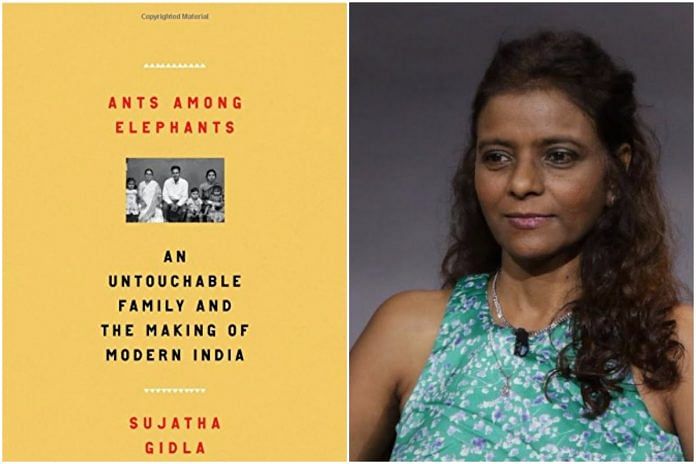

‘Your life is your caste, your caste is your life’, writes first-time author Sujatha Gidla, who has been unable to escape caste ostracism even in faraway USA.

Sujatha Gidla’s book ‘Ants Among Elephants’ is a fascinating account of the author and her family’s tryst with caste in the backdrop of radical movements—the Telangana Armed Struggle (1946-51) and the Naxalite movement under the CPI (People’s War Group). Her uncle, K.G. Satyamurthy, played a significant role in both.

The book highlights the character of caste in India. Even in the 21st century, the situation has not changed, despite religious conversions. Dalit converts are treated as outcastes not just by Hindu society, but also by their own community. Evidence shows that conversion to Islam, Christianity, Sikhism, and even Buddhism, didn’t help escape oppression.

Third-generation learners

Gidla’s family of third-generation learners makes it unrepresentative of a majority of Dalits, who are illiterate and earn their livelihood through manual labour. Yet, despite having achieved this relatively exceptional status, the family continued to face humiliation, highlighting how acute discrimination is.

Her grandfather, Prasanna Rao, along with two of his brothers, was educated in the mission school, and both her parents were college teachers. Despite being educated, she and her family were daily subjected to reminders of their caste status. Her mother, Manjula, struggled in the Banaras Hindu University because a Brahmin professor gave her poor grades. The professor realised that “she was poor and untouchable” and reacted with disgust. She was also rejected from teaching posts for similar reasons.

Gidla’s uncle Satyamurthy felt himself “an ant among elephants” in college, and was cruelly dumped by a well-to-do young woman named Flora, who had started a flirtation with him, only to announce: “We are Brahmins. You are have-nots, we are haves. You are a Communist. My father is for the Congress. How in the world can there be anything between us?”[p. 72]

On caste, Gidla says “you cannot avoid this question” — “you can tell the truth and be ostracised, ridiculed, harassed,” or “you can lie”.

“If they don’t believe you, they will try to find out your true caste some other way. They may ask you certain questions: ‘Did your brother ride a horse at his wedding? Did his wife wear a red sari or a white sari? How does she wear her sari? Do you eat beef?’ If you get them to believe your lie, then you cannot tell them your stories, your family’s stories. Because your life is your caste, your caste is your life.” [p. 4,5]

The titular “ants among elephants” allegory is indicative of the inferiority caste manifests among Dalits. Gidla depicts people from her community and her lived experiences with fine, luminous details.

Radical politics

One factor distinguishes Gidla from the rest—that she had a background of radical politics. She has marvellously woven together her family narratives with Indian politics, with the backdrop of caste inequality. Perhaps her own tryst with radical politics has helped her understand how both coexist together. Inspired by her uncle (Warangal was a hub of the RSU and PWG activists, where she grew up), she plunged into Naxalite politics. She was arrested, tortured and incarcerated in jail for three months at REC Warangal.

This account may be better read with this perspective.

The debacle faced by the movements of Dalits and communists, pursuing the binaries of caste, is primarily due to their failure to comprehend the character of either. Ambedkar and Marx had different ideological foundations, which were not easy to reconcile. A revolutionary movement should not rely upon such icons, which might make it sectarian. The communists committed a grave mistake in not confronting the Indian reality, and tried to fit it into Western moulds mechanically. It was not to lend primacy to caste or class, but to wage anti-caste struggle as integral part of the class struggle.

Caste could not be pitched against class, simply because while it is a concrete reality, it tends to abstract itself in process of seeking hierarchy that fundamentally characterises it. Other problems apart, even to bind all Dalits together on the basis of caste identity would be a difficult task. Gidla writes about how Pakis and Madigas were hated by Malas. In 1995, in one of my earliest papers, I had stated that in India, no revolution was possible without annihilation of caste, and annihilation of caste was not possible without a revolution.

Since castes were skillfully consecrated in the Constitution for the purpose of providing social justice (read: reservations) for the majority of population (SC/ST/OBCs total over 75 per cent), the caste identities for others too have survived, alive in electoral games of political parties too.

The story succinctly points out the caste arithmetic of political parties on the eve of elections, and the play of money and muscle power. When there was a seemingly pro-communist atmosphere during the 1957 elections, Gidla describes how S.K. Patil was sent from Bombay to Andhra with tons of money to bribe people and intensify the foul propaganda against communists, and win over the middle-class intellectuals, such as teachers, lawyers, writers. It turned the tables. The communists eventually won only a handful of seats in the new legislature. This incident would repeat thereafter, in dozens of elections, and ultimately reduce the communists to a state of near non-entity.

Communists were supposed to understand the character of the state that the ruling classes had constructed with their pro-people rhetoric. Failing to do so, they inevitably followed ruling class stratagem to see people in terms of their castes and communities.

An insight into SM and Seetharamaiah

Gidla’s major contribution is the way she has presented Satyamurthy alias Satyam/SM. We didn’t know anything about SM, about his poverty-stricken university life, his struggles, his travails, his parasitic habits and his idiosyncrasies. Nobody knew about Kondapally Seetharamaiah either, before Gilda narrated his affair with the widow of a martyred comrade in Telangana, and how he deserted his own wife and children to live with the widow at a far off place.

In all these myriad details, she has kept her focus intact—on how caste operates in India. I have found that caste is defined only in relation to Dalits, for the rest it’s seen as innocuous information.

But Gidla could never escape her caste, even in America. When she meets a fellow Indian, it is often one of the first questions they ask. The shadow of caste does not cease to follow one even after migrating to distant lands.

In sum, it is an important book that must be read by all interested in knowing contemporary reality of India.

Dr. Anand Teltumbde is a Professor in Goa Institute of Management, Goa.

“I have found that caste is defined only in relation to Dalits, for the rest it’s seen as innocuous information.”

So caste is irrelevant for non-Dalits ? That means it’s already disappearing !