The book sparkles because of the material the author had access to and makes Husain a consumable superstar.

Ila Pal’s, “Husain Portrait of an Artist” claims to be an authentic picture of Husain but instead serves to further canonise Husain as the myth, the legend, the icon, and persona. The myth of the Artist and ‘creative genius’ is problematic because it perpetuates a culture of passive spectatorship. The much-venerated Husain saheb’s halo is fortunately punctuated and relieved, humanised and made veristic through his own letters and quotes and quips.

Though many compare Husain to Picasso, he is a Warhol-esque tour-de-force, who eventually reveled in playing into the popular imagination and documenting himself, very self-consciously, as the book reveals, by going so far as carbon-copying and cataloging his own letters. Such archives lend themselves to the making of a consumable superstar, and despite being the elaborate name-dropping exercise that it is, the book sparkles because of the material the author had access to.

The story spans many decades of the artist’s life, from the billboard school of art to fame and elaborate forays into filmmaking, sculpted in turn by each woman he loved, wrote letters and delectable poetry to. Each verse is a sheer delight.

The author draws together the themes of a paradoxical quest for love and freedom in Husain’s personal and artistic commitments (and calculated non-commitments). A passage by Geeta Kapur talks about how the painter indulges in contours but withdraws and flattens, basholi-style, the form. He indulges women but firmly refuses to be a “Majnoon” (disappointed, self-destroying lover). And maybe, it is in the curious striking of this mid-ground between form and formlessness, that he successfully synthesises a vast range of mythological and cultural influences andothers pertaining to art history– particularly, as the author elucidates, the dramatic quality of the Hindu ethos, and the powerful starkness of the Muslim austerity.

In chronicling Husain the lover, her own gaze is a glaring presence and contrasts too sharply with the lyrical affection that comes through the painters own words and feelings. She comes off as rather clingy and tabloid-like in parts. Her commentary on his various lovers notwithstanding, even the episode of his being admitted to a hospital in Delhi is chronicled through her diary entries, which though honest and full of the flavor of each day and moment, are sometimes tedious.

Of singular import are Pal’s interactions with Husain’s family – particularly his daughters, who talk simply and directly of their individual relationships with Husain, of their reckoning with his various emotional involvements with women, and his non-interfering yet fiercely supportive presence.

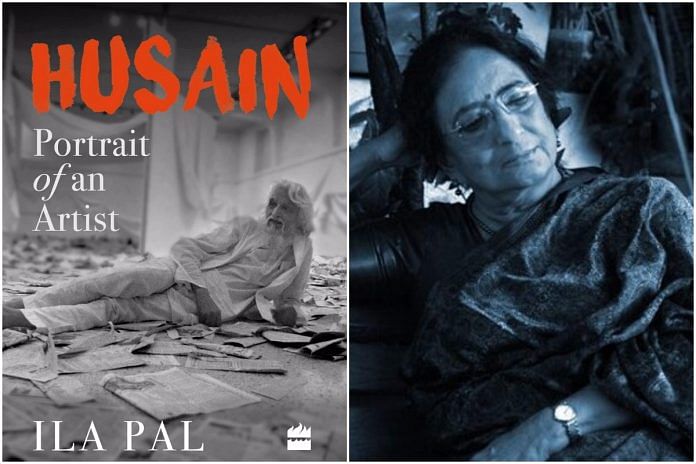

The book has colour photo spreads which feature reproductions of paintings, sketches, photographs, and doodles – some of which are hilariously delightful. The newspaper clippings covering the south Mumbai club controversy, where Husain was shown the door for being barefoot, are doubly so. This visual inclusion in the book really brings the painter’s journey, with all its magnificent and mundane quirks, alive.

The warm, humorous conversations with Husain that form the essence of the book reach truly touching proportions, fanned by the author’s use of hyperbole, in the chapters that relate Husain defying cancer and open-heart surgery. Regardless of the text reading like a succession of interviews, the visuals, architectural spaces, colors and symbols become characters and narrative experiences – an aesthetic experience akin to his films.

Though infamous for the contentions Husain courted, his works are an ode to the pluralistic, syncretic traditions that he emerged from. The author talks rather beautifully of his controversial sketch of Saraswati as, “an elegant white-on-black line drawing, which makes the viewer reflect on the old Indian tradition of ‘nirakara’ or formlessness, yet evoked anger rather than contemplation and appreciation”.

The author’s own nuanced appreciation of Husain’s work coupled with commentators like Anil Dharker who points out that, “his nudes are not nudes – the flesh tones and voluptuous curves that would be the essence of a nude are entirely absent”, signpost a way of grappling with Husain’s iconography. The reference point for images of Hindu Gods and Goddesses for the mass consciousness is still the lowest common denominator of Ravi Varma’s calendar art– a strictly colonial hangover.

And Husain’s figurative model challenges this imagery. While it may not be absolute, it is necessarily a part of the lineage of the rendered human form – a historically significant and multi-cultural artistic endeavor prevailing across Greek sculpture, the Byzantine Mosaics, Miniature paintings, the Ajanta caves, Warli paintings, and the Modern and Contemporary movements in India and the west. Its inclusion and acceptance into this vast and rich tradition would represent a very serious evolution of our visual and cultural vocabularies. And the book, as a rather comprehensive resurgence of Husain’s legacy, is noteworthy.

Namrata Chhabria is an artist and works works with a Delhi-based art gallery.

chadarmodh husain