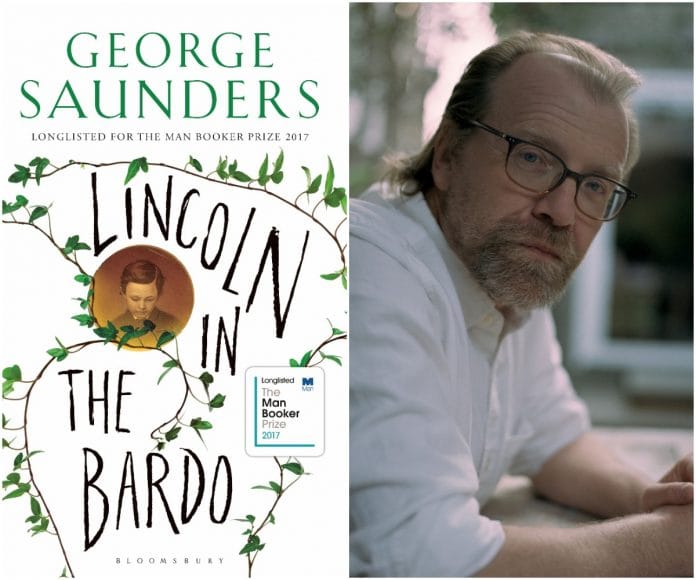

Saunder’s first novel is set in the Bardo— a liminal space between life and after-life where Abraham Lincoln visits his deceased young son

(Are you comforted?)

No.

(It is time.

To go.)

These lines form the backbone of George Saunders’ first novel, Lincoln in the Bardo (Random House, 2017), which is constructed around the story of a grieving President Abraham Lincoln visiting his young son’s crypt in the dead of the night.

The novel is set during the American Civil War, and explores the great personal tragedy of a father losing his beloved son, while war lingers in the background.

Saunders’ stage is borrowed from the Tibetan tradition: the Bardo, a transitional realm between the life and the after-life. His characters are mostly dead but unwilling to admit it, and are therefore content to be trapped as ghosts in the Bardo, all the while convinced that their condition is temporary.

It is in this liminal space that Saunders injects history into. Lincoln, apparently, was shattered when his son Willie Lincoln died at just eleven years of age, and visited his son’s crypt several times just to hold him. Saunders says that the image this brought to his mind was a “melding of the Lincoln Memorial and the Pietà”, and he certainly does that image justice.

Willie Lincoln finds himself in the Bardo, unable to comprehend what has happened to him, but steadfast in his belief that he should remain in the Bardo until his mother or his father come to get him. Sure enough, his father does appear, but in the flesh. At one point, one of the ghosts, describes Lincoln by saying “he might have been, in that moment, a sculpture on the theme of Loss.”

The narrative is driven by a dissonant chorus of these ghosts, all too afraid to move on to the after-life. The three main characters (besides Lincoln and his son) are a man who slit his wrists over his gay lover and immediately regretted it, a printer who died while on the verge of consummating his marriage with his young bride, and a self-aware reverend. All three take it upon themselves to help Willie Lincoln move on.

Ghosts who stay in the Bardo for a substantial amount of time begin to manifest their desires in their physical appearance, distorting their Dantean phantasms. Children have it worse: their already disfigured spectres would become permanently fused with their surroundings if they did not pass quickly.

What ensues can only be described as an ironic, macabre race against time in the afterlife. The narrative is interspersed with (some) primary, secondary and fictional accounts of the Lincolns’ lives, which humorously conflict with each other. Other ghosts add their voices to the chaotic din, each telling their own stories and lamenting their misfortunes, passing each day with “devastating sameness”. The ghosts include slave owners, unhappy mothers, bawdy drunks, and a few adult versions of Casper the Friendly Ghost.

The trajectory of the novel follows their reluctant but inevitable path to acceptance, and does so with grace, poignant insights and morbid humour. Despite the novel’s pandemonium, it very clearly explores the themes of loss and love using the non-corporeal characters as touchstones for Lincoln.

And if ever there is an image of melancholia, it is as Saunders describes it: a father, defeated and kneeling, holding his son’s body and weeping.