American historian Stephen Dale’s book goes to great lengths to uncover Babur — the man and ruler, the strategist and the patron of arts.

When the Ram Janmabhoomi movement was at its peak “Babur ki aulad o ko ek dakka aur do” (One more push to the sons of Babur) became a popular rallying cry. Even the recent popular Netflix original, Sacred Games, echoed this narrative. A protagonist in the show reiterates that all the “unwanted sons of Babur” should be thrown out of India.

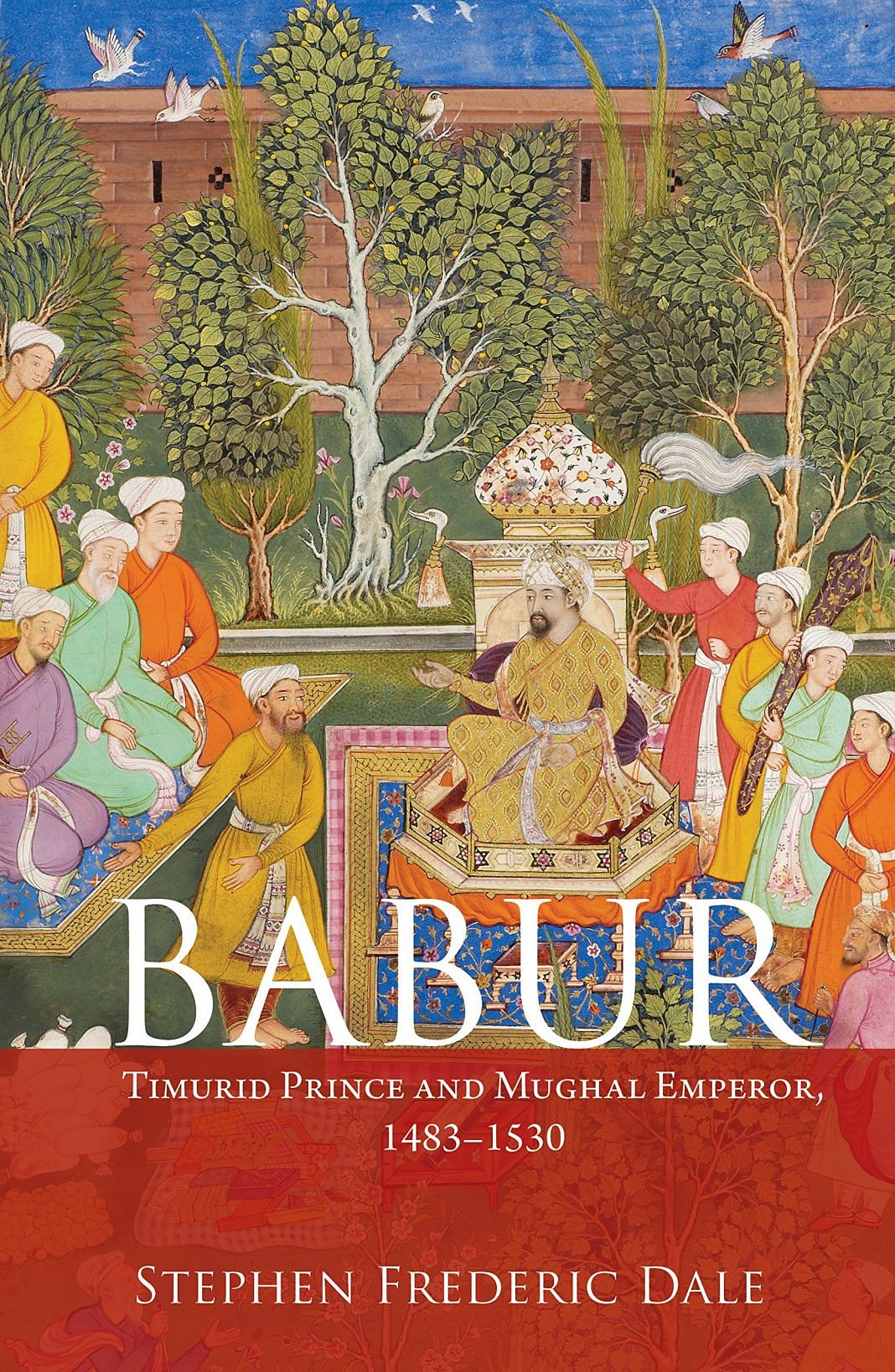

Babur has become a much-maligned character in history. He is perceived as the quintessential evil invader, the progenitor of all the ‘foreigners’ and ‘outsiders’, read Muslims that live in India. In this political climate, author Stephen Dale goes to great lengths to uncover Babur — the man and ruler, the strategist and the patron of arts.

Dale’s book Babur: Timurid Prince and Mughal Empire tells the compelling story of an emperor who led a life of contrition and tragedy. Dale, compelled by the desire to make Babur more accessible to people of South Asia brings alive the culture as seen through the eyes of the Timurid.

Babur ruled over a vast empire that sustained for more than three centuries. While the British have been some of the best historians chronicling South Asia, Dale, an American historian, approaches the subject with a unique perspective and a new method of historiography.

The author traces Babur’s journey and his changing observations and evolving convictions as he travels from Samarqand, Herat, Kabul to Hind. The book is filled with fascinating accounts of these travels. Accounts have also been taken from his military generals and court historians who lived a nomadic life, characteristic of the Chagatai Mongols. Babur never saw himself as a Mongol but rather more closely related to his Timurid side and would have been horrified to know his dynasty would be defined by the name of Mongols.

Dale makes a concerted effort to keep the prose fast-paced, focused on Babur’s life and his style of governance. Dale is a seasoned historian and has written five books on Islamic society and culture, including one on Ibn Khaldun, one of the earliest historians.

The book ends on a tragic note as Babur, who was never at home in Hind, dies dreaming of his boyhood city of Kabul.

“Sometimes, like madmen, I used to wander alone over hill and plain; sometimes I wandered in gardens and suburbs, lane after lane.

“My roaming was not of my choice; nor could I decide whether to go or stay. Nor power to stay was mine, nor strength to part;

“I became what you made of me, oh thief of my heart.” – Baburnama

Arghya Sengupta works at Juggernaut Books. Views and opinions are his personal

COMMENTS