With such a high proportion of late deciders who could be swayed during the campaign, political parties and their leaders cannot afford to take their foot off the pedal before the polling day.

Do campaigns matter in determining electoral outcomes in India? If elections in India were all about the caste arithmetic, anti-incumbency and the popularity of leaders, then political parties would not be spending so much energy on campaigns.

After all the perception of the incumbent’s rule and the leaders’ popularity does not change drastically in the 14 days before polling. And caste combinations largely remain frozen, for such group-based loyalties are built over a long period of time. Then, why did Prime Minister Modi address 21 rallies in Karnataka in a span of two weeks? Why were Sonia Gandhi, despite her poor health, and H.D. Deve Gowda, in his mid-eighties, on the ground and mobilising votes for their parties?

The reason is fairly straightforward – last-minute voters decide the fate of electoral outcomes in India; especially in close elections like the one in Karnataka is this time. Survey evidence bears testimony to this claim.

The reason is fairly straightforward – last-minute voters decide the fate of electoral outcomes in India; especially in close elections like the one in Karnataka is this time. Survey evidence bears testimony to this claim.

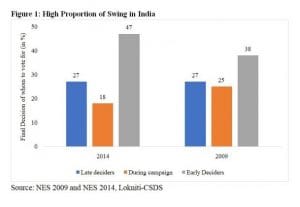

According to data collected by Lokniti-CSDS, in the 2014 and 2009 Lok Sabha elections, one in every four voters decided whom to vote for within 48 hours of polling day (See Figure 1). In Karnataka, the proportion of late deciders was higher than the national figure. With such a high proportion of late deciders who could be swayed during the campaign, political parties and their leaders cannot afford to take their foot off the pedal before the polling day.

Who are these late deciders and who do they vote for?

These late deciders come from all communities, though there are two types of such voters: One comprises those who wait for more information that can help them make their decision; while the other category includes those who are more strategic and want to be on the winning side. How do they know who is winning? This information-gathering exercise happens with only one question across the length and breadth of this country: “Is baar kiski hawa hai (Whom does the wave favour this time)?”.

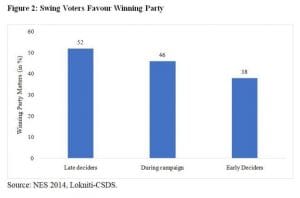

In India, late deciders vote overwhelmingly for the party perceived to be winning. In the National Election Survey (NES) 2014, voters were asked whether they voted for a party because they thought it was going to win, or if winnability was not part of their decision matrix. The data presented in Figure 2 clearly shows that more than half of the late deciders favour the party perceived to be winning. In 2014, the BJP led the Congress by eight percentage points among voters who had made their decision even before the campaign started, but it almost doubled its lead (i.e. 16 percentage points) among those who decided in the last 48 hours.

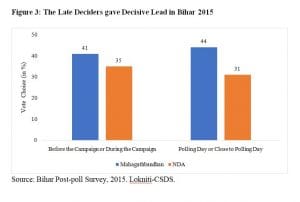

This phenomenon of late deciders titling the balance in favour of the winning party was visible during the 2015 Bihar elections as well (See Figure 3). A comparison of the pre- and post-poll surveys from Bihar showed a late surge in favour of the Mahagathbandhan (MGB), with a fairly large proportion of voters (26 per cent) finally making up their mind in the last 48 hours.The MGB had an advantage even among the early deciders (non-swing voters), but the late deciders (swing voters) seemed to have given them a decisive lead over the NDA.

Similarly, during the Gujarat assembly election last year, intensive rallying by Modi with all sorts of appeals towards the end of the campaign made a difference for the BJP in what could have turned out to be a very close election. The BJP led by 15 percentage points among late deciders while it had trailed by two points among those who had decided prior to campaigning.

Who swings the late deciders? Leaders with a huge mass appeal can enthuse such late deciders to turn out and vote for their party. In addition to a popular leader, a sophisticated party machinery can identify these voters and convince them to vote for their party’s candidate in their respective constituencies. There is no doubt that nationally, at the moment, the Congress is far behind the BJP on these counts. Can the Gandhis manage to pull these voters towards the Congress? Has Siddaramaiah created a machinery to reach out to these voters in far-flung areas of Karnataka? We have our doubts.

The writers are PhD scholars in political science at University of California at Berkeley, US.