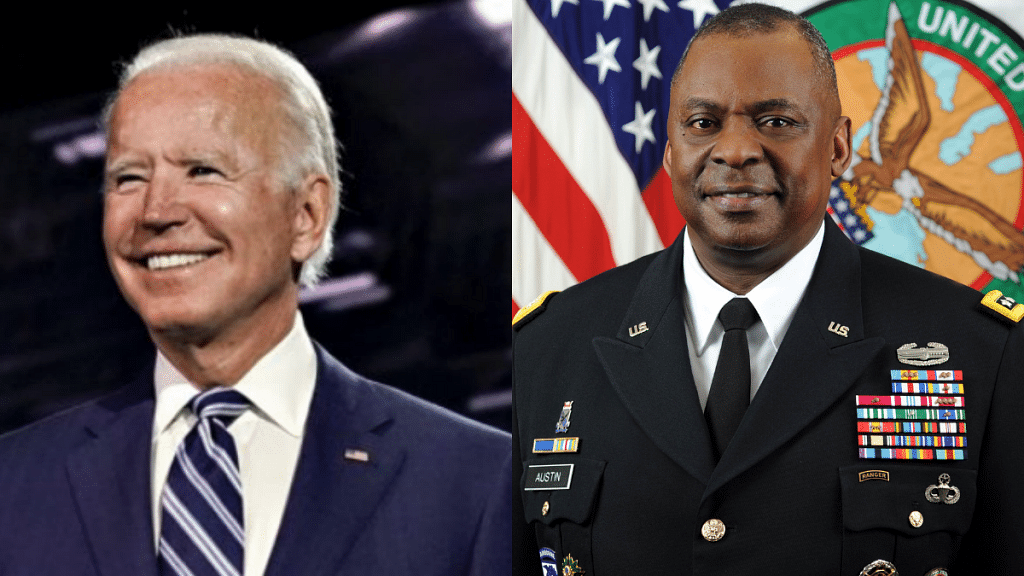

US President-elect Joe Biden’s choice of Lloyd Austin, an Army general who headed the US Central Command, as the Secretary of Defense has raised concerns about the Democrat’s foreign policy, especially towards the Indo-Pacific and China. For a number of reasons, these concerns are overblown. The state of US-China relations probably depend more on China than the US, but even more so on the underlying conditions of international politics and the balance of power in the region. While not inevitable, the overwhelming likelihood is of conflict between the US and China, irrespective of who the US Defense Secretary is, or indeed, who the US President is.

The cabinet choices of incoming US administrations are always tricky because they have to cater to different groups that make up the coalition that claim to have helped win the election as well as different groups that the new administration will need to depend on for future domestic political fights. This dynamic is particularly important with Biden because his was a fairly narrow victory, in which he squeaked through with margins of a few thousand votes in three critical states, Arizona, Georgia and Wisconsin. Illustratively, in each of these states, the third-placed Libertarian party won more votes than the margin. While Biden has a significant lead in total votes cast nationally, this is a meaningless number in the context of the US presidential election.

Even more importantly, Biden could be the first Democratic Party president elected without controlling both houses of Congress since 1885. This will be decided by the two run-off Senate elections in Georgia, slated for early January. If the Democrats lose even one of these, Republicans will have a clear majority in the Senate. This will be a critical obstacle to Biden, especially since it is the Senate that approves presidential appointments. But even if the Democrats win both, there are continuing internal differences between various factions in the party. Indeed, Biden may have picked Austin partly as a consequence of opposition from the Left-wing of the Democrats to Michèle Flournoy, who was initially considered the front-runner for the post. Moreover, Biden had repeatedly promised ‘a cabinet that looked like America’, which is not easy considering the demands from different groups. Biden’s justification for picking Austin, which itself is an indictment of the internal disagreements about the choice, emphasised that the US Army general “will be the first African American to helm the Defense Department”.

Also read: Iraq troop withdrawal was Austin’s failure — and Biden’s

A choice with a reason

While Biden’s choice is understandable because of these pressures, foreign policy analysts have pointed to Austin’s lack of familiarity with China and the Indo-Pacific, the looming security challenge that the US faces. China was not even mentioned in Biden’s justification for Austin’s selection. These concerns are growing because, in addition to not mentioning China, both Biden and Austin used the older term ‘Asia Pacific’ instead of the more recent formulation, ‘Indo-Pacific’. It harks to the possibility that a Biden administration might seek a new compact with China. This fits with the views of what Thomas Wright, a close observer of US foreign policy trends, has characterised as ‘the restorationists’ wing of Democratic foreign policy thinking. Biden picking John Kerry for a newly created cabinet position as a ‘climate envoy’ may be another indication of the ascendancy of the restorationists.

Still, the concerns about the Biden administration’s China policy may be overblown. For one, Biden clearly sees some of these appointments as a sop to the Left-wing within the Democratic coalition, and it may not be an indicator that Biden will seek an accommodation with China. More importantly, even if Biden were so inclined, it is not entirely his choice to make. Whether there will be a deepening conflict between the US and China is also dependent on Beijing’s choices. China has been the driver of the increasingly tense international condition, with its harsh ‘wolf-warrior diplomacy’, its hostage-taking, and its use of trade to coerce other countries near and far. None of this is a defensive response to the conditions that China faces but an offensive tendency that has many roots. One is China’s growing power. As countries become stronger, the areas and issues they consider as vital to their national security also expand. China is no different.

Also read: Biden backs Black general for defence secretary but will need waiver of civilian control rule

China’s game too

In China’s case, however, this natural expansion of interest is exacerbated by the hyper-nationalism that the Chinese regime has fostered, an inclination that makes the country emotionally brittle and defensive when there is no need to be and thus prone to picking unnecessary fights. In addition, there is a strategic-cultural element that makes China think it is a civilisational State to which smaller neighbours must kowtow. Add to the mix Xi Jinping’s own messianic view of China’s and his place in history. Much of this is already baked into the situation and there is little that Biden can do about it, making the likelihood of a conflictual US-China relations rather difficult to avoid, short of a dramatic change within China itself.

It is, of course, understandable that Biden might want to focus on the many domestic problems that the US faces, including its economy. But what is equally true is that no great power has willingly relinquished leadership because leadership brings with it benefits that far outweigh the costs. Biden is likely to want to further push US allies and partners on burden-sharing. This is something that President Donald Trump did haphazardly but it has been a long-standing issue in the US’ relations with its partners. But to expect that Biden will do more than that will require an unlikely American exceptionalism in great power politics.

The author is a professor in International Politics at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi. Views are personal.