiri. The responses reflected a “deeply embedded Kashmiri identity based on language and geography”. While culture and language were the main responses, there were few overtly political responses such as “slaves of India” and “toy in the hands of Indian government and Indian military”.

It is this political response that takes us back into the history of brutalisation of this identity at the hands of the “counterinsurgency apparatus” of the state, which most Kashmiris perceived as a “regime of harassment and humiliation”. The continued existence of counterinsurgency apparatus built anger in the younger generation that grew up listening to the narratives about the tactics of “killing, maiming, blackmailing and extortion” in the 1990s. As India became a security state with the assassination of former PM Indira Gandhi, the corridors of power ignored the fact that “security could oppress and alienate citizens, generating processes that decreased national security”.

Around this militarisation of the state, the book opens up a Pandora’s box, giving a comprehensive account of the most brutal conflict of South Asia. Based on his interactions with youth across the Valley, Devdas brings into perspective the current escalation of conflict, mass demonstrations and stone-pelting. Describing the life of those born and raised in a time of violence, who now comprise more than two-thirds of the Valley’s population, Devdas poignantly writes, “to Kashmiris who grew up during those years, India was the army”.

The book comes at a time when the discourse on the Kashmir conflict is highly militarised and polarised. The author painstakingly collated and analysed the different responses of people living in the Valley while contextualising the factors that led to the rise of new militancy. The book that presents a nuanced account of the conflict is useful for those whose decisions and policies impact the public opinion on ground. It is also an essential read for the layman who has sweeping opinions about Kashmir and Kashmiris without an iota of knowledge about the place, people and their history.

Adil Bhat is assistant editor with New York-based magazine ‘Café Dissensus’.

Also read: 5 reasons why Imran Khan can offer only empty talks & no resolution on Kashmir

Reviewer has got the name of the author wrong. It is David Dev(A)das. He has referred to him as Devdas.