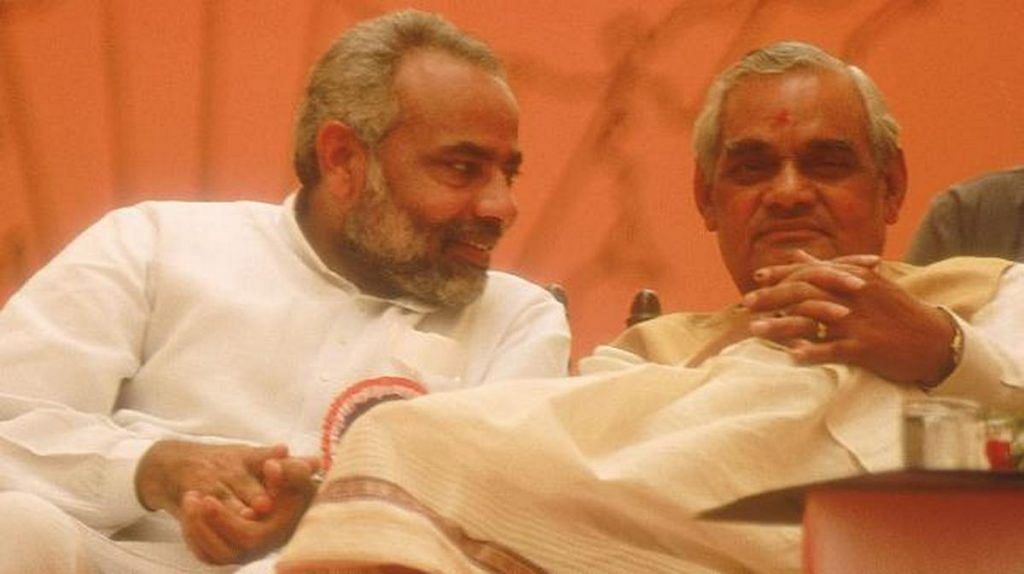

In India’s 2004 general election, then-Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee looked invincible. The media and the pollsters alike agreed that he would come back. for another term. The defeat of Vajpayee’s Bharatiya Janata Party-led National Democratic Alliance came as a surprise.

Now, Modi critics think something similar can happen in 2019 too.

Today, the rural economy is facing a slowdown similar to the one witnessed around the 2004 election. Given the alarming reports of rising unemployment and the overall economic slowdown, how could there not be a strong anti-incumbency sentiment, people wonder. Perhaps, there’s an under-current demanding change of government in the Hindi hinterland that media and pollsters are unable to catch.

Yet, there’s a lot today that is different from 2004.

Also read: Unlike Vajpayee & Manmohan, PM Modi thinks prudence in conflict is a self-imposed fetter

1. PM-KISAN: Going against his self-avowed ideology of ‘empowerment over entitlement’, the Narendra Modi government came up with a last-minute cash handout. The PM-KISAN scheme has already given Rs 2,000 to many farmers across India, and promises another two instalments of the same amount by the rest of the financial year. The money is targeted at small farmers with less than up to 2-hectare land — they are often also the swing voters Modi has been targeting, the lower OBCs.

2. Rurban India: India is no longer as rural as it was in 2004. It is more urban than what the 2011 Census figures show. There’s been the rise of the ‘rurban’ — places that aren’t quite city and not quite village either. For a lot of rural Indians, farming is increasingly becoming only one of the many sources of income. It is thus important to not over-read farm distress, which is anyway concentrated in regions and is crop-specific. The political distance between village and city has also been shortened by new roads, cable TV and smartphones.

3. Balakot strikes: The military tensions with Pakistan in February have not made the 2019 Lok Sabha pollsa ‘war’ election. Pakistan and terrorism are not, even in the BJP’s own pitch before the voters, the top election issue. But the Balakot strikes helped Modi made this a ‘national’ election, countering the opposition’s attempt to localise the election and reduce the Modi factor. When the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) lost in 2004, Arun Jaitley said in an interview that caste and regional sentiments had overtaken the national pro-Vajpayee sentiment. In 2019, the Balakot strikes have reminded voters that defence, for instance, is a national issue they should care about.

4. Modi is not saying ‘India Shining’: Modi and his party are not saying ‘India Shining’. Many including L.K. Advani had felt that that slogan backfired. The Congress party’s counter-slogan was ‘Aam aadmi ko kya mila? (What did the common man get?)’

Modi has been clever to avoid the India Shining trap. His main pitch is not that he has made India great. On the contrary, he’s been toning down expectations: ‘Modi hai to mumkin hai’ (Modi makes things possible). From the promise of good days, Modi is now saying he’s just made things possible. From the tall promises of 2014, we are now being told that Modi is just a watchman – a chowkidar.

This has been a part of Modi’s strategy to postpone desire — it’s coming, it’s coming, he always says. He rarely says it’s over, India’s Shining, please clap.

“I have never said that I have completed all the work. The ones who ran the govt for 70 years couldn’t fulfil their promises, how can I do that in just five years?” he said recently. In short, he is avoiding the ‘India Shining’ trap.

Also read: To be relevant in 2019, Congress must rewind to 1996-2004

5. New battlefields: The BJP’s seats in Bihar came down from 23 in 1999 to five in 2004. In UP, they came down from 29 to 10. The BJP got the maximum possible seats in the Hindi heartland states in 2014. The BJP understands that it would be impossible to repeat 71 seats in UPor win every single seat in Rajasthan and Gujarat in 2019.

That is why, unlike Vajpayee, it has sought to shift the main battlefield from UP to Bengal and Odisha. Its big push in the two eastern states could help it offset at least some of its losses in the Hindi heartland. Even before that happens, this is helping the BJP project its ‘winnability’ — the all-important perception to grab the pole position.

6. Travelling light with allies: It is not just the BJP that lost seats in 2004, its allies let it down as well. The Telugu Desam Party in what was then undivided Andhra Pradesh came down from 29 seats in 1999 to just five seats in 2004. In 2019, the BJP doesn’t have many big allies. Of the ones it does have, only the Akali Dal is expected to do badly. Modi cleverly let go of TDP’s Chandrababu Naidu when he demanded special status for his state. Modi thus has the option open to ally with Jagan Mohan Reddy and KCR. A light pre-poll coalition means Modi will have greater leg room to choose from the winners, if need be.

7. No big riot: It is debatable whether the 2002 Gujarat pogrom led to the BJP’s defeat in the 2004 general election, but Vajpayee himself felt they did. Presuming he was right, for whatever reasons, it is noteworthy that there hasn’t been large-scale communal violence of the Gujarat 2002-kind.

There’s another way to look at this. The BJP lost 25 per cent of its seat tally in 2004. If that percentage is repeated, then the BJP will come down from 282 to about 212. That would still put the party in the pole position to form a coalition.

Also read: Modi’s 2019 mantra: Forget achhe din, fear terror, Pakistan, Muslim