The outcome of the Bihar assembly election is unprecedented in several ways. The Nitish Kumar-led NDA (BJP-89, JDU-85, LJP-19, HAM-5, RLM-4) won 202 seats, but the Tejashwi Yadav-led INDIA (RJD-25, Congress-6, CPL (ML)- 2, CPM (1), IIP-1) alliance managed only 35 seats. Asaduddin Owaisi’s AIMIM has won 5 seats, and the BSP has won 1 seat. It was a historical election and needs critical examination. We need to ask why the opposition’s employment-focused campaign failed.

Lalu Prasad Yadav’s Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD), once a prominent representative of Mandal politics, now finds itself in a political era where welfare, good governance, and new aspirations are overshadowing old caste equations. The party has failed to build a broad social coalition to bring together extremely backward and non-Yadav backward castes. This reflects the weak grasp of the RJD on the ongoing social changes in the state, where a large voter base has increasingly gravitated toward Nitish Kumar and the BJP.

Yadav dominance

Once a powerful symbol of backward class unity, RJD’s politics nowadays creates suspicion and unease among EBCs. They no longer want to see any caste or community in power that carries an image of anarchy and insecurity. In this context, the RJD’s core support base, the Yadavs, is facing a sense of rejection among other social groups. Many marginalised communities have closely experienced Yadav dominance in villages, panchayats, and local power structures. The growing dominance of Yadavs in administrative access, panchayat-level conflicts, resource control, and social prestige has further increased concerns.

Tejashwi Yadav tried to change this image by emphasising education, employment, and development. He could not erase their perception. In contrast, Nitish Kumar is seen as a more stable, secure, and reliable administrator. RJD’s claim of social justice often clashes with people’s actual need for social security.

The party requires the support of EBCs, women, and Dalits to win elections. For them, security’ and ‘respect’ are the top priorities. Social justice does not just mean political representation; it also means everyday security, equality at the local level, and respect for their voices and interests. They also need confidence that no community will dominate them in the name of political power. The RJD has failed to do that, and it is visible in its candidate nomination.

The party nominated the majority of its candidates from the Yadav community. It fielded candidates on a total of 143 seats, 53 of whom were from the Yadav community. Category-wise, the party allocated approximately 51 per cent of tickets to backward castes, nearly double their total population. This imbalance conveys a message: RJD is hesitant to provide equal representation and power-sharing to broader social groups.

The RJD allocated only 11 per cent of the tickets to EBCs, who make up 36 per cent of the Bihar population. In contrast, the Yadavs alone received over 37 per cent of the tickets. This didn’t contribute to the creation of a new social base. In fact, this was the first election held after a caste-based survey.

The party was expected to provide comprehensive representation to the EBCs, and it failed. Compared to the last assembly election, the number of tickets allotted to the EBCs was further reduced by 2 per cent. This was done at a time when the party’s weakest alliance is with the EBCs’ vote bank. The RJD’s predicament is twofold. On the one hand, it wants to expand its alliance without losing its traditional base of Yadav and Muslim voters. On the other hand, it wants the votes of the EBCs, neither giving them adequate representation nor assuring them that they will be relieved of Yadav dominance. This contradiction has further deepened the suspicion of the party among the EBCs.

Also read: In Bihar, BJP is courting upper castes—a clear shift from its 2020 strategy

Fraction with the INDIA bloc

Internal contradictions within the Grand Alliance also weakened the RJD’s overall strength. The Congress party’s consistently weak performance and uncertainty over seat-sharing slowed down the alliance’s entire election campaign. It also failed to present a clear, unified message or shared ideological foundation to counter the BJP-JD(U)’s “double-engine” model.

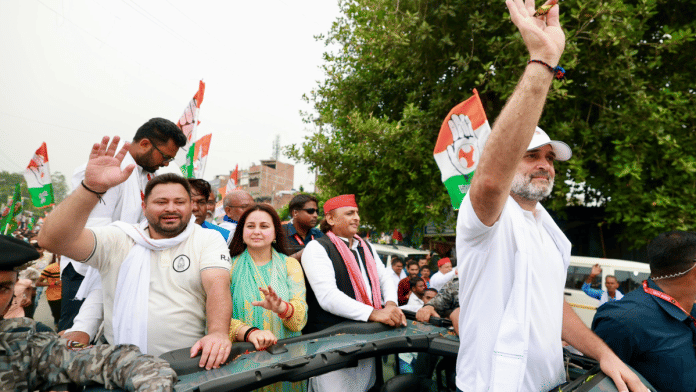

Congress continued to create unnecessary media hype around its ‘Vote Adhikar Yatra’, which lacked a strong social base. The party also lacks state leadership to strengthen its organisation. RJD excessively relied on Congress, which proved to be detrimental. Distancing itself from the Vote Adhikar Yatra, if the RJD had launched a separate public relations campaign on its own issues, its performance would not have been so poor. The crowd at this yatra was of the RJD, but it was presented as a Congress achievement on social media. This created arm-twisting in the ticket distribution, declaration of chief ministerial candidates, and reluctance to declare deputy chief minister. The Grand Alliance exhibited mismanagement at several levels, which impacted the voters.

The RJD’s inability to correct the social equation in the candidate nomination process, along with indecisiveness over seat-sharing, candidate nomination, and frequent agenda switching, created confusion among the voters. So, they went for the stable leader who has provided them security through good governance.

Arvind Kumar is a visiting lecturer in politics & international relations at the University of Hertfordshire and an associate fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London. He tweets @arvind_kumar__Pankaj Kumar is a PhD Scholar at Jamia Millia Islamia. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)