Searching for writings on the wall in this edition of state elections in Haryana, you’d be struck by what isn’t to be seen there. Or almost isn’t: the face and name of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Nor even promises from him. No Modi ki Guarantee, no Modi ka bharosa.

The party’s campaign tagline is, ‘Bharosa dil se, BJP phir se’ (Trust with your hearts, bring the BJP again). That’s a bit prosaic given the high standard the BJP sets for itself on coining slogans. Plus, it doesn’t rhyme. Or, as a gaggle of young karyakartas tell me on the sidelines of a modest rally in a banquet hall, “Tuk bhi nahin milti (It doesn’t even rhyme properly).”

The most striking discordant note on the walls, however, isn’t poetic, but visual. It isn’t as if Modi is entirely missing. It is just that his isn’t the lead picture in any of the party’s posters or campaign stationery. The lead picture in most cases is that of the candidate in a constituency. That’s close to the phenomenon we’d noted with Congress candidates in our WritingsOnTheWall piece from the 2014 assembly elections. The equation has reversed now, but in part. Because the Congress candidates then had completely dropped the Gandhis. Modi is still there, but just about.

In the top right corner, in slightly smaller size than the candidate’s picture, is the bearded face of Chief Minister Nayab Singh Saini, sworn in just a month before the general elections began in April as the party belatedly realised how unpopular its two-term chief minister, Manohar Lal Khattar, had become. Cheek by jowl with Saini is a face most of us won’t recognise. At least I didn’t. I’d also say in my defence that I asked a dozen people at BJP rallies and street processions and only rarely was somebody, usually a bit older, able to name this particular notable.

This is Mohan Lal Badoli, and who’s he? He is the party’s state chief, appointed in a belated attempt at damage control after the Lok Sabha setback, when the BJP lost five of the 10 Haryana seats. Among the losers was Badoli himself, from Sonipat. The only reason the loser was elevated was his caste: Brahmin.

Dare to get ahead of the Jats, they’ll make you pay

After two terms in power without needing to underline its loyal caste coalitions, the BJP is now back to the basics. Upper castes and Punjabis (many of them from families of Partition refugees) are its mainstay. They are also the most numerous along the Grand Trunk Road, where the most urbanised constituencies lie and where the BJP won most of its seats in the 2014 and 2019 assembly polls. This zone also has the smallest percentage of Jats, who the party has alienated.

For it to have any chance of winning a third term, or collecting enough seats to achieve a hung assembly in which to play, it must max out along the G.T. Road.

In the 2014 and 2019 elections, both for the Lok Sabha and the assembly, the BJP didn’t need to flaunt its caste base. It could take that for granted as long as two other factors worked. One, Hinduised nationalism and second, the name Narendra Modi. These were synonymous. This is why the BJP won a majority with 47 in a House of 90 in 2014. To understand why this was so dramatic, we need to note that until then, the highest the BJP had scored was 16 in 1987. Most of these were also urban seats along the G.T. Road.

It was the rise of Narendra Modi that won the BJP rural Haryana, especially its Jats. They might constitute only about 22 percent of the vote, but as you’d expect given their political and social domination, punch way above their weight. This metaphor is particularly apt in this land of contact sport: boxing and wrestling.

At some point, the BJP got ahead of itself and decided it could do without the Jats. In its first term, the community was sidelined. In the second, it was outsourced to coalition partner Dushyant Chautala, one of the great-grandsons of Devi Lal who broke away from jailed grandfather Om Prakash Chautala’s Indian National Lok Dal (INLD) to launch his own Jannayak Janta Party (JJP).

That move has bombed and the Jats, furious at this denial of pre-eminence, have moved to the Congress, especially its leader Bhupinder Singh Hooda. This showed in the 2024 Lok Sabha results as the BJP lost all the predominantly Jat/rural/Dalit seats but won most of the cities. Notably, it lost both the seats reserved for the Scheduled Castes. Rural Haryana, Jats and Dalits no longer seemed in Modi’s thrall.

Can we call this campaign Modi bachao, Modi jitao?

That the party is now acknowledging this is the campaign’s most important writing on the wall. On the banners where the candidate’s picture is the biggest and the chief minister and the party chief’s the next biggest, Modi’s is among the smallest. Not just that, he is just the first in a series of 10 tiny mugshots in the top left. I recognised the first four and the sixth, and with some effort the fifth. For the rest, I gave up and asked for help. If you were a candidate in the Haryana Civil Services examination and were asked to name the last six of these 10, you might flunk, too.

Let’s list them: Modi, party chief J.P. Nadda, former chief minister and now cabinet minister Manohar Lal Khattar, cabinet minister and Haryana election-in-charge Dharmendra Pradhan , former Tripura chief minister and Haryana election co-in-charge Biplab Deb, and the state in-charge, prominent Rajasthan leader Satish Poonia. For the remaining four, I needed the help of our senior associate editor and Haryana expert, Sushil Manav, but the names don’t matter.

One is a former Lok Sabha MP, not fielded this summer but he’s a Punjabi, the second a Rajya Sabha MP from across the Yamuna in UP, called in here to rally his Gujjar caste votes, the third is a functionary of the state Mahila Morcha, mostly unknown but a Baniya, and the fourth an equally nondescript district office-bearer of the BJP.

It is in this series of notables that Modi’s face, in his current favourite cap, features. In exactly the same size as all of them. Just the first among equals. It’s almost as if you want to protect Modi from any adverse outcome in this election, and yet want votes in his name. Shall we then suggest a name for this campaign: Modi bachao, Modi jitao (Shield Modi but make Modi win)?

All that was essential to Haryana politics but was superseded by the overwhelming power of Modi is now back: caste, dynasty and defection. Starting from 2003, this will be the fourth edition of WritingsOnTheWall from Haryana, and you can find them here. In the second, 2014, watching the burst of Modi-led aspiration and confidence, I had said that Haryana voters might have put identity behind them. As you should expect in what was India’s richest state with a population above 25 lakhs. That idea lasted exactly a decade. It has now ended with the relative fading of the Modi power.

The BJP appointed a Brahmin chief, and a recent loser at that, in a state where the caste counts for no more than 7.5 percent. A perhaps unprecedented 11 of its 90 candidates are Brahmins. Shore up your own if you can’t be sure of the others. Two small coalitions have come up, each including one of India’s most prominent Dalit leaders: Chandra Shekhar Azad with Dushyant Chautala and Mayawati with Dushyant’s uncle Abhay’s INLD. You might want to discount conspiracy theories, but any votes these tiny and unlikely Jat-Dalit coalitions pick up will be to the Congress’s cost. The fight now can be defined as between the BJP’s anti-Jat coalition-building and the Congress playing down the Jat domination that urban castes fear. Putting a benign, friendlier Hooda in front is critical to that.

Also Read: Education, aspiration & 3 de-hyphenations: A changing Kashmir votes and vents

Return and revenge of the dynasties & defectors

The storied dynasties of Haryana have had books and PhD theses written about them, and many obituaries over the past decade. Now they are all back. If I listed the names, it might take a thousand words. Let’s therefore round them off as nine from the Devi Lal dynasty across four parties/symbols (one almost also had the BJP ticket but then didn’t), and three each from Bansi Lal’s and Bhajan Lal’s across the BJP and the Congress. If you want to choose a burial ground for the BJP’s supposed revulsion of dynastic politics, it must be in Haryana. The one family/one position/ticket principle is also buried here with Arti Rao contesting from Ateli. Her father, Rao Inderjit Singh, is a Union minister of state and in turn the son of the late Ahir stalwart and once chief minister, Rao Birender Singh.

Haryana’s love of defection never quite died, but is now back in a manner unprecedented even in a state where a champion defector in late 1960s, Gaya Lal, gave us the Aaya Ram/Gaya Ram phenomenon. His son Udai Bhan, by the way, is the state Congress chief now.

Forget the prominent ones for now, like those from the three Lal dynasties who’ve been on a party merry-go-round. Check the walls in Panipat. The face you see most prolifically on the walls is that of an Independent. Rohita Rewri was a municipal councillor who won the Panipat City assembly seat for the BJP by a margin of 53,721 votes in 2014. Denied the ticket in 2019, her patience ran out and she defected to the Congress in May this year. Denied there as well, she quit and is now fighting as an Independent.

In 2019, Sanjay Agrawal lost the seat for the Congress to the BJP’s Parmod Vij by 39,545 votes. This time around, he defected to the BJP 72 hours before campaigning ended and extended support to its candidate, Vij. If this doesn’t make sense, check out the action last Thursday, a couple of hours before campaigning ended.

Young Ashok Tanwar, who Rahul Gandhi had talent-hunted as his Dalit star of the future and even made Haryana state chief at the mere age of 38, made a grand comeback to the Congress in Gandhi’s presence at a rally at 2.55 pm. At 2 pm, Tanwar had been speaking at a BJP rally seeking votes for its candidate instead. This is his fifth stop in a decade. He left the Congress to float his own party, then joined Mamata Banerjee’s Trinamool Congress, left it for the Aam Aadmi Party, went on to the BJP and is now back ‘home’ when the Congress looks resurgent. Devi Lal’s son Ranjit Singh joined the BJP a month before it contested the Lok Sabha elections, contested on its ticket and lost. Now denied a ticket for the assembly, he’s fighting as an Independent.

All this sounds messy, doesn’t it? That’s because the factor that provided a new centre of gravity to the state’s politics for a decade has faded. You can see it in the Writings on the Wall, the BJP portrait gallery, as also in the falling number of Modi’s rallies: four compared to 10 in 2014. For the BJP, it is still about winning in Modi’s name without saying so. De-risking or de-leveraging of this kind was never the BJP style since 2014. To that extent, Haryana is again a national trend-setter.

Finding childhood landmarks for what’s changed, and what hasn’t

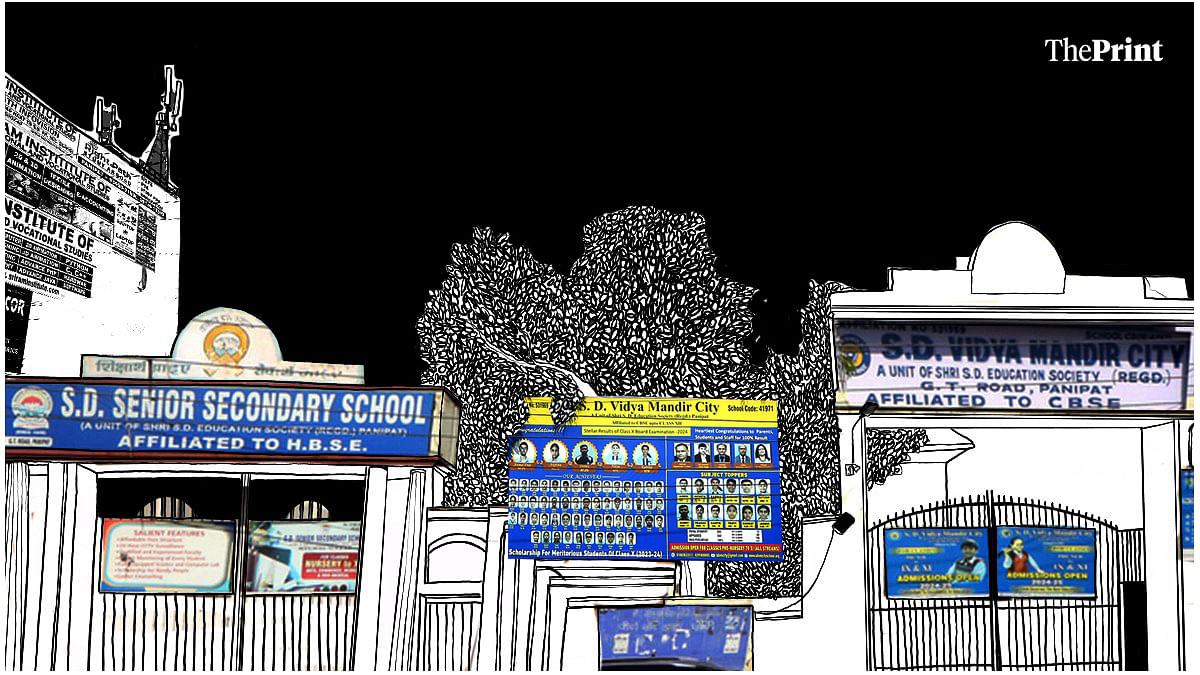

Any search for what’s changing and what isn’t in your home state must also include some childhood landmarks. For example, my high school in Panipat where I passed my Class 10, Sanatan Dharma Higher Secondary School on G.T. Road, is still there, frozen in time. It is still affiliated to the Haryana Board of School Education (HBSE), which gave me my matriculation certificate in 1971. This hasn’t changed, but there is change evident in the same frame.

The land next to the old school building, which we sometimes used as an informal playground, now has another school, like a sister to the original, albeit a more pampered one. This one is affiliated to the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) which, with English medium, is what those with less modest means would prefer. The large board between the two schools flaunts a gallery of meritorious students and toppers, all from the CBSE version, of course.

This is change and continuity all in the same space, the old school providing education as a minimal need and the new one to fuel aspiration. A class system scripted in the same writing on the wall.

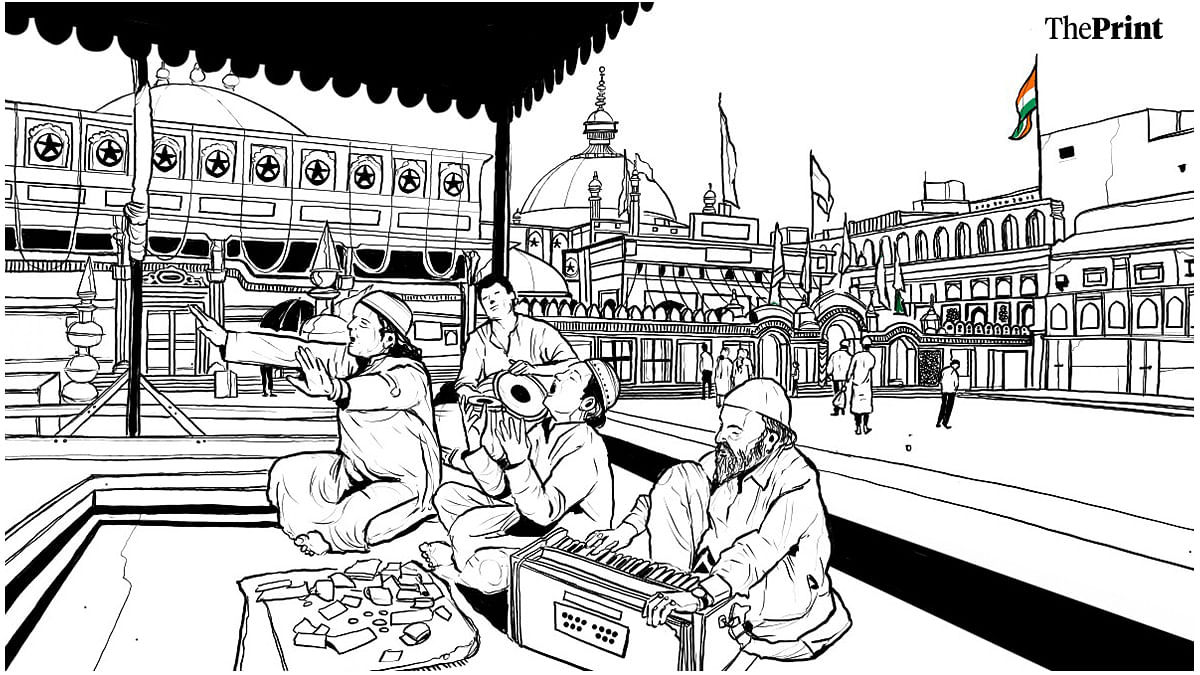

In the chaotic years of schooling more than five decades ago, it was easy to bunk classes and loiter into what was a quaint old quarter of the city. A bit deep inside sits the beautiful, 725-year-old dargah of Sufi saint Bu-Ali Qalandar, a descendant of the more famous Shahbaz Qalandar of ‘mast-mast’ fame.

I find people from all faiths still here to tie wishing threads, and then spot something I wouldn’t have figured about 55 years ago. The tomb of poet Altaf Hussain Hali, or just Hali, a contemporary of Mirza Ghalib’s. Hali was born in Panipat in 1837 and lies buried in the dargah precincts.

A qawwali is on at the dargah as always, but change is evident at the imposing ancient entrance. A tricolour on the top. It’s a writing on the wall for the times.

And arguably the most famous loser in our history

Who’s the most famous loser in Indian history? The list could be long and the argument contentious. Many would say Siraj-ud-Daula to the British at Plassey. But nobody can compete with the three losers at the battles of Panipat, 235 years apart. It became the battlefield repeatedly as the reigning power in Delhi brought its armies to these flat lands along the western bank of the Yamuna to stop an invader from the west.

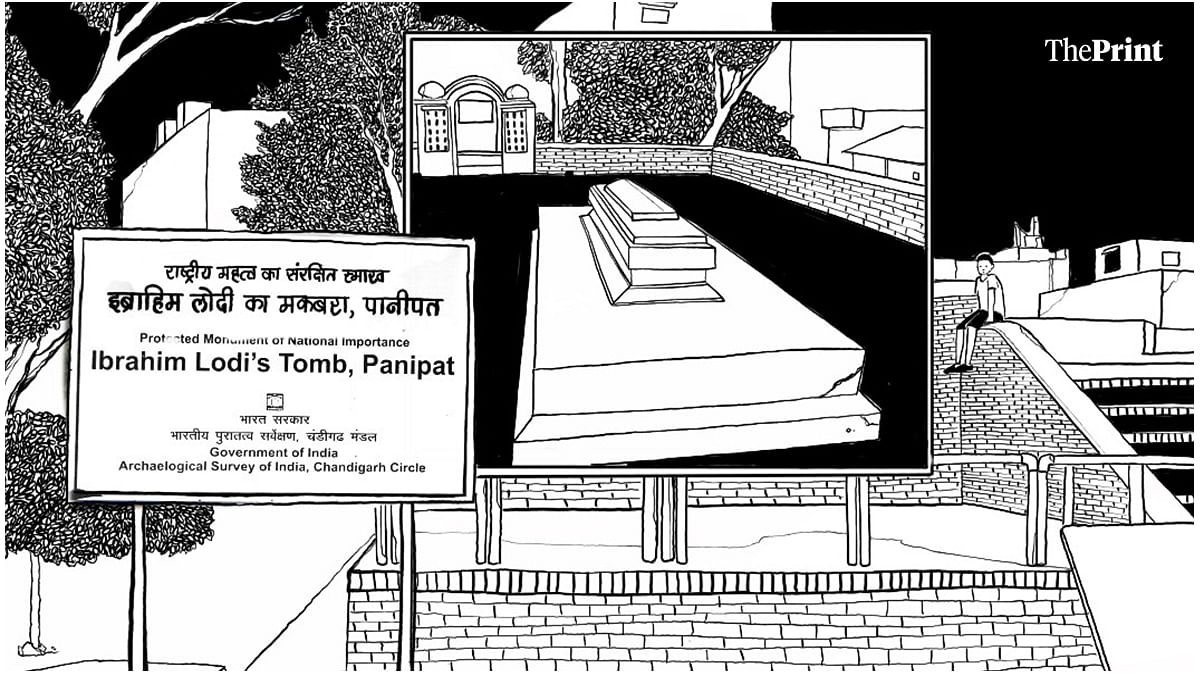

Of the three losers here, I’d argue Ibrahim Lodi is the most significant. Babur vanquished him in the First Battle of Panipat in 1526, ended the sultans and founded the Mughal Dynasty.

His grave, on an uncovered brick platform, in what was then a mostly empty stretch far from the city and abutting G.T.Road, was also a loitering spot for us urchins. There was always an Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) board proclaiming that it had been a protected monument since 1919.

A search for it now took more than an hour. Nobody knew there was a man called Ibrahim Lodi or that such a tomb existed. As it turns out, the city has grown around it. The grave only survives because a tiny park with children’s swings has been laid out around it. Google lists it and takes you to the front of the park. But where’s the tomb?

We stood in front of the park and asked the owners of shops facing it if they knew where Ibrahim Lodi’s tomb was, and they said they didn’t. Still following the old instinct, we looked around and found the mostly hidden signboard. The park, such as it is, would have outraged the Lodis, who created the magnificent one in New Delhi. It has garbage, clumps of gamblers and drug pushers, a broken metal sculpture of two bearded soldiers in armour and the model of an ancient cannon with one half of the barrel lost and the other collapsed. Whether it represents the victors or the losers, we don’t know. Right now, it’s the sculpture that’s getting lost.

A scrawny young Sikh with a sparse open beard figures that we are journalists. “You media people can do something to save this place,” he says. “Nobody has seen a tourist here. All it draws is junkies and on school days, ‘nabalig’ (juvenile) kids searching for some privacy.” I am of course translating in great understatement.

“You call this a protected monument?” he asks. I strain to read the faded ASI stone saying, ‘Here lies Ibrahim Lodi’ etc. Elements have erased the paint. This writing on the wall is stark: Nobody cares for a loser from 500 years ago. Even if he’s our history’s most consequential loser.

Also Read: Yogi’s cows, Modi’s houses, Akhilesh’s jobs: Why this is a more ‘normal’ Uttar Pradesh election

A stunning reversal of fortune.