Turtles All The Way Down is cautious, careful, and apprehensive. At no point, however, does the novel romanticise mental illness.

We live in a time in which most millennials experience some form of social anxiety or stress, and it is important to remember that people do not choose to feel or think this way. Depression and suicide are commonplace occurrences, and self-diagnosis is often chosen over seeking professional help.

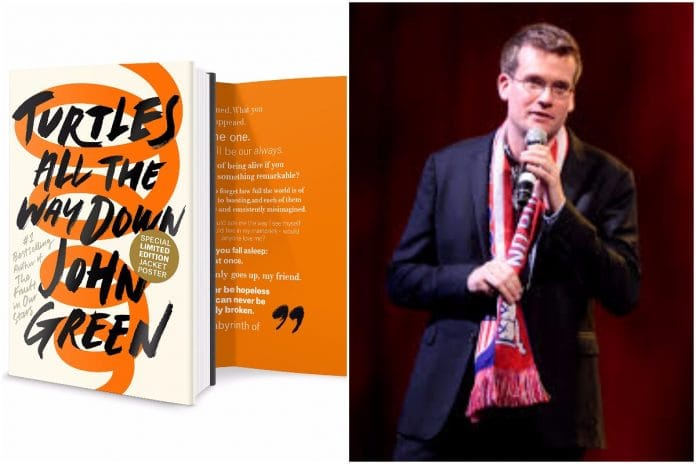

Quite possibly the coolest dorky YA writer, John Green has style. His books are quirky, have characters with interesting obsessions. There is always a best friend who is eccentric and an unsupervised adventure follows based on random, sketchy clues. Turtles All The Way Down is not that different.

It deals with the same themes of loss, disappearance, love, and growing up. It employs the same plot tropes, and is filled with the same obscure pop culture references. It’s what he’s known for. And with this novel, he doesn’t disappoint his familiar readers. But there’s a definite change in tone, a shift in gears. Turtles is, unbelievably so, atypical.

This novel is cautious, careful, and apprehensive — about falling in love, about growing up and experiencing life. It’s Green’s first novel after the hugely successful Fault in Our Stars. It took five years to write, and one can almost feel the time and thought that went into its creation weighing its pages down.

The story is told through the eyes Aza Holmes, a teenager struggling with anxiety and OCD. A billionaire has just gone missing, and Aza’s best friend Daisy is determined to find him and claim the $10,000 reward. This involves reconnecting with Aza’s old crush, who happens to be the billionaire’s son. Too much time is spent on this subplot, which is returned to after extended periods of time, making it awkward. It quickly becomes obvious that finding the billionaire isn’t the driving force behind the novel, and was a segue into Aza’s mind to initiate a conversation about mental illness.

Aza has OCD, and spends much of her time thinking about germs and infections. She goes to therapy to help her cope with her illnesses, and is incredibly self-aware, but finds herself unable to control her mind or her actions. To someone who has never been anxious or dealt with an overriding voice in your head telling you what to do, Aza’s internal monologue comes very close to the real thing. Her struggle is crippling, painfully so, which Green communicates so well that it leaves the reader frustrated and helpless too.

At one point, the characters are discussing how Molly in James Joyce’s Ulysses begs James, her writer, to let her out of the novel. (“O Jamesy! Let me up out of this,” she says.) Green uses this idea of a self-aware character begging the writer to be let out of its pages as a clever metaphor for mental illness itself. At your lowest points, you know that the darkest thoughts are your brain talking: and yet you think them anyway.

At no point, however, does the novel romanticise mental illness. It tries hard to tell the reader to not live just within their head, and reach out to anybody who might understand.

Aza has friends and family who love and trust her, but her own shame shackles her, and she spirals further and further into her “widening gyre”. (“Thought spirals” is what Aza uses to describe her repetitive thought processes.)

Green, too, has struggled with mental health issues and has poured that part of him into the novel. The story ends the same contemplative way it began, with a nondescript judgment. It’s just that this time, the ending has more resolve. We leave Aza just as we found her, except now she knows she will have to learn how to work on herself. Aza’s journey takes the reader along, making you feel that while you might not be cured, you will survive, and one day, like Aza, thrive.

in real life so many have ocd but nobody thinks parallel to illnesses but it’s a novel but a nobel beautified version of a writer