When a general leads from the front in a losing battle, and then ultimately loses, you have to wonder: was it courage or foolhardiness?

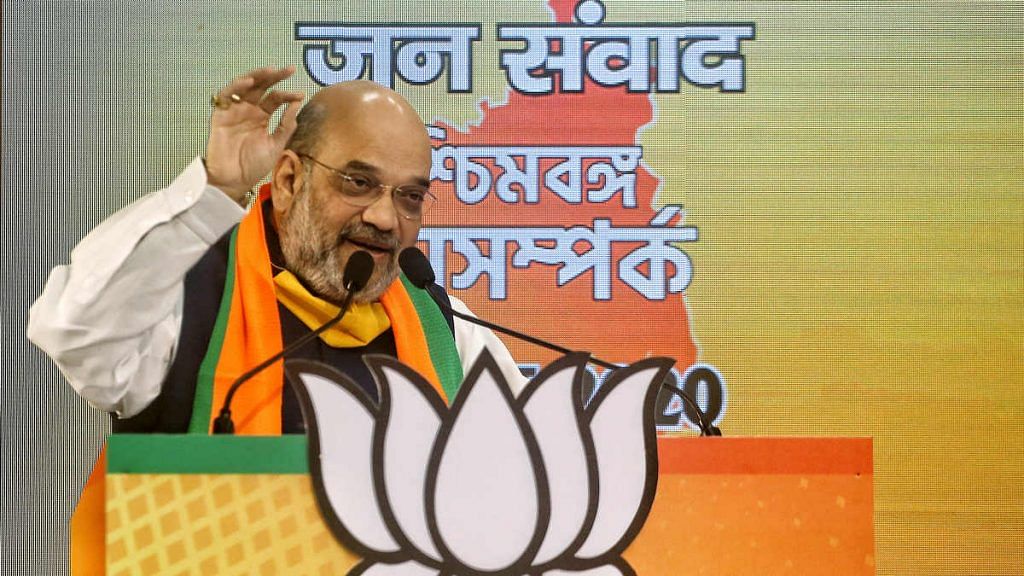

Given the number of elections Amit Shah has lost, the establishment media actually does him a disservice by exaggerating his image as a ‘Chanakya’, a ‘master strategist’, the invincible and much-feared Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) leader before whom the best of politicians fail.

Even before the Narendra Modi government had completed a year in power, Modi and Shah suffered a humiliating defeat in the national capital in 2015, winning only 3 of the 70 seats in the Delhi assembly election. The rest 67 went to an upstart Aam Aadmi Party (AAP). Shah camped three months in Patna for the Bihar assembly election later that year, and lost to old fogeys Lalu Yadav and Nitish Kumar who came together with a former Modi aide, Prashant Kishor, as their strategist.

Amit Shah wasn’t able to form a BJP government in Karnataka after the election in 2018 despite having the weakest party as his opponent, the Congress. Under Shah’s watch, the BJP lost Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh – the last two states being those where the party was once considered as unshakeable as in Gujarat. And it came perilously close to losing Gujarat. It lost Jharkhand and Haryana, forming a coalition government in the latter. It lost Maharashtra despite winning with the pre-poll coalition and it lost Delhi again in 2020. Shah took on Ahmed Patel to steal a Rajya Sabha seat in a prestige battle in Gujarat — and lost.

Also read: Too little democracy is why India’s reforms and progress are stymied

Fighting losing battles

Amit Shah can of course take these defeats on the chin because he has much larger victories he can claim, the biggest one being 303 seats in the 2019 Lok Sabha election, held while he was still the BJP president. Even if you give all the credit to Modi for that election, some credit will automatically go to Shah as Modi’s foremost political colleague.

Yet Amit Shah doesn’t have to lead from the front and undermine his image as the invincible Chanakya. He takes these temporary blows to his image. In the Delhi assembly election in February 2020, Shah went around campaigning in street corners. The result was an embarrassing 8 of 70 seats in the election.

Similarly, Amit Shah recently campaigned in the municipal election in Hyderabad, increasing the party’s seats from 4 to 48 but nevertheless still losing in the 150-member council.

Shah surely knew the party stood no chance of winning the Rajasthan assembly election in December 2018 with an unpopular Vasundhara Raje Scindia but he still campaigned in the state, spending several days there. Modi did some rallies too, but the Prime Minister sometimes reduces his exposure in states where the party thinks it may have a tough time. You can count the number of rallies and tell when Modi is exerting himself in an election and when he’s not. In Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh in 2018, there wasn’t so much Modi. In West Bengal today, it is Modi-Modi. The risks are calculated.

Also read: The unspoken words that help Modi retain public approval

The next three elections

For Amit Shah, every risk seems to be worth putting his name to. A home minister recently recovered from a long bout of illness, Shah was there putting his face out for a municipal election in Hyderabad.

What’s the political, electoral logic behind this?

It has to do with his age. He is 56, 14 years junior to Narendra Modi. It is obvious as daylight that Amit Shah sees himself as Modi’s successor to the PM’s post. When Shah gives it all to winning even a municipal seat, he is investing in his future, as also that of his party. This is also partly why, in this writer’s estimation, he put his weight behind Yogi Adityanath to make him Uttar Pradesh chief minister. Adityanath is 8 years younger than Shah, and will be the best possible Hindutva mascot when Shah ‘moderates’ his image to go more mainstream the way Modi did in 2014. This is also why the BJP has made sure its district presidents are in their 40s, just like Adityanath. It is an investment in the future, for the next 20 years or so. That’s also why Shah handpicked Tejasvi Surya as the BJP’s youth face.

The electoral logic isn’t new. It was famously articulated by Kanshi Ram, founder of the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP). Kanshi Ram said the BSP fought the first election to lose, the second one to defeat and the third one to win. This is the strategy Yogendra Yadav wanted Arvind Kejriwal to follow, but Kejriwal did not want to become a small player in every state, instead preferring to put all his eggs in the Punjab basket. Having burnt his hands in Punjab, he’s now taking to the same strategy, and is planning to fight several state assembly elections hereon.

The idea is that in every successive election, the party must increase its vote-share. Therefore, what’s worse than losing an election is to lose vote-share. The vote-share in terms of the sheer percentage of votes must go up every election, at the very least be stable, and certainly not be allowed to fall.

For this reason, parties with long-term imagination fight every election to win, give their 100 per cent to every single election, even when they know in the heart of hearts that they are going to lose the imminent election. This is also why politics is a job that needs one’s full effort 24x7x365, because power must be used to expand power every single day.

When Amit Shah is fighting an election, he’s also thinking of the next three-four election cycles. Not every election is like Tripura, which the BJP won in just one cycle. Just look at how many election cycles the BJP is taking to invest in Odisha, West Bengal, Bihar, and all the southern states, inching closer each time, even if it takes decades.

Amit Shah’s presence on the frontlines of an election may or may not influence voters, but it is crucial in charging up party workers who then campaign harder to persuade every voter.

Also read: The method in the madness of ‘jhatka’ policymaking

A, B+, B, C

Today this philosophy is so ingrained in the BJP workers that they’ll tell you the way they’ve been taught. The BJP divides seats as A, B+, B and C, a party worker had explained to me in Gujarat in the 2017 assembly election there. ‘A’ seats are those which the party mostly wins anyway, what the media calls strongholds. C seats are those which the party is unlikely to win — strongholds of other parties. B seats are those where the party has a strong vote-share but hasn’t been winning. And B+ are those where the party lost marginally.

“We work to take C to B, B to B+, and B+ to A,” this worker told me.

That’s what Amit Shah just did in Hyderabad’s municipal elections, he took the BJP from C to B.

These calculations are made right up to the booth level, and each kind of seat gets its own strategy. Booth-level electoral behaviour is known because the Election Commission releases something called Form 20, where it reveals how many people voted for which candidate in which seat. This data from past few elections is crunched to figure out which booths, no matter what, always vote for the BJP, which ones don’t, and which ones happily change preferences from election to election. These swing booths, like swing seats, get the maximum effort and attention.

Also read: In Congress after Ahmed Patel, Rahul Gandhi needs to play the bigger person, call for unity

Defending the fort

Amit Shah led a Hindutva-centric campaign for the BJP in the Delhi assembly election in 2020, knowing that the AAP was winning, to enthuse party workers to not give up and work to retain the vote-share. Once a traditional BJP voter votes for another party and another symbol (in this case, the AAP’s broom), you risk losing their loyalty in the long run.

This is also how the BSP thinks, which is why it is so averse to pre-poll alliances, with the exception of the 2019 Lok Sabha election. Parties that think long-run don’t want their core voters to vote for another symbol — ever.

When you are losing an election, it becomes important to not lose too badly because if your vote-share erodes by a lot, you won’t be taken seriously in the next election. That’s why Amit Shah is happy to lose some battles to win the larger war.

Rahul Gandhi and the Congress party, by contrast, seem to run away from elections they think they are likely to lose. Many opposition leaders don’t give their best to elections because they see no hope of winning them. If they’d learn from Amit Shah, they’d know how important it is to fight losing battles with all you have.

Shivam Vij is a contributing editor at ThePrint. Views are personal.