A new book titled ‘The RTI Story: Power to the People’ by Aruna Roy chronicles how the simple act of demanding minimum wages became a struggle for the ‘right to know’.

It is an unbearably worn-out cliché to say that history is written by victors. More important questions for memory scholars are how, why and when the history-writing and memorialisation efforts occur.

The new book titled ‘The RTI Story: Power to the People’ by Aruna Roy (Roli Books 2018) offers interesting insights into why the RTI movement needs to be chronicled in contemporary India. The effort to urgently historicise the movement relies on two factors: To ward off any attempt by urban intellectuals to hijack the story by reminding people of its rural roots; and to remobilise people against any pushback or dilution of the hard-fought RTI law.

In April 2015, thousands of RTI activists gathered in a small town called Beawar in Rajasthan to commemorate adharna (picket) held 19 years ago at a traffic roundabout called Chang Gate. They recalled the 40-day dharna out of which the campaign for a national RTI law began. Beawar is the RTI janmabhoomi and a small memorial was built there. The speeches included the dream of an RTI museum in Beawar. That is when the effort to memoralise began.

And now comes the new book – 13 years after the powerful, transformative and empowering national RTI Act was passed.

As it happens with the chronicling of any movement, the official memory is largely one of what the leaders said and did. But the book reminds readers that the RTI law was born in the poverty-stricken, drought-hit, corruption-ridden villages of Rajasthan. How did poor people — mostly manual, uneducated, landless workers — imagine and chart a path-breaking journey towards participatory governance, transparency and information-democracy?

At its heart, a stir for wages

During the 1996 dharna, the book says, “the people of Beawar were puzzled that poor villagers were not demanding essentials like food, wages or land but something as abstract as the Right to Information”.

This line goes into the heart of the book’s intent and argument. Rural workers in Rajasthan protested for minimum wages in the middle of bazaars, on cobbler’s platforms, the rural highways and at the collectorates.

And all their demands for minimum wages for their public-work labour boiled down to two words: ‘Muster rolls’. That held the information (often false) of how many labourers were engaged and paid. Gaining access to the tightly controlled muster rolls was key to exposing fraud and corruption in the public works department.

And that is how the simple act of demanding minimum wages became the struggle for the ‘right to know’.

The information in the official files contained stories of how pension funds, public-work wages, and funds for school buildings and hospitals were siphoned off — with fake vouchers and a fake list of beneficiaries.

The popular song in the RTI movement that the singer-activist Shankarji sang at almost every meeting in the 1990s encapsulates the fight to access official files: “Hamein nahin chahiye Uncle Chips, hamein nahin chahiye Pepsi cola, hamein chahiye photocopy.”

“When the poor ask for rights, they become victims of the system, sometimes with false cases against them. The system knew that information was power,” says the book.

A few pages later, the book quotes Mohanji, a Dalit farmer and bard: “Till we get those documents out, we will always be liars.”

These two lines define how the battle lines were drawn in the RTI movement.

The footsoldiers, the heroes

The protests morphed from dharnas and hunger strikes into the powerful and disruptive jan sunwayis (public hearings) where rural activists would read from the freshly obtained photocopy of an official document and the villagers would contest its content and corner the officials.

“The discrepancy between fact and government position — allegedly on the basis of records never made public — had to be stated or disclosed,” writes Roy.

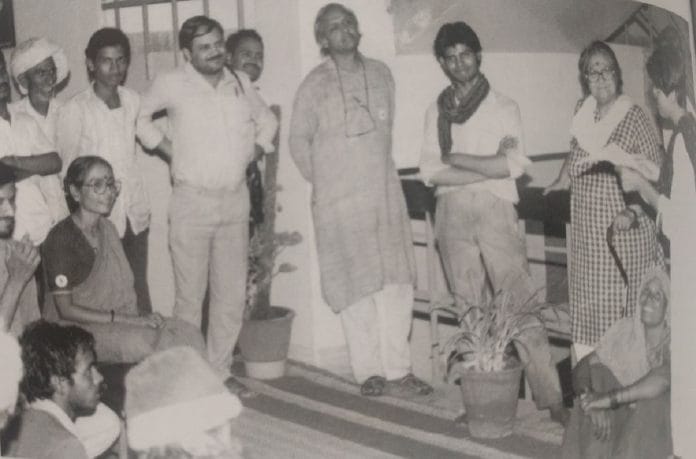

The book retraces these steps, quotes and celebrates the villagers and rural workers who participated in the early days of the movement, and also sources from the daily campaign diaries of Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS).

The Dalit bard who sang songs about corruption that went viral (in the pre-WhatsApp era) in villages, the villagers who barged into local block development offices and demanded a photocopy of muster rolls, rural storytellers who invoked allegorical tales to explain corruption and the opaque Official Secrets Act under the village tents; and a young IAS probationer who understood the meaning of transparency.

The footsoldiers of the movement were the real flag-bearers of democracy, says the book, and offers the readers a ‘story’ and an ‘exercise in building theory through practice’.

‘The RTI story: Power to the People by Aruna Roy’ has been published by Roli Books.