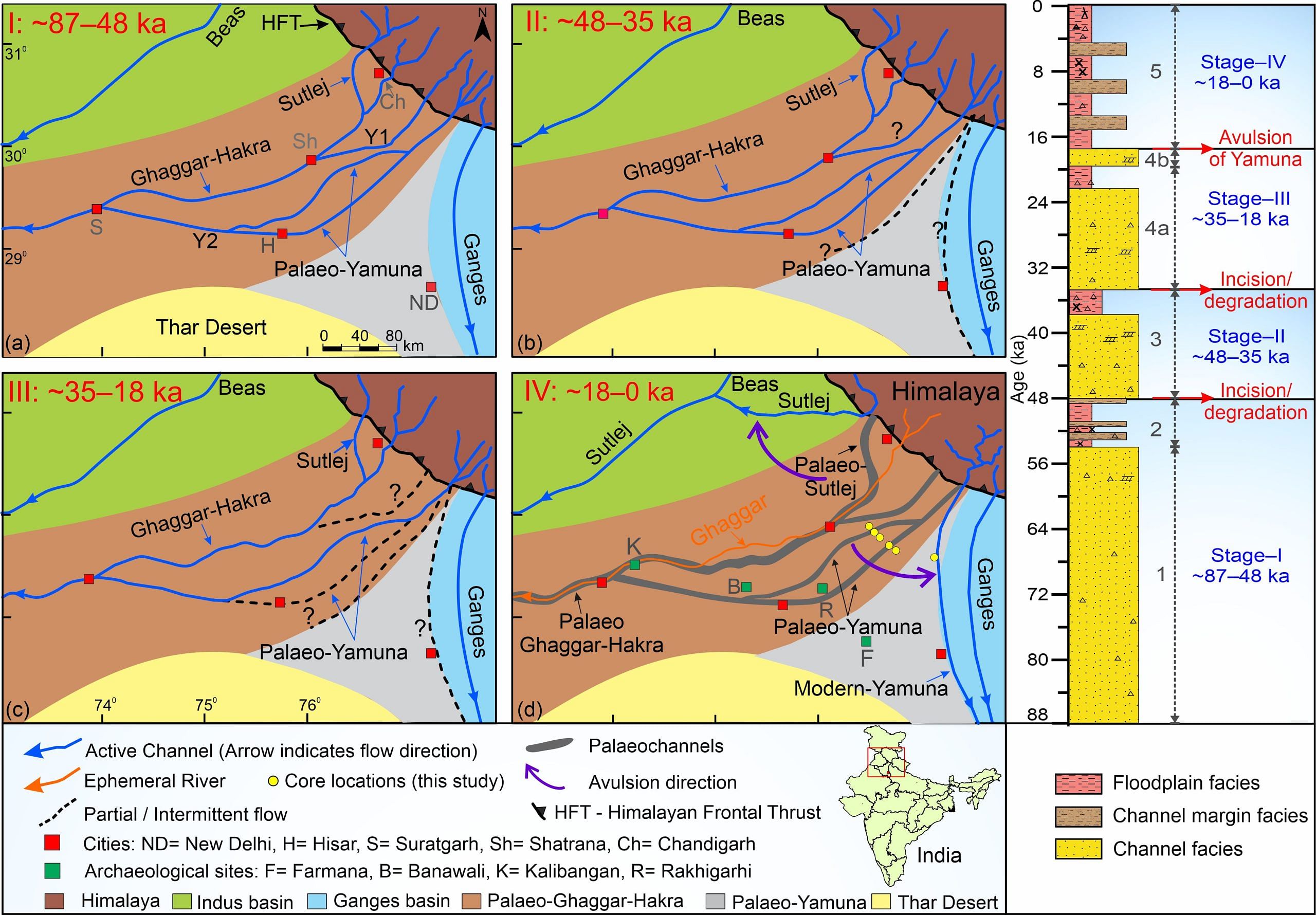

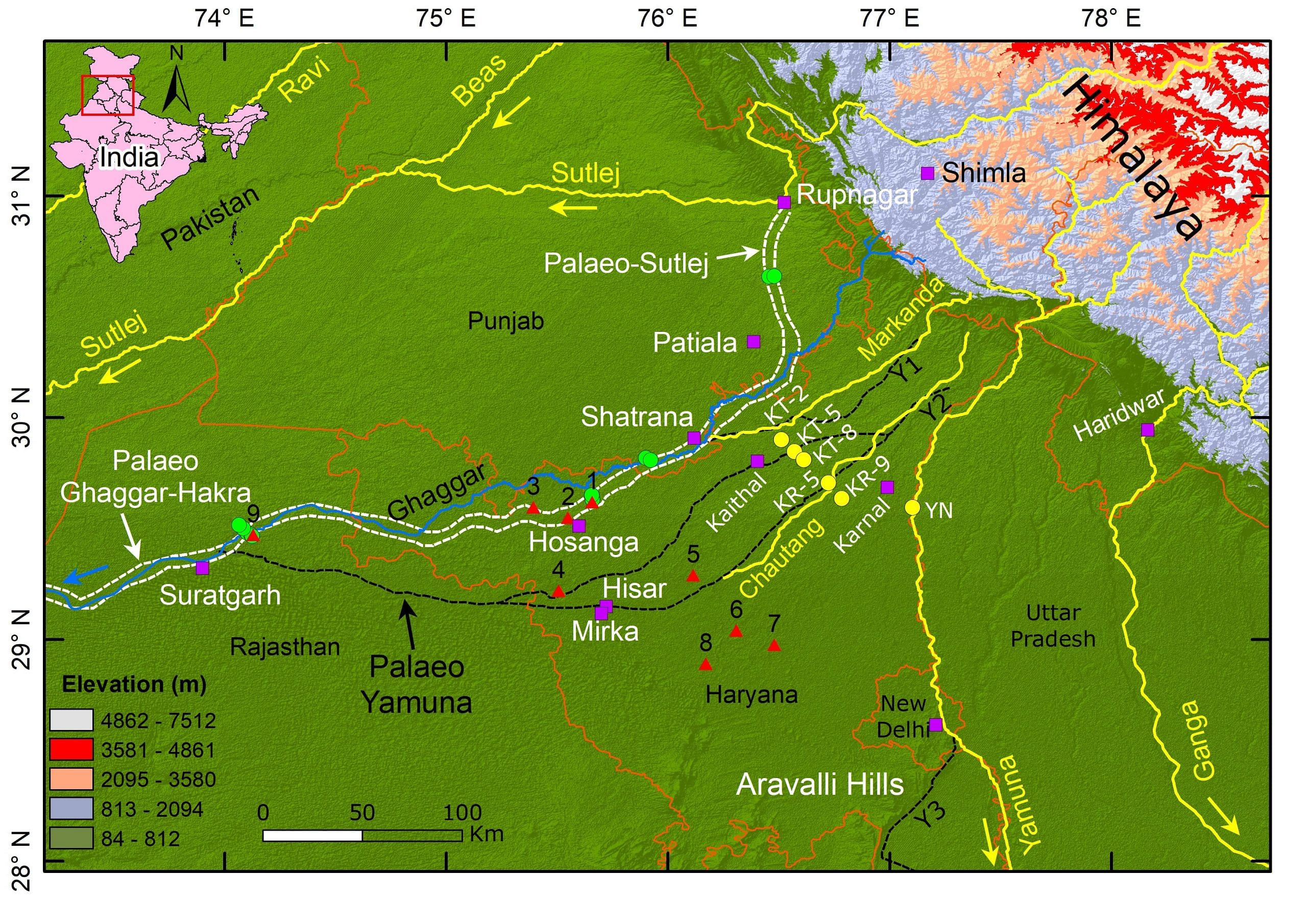

A recent study by researchers from IIT Kanpur and the Technical University of Denmark shed light on the evolution of the Yamuna River’s landscape. They analysed 47 Optically Stimulated Luminescence, or OSL, ages from six cores collected from the river’s old, abandoned channels, known as palaeochannels. The study suggested that the Yamuna River, which once met the Ghaggar-Hakra River near Suratgarh in Sri Ganganagar district of Rajasthan, shifted eastwards toward its current bed around 18,000 years ago, 12,000 years before the rise of the Harappan culture in the area.

Another study undertaken by Ajit Singh and team revealed that the Sutlej River moved westward, disconnecting from the Ghaggar-Hakra river system around 8,000 years ago (c.6000 BCE), coinciding with the beginning of farming practices in the region.

These groundbreaking studies suggest that Yamuna and Sutlej — which were the primary feeders of the Ghaggar-Hakra River — migrated away from the river system much before the emergence of the Harappan culture in the region. This questions the assumed role of the river in the rise and fall of the Harappan civilisation and previous assumptions about the contemporaneity of the Harappan civilisation and large river systems.

If the Yamuna moved eastward as early as 18,000 years ago and the Sutlej moved westward around 8,000 years ago, then by the time urbanisation started around 2600 BCE, the Ghaggar-Hakra was already a non-perennial river. The study also implies that the decline of the civilisation was influenced by a complex interplay of environmental and geological factors, including tectonic activity, rather than the presence or absence of any single river, thus questioning ‘river culture’ hypothesis.

Also read: Calling Harappan Civilisation ‘Vedic Saraswati’ is extreme—learn to hold a trowel first

Breaking the ‘river culture’ hypothesis

In one of his publications about his explorations in the Ghaggar Basin in 1950-52, archaeologist Amalananda Ghosh stated that “Harappan culture was mainly a riverine culture,” implying that the Harappan culture on the banks of the Indus and the Ghaggar-Hakra River was not only aided by the rivers for subsistence (fishing, agriculture, etc.), but was also birthed by them. In other words, river banks provided conducive conditions for survival and, of course, abundant water supply throughout the year. At least in the early years of sedentary life and agriculture-based economies, the river was the most important facilitator of culture.

Similarly, in the case of the Ghaggar-Hakra River, Harappan settlements flourished, which supported the river culture hypothesis. So, when the culture started to disintegrate and urban settlements on the river banks — like Kalibangan, Rakhigarhi, Binjor, and Banawali — were deserted around 2000/1900 BCE, archaeologists assumed that it was due to the collapse of the Ghaggar-Hakra (Saraswati) river system owing to a tectonic shift that disconnected the Sutlej and Yamuna rivers.

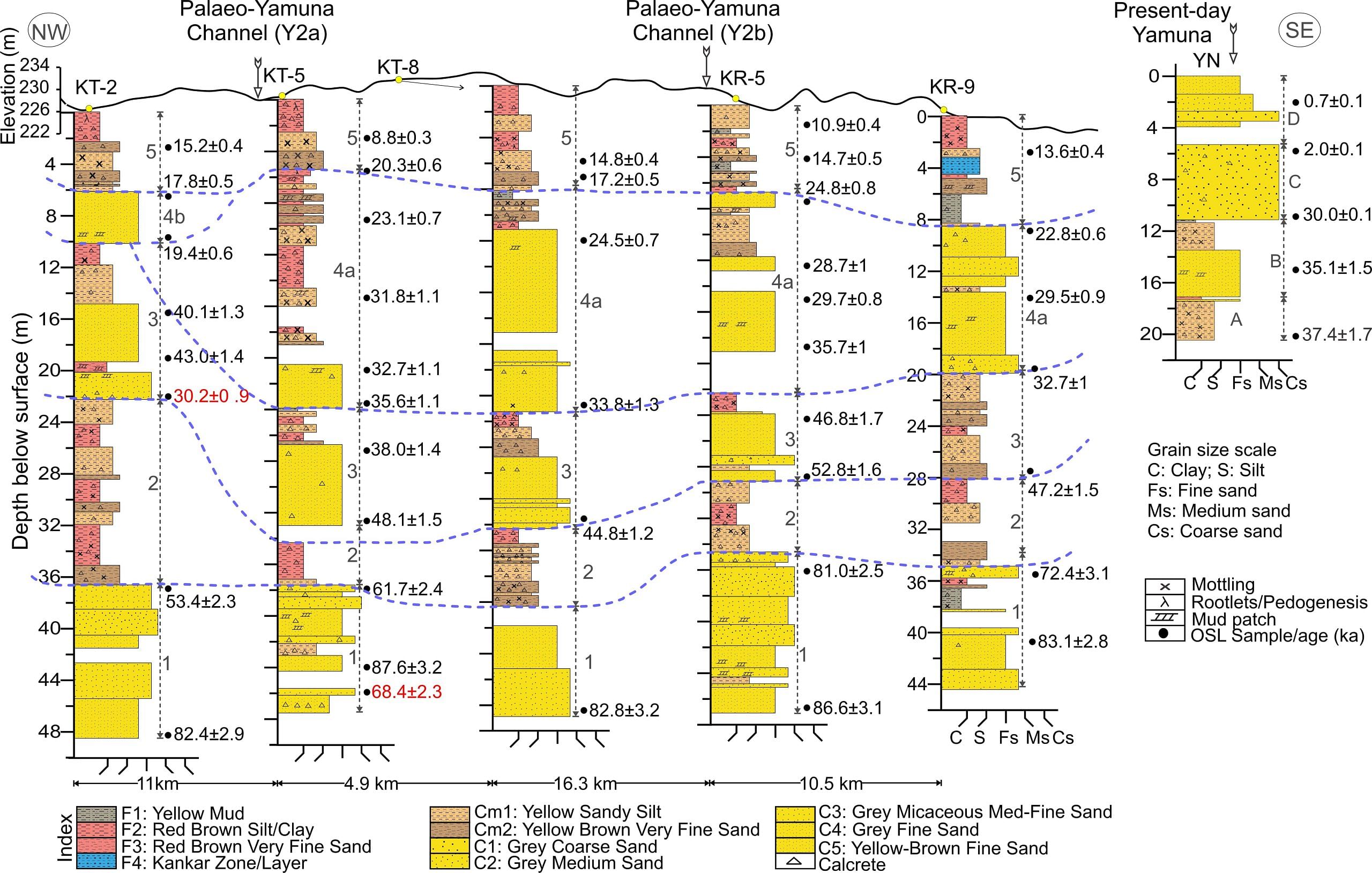

For a long period, in the absence of dates for these disconnections, such hypotheses retained their validity until Imran Khan, who did his doctoral research work on this topic under the supervision of Prof Rajiv Sinha (IIT Kanpur), along with his colleagues, took up the study. According to Khan, there were likely four possible stages of drainage reorganisation, culminating in a major eastward shift of the palaeo-Yamuna River around 18,000 years ago.

The study examines the geoarchaeological implications of these findings, challenging the prevailing theories about the role of rivers in sustaining ancient civilisations. The de-urbanisation of the Harappans was consistent with the Holocene aridification at 4.2 ka (kilo annum or thousand years), indicating that societal transformation may have been influenced by climate change. However, a contrasting view is that changing subsistence policies by changing crop patterns might be the primary root cause of the Harappan’s fall rather than climate change.

The deposition of very fine silt and mud between 18,000 and 9,000 years ago likely corresponds to the monsoon-fed ephemeral river system in the palaeo-Yamuna fan system (Haryana). This observation is in line with the findings of a previous work by Singh et al (2017) published in Nature Communications, which suggested that “it was the departure of the river, rather than its arrival, that triggered the growth of Indus urban settlements” in north-west India.

Also read: Painted Grey Ware from Bareilly holds the key to the question: Did India have a ‘dark age’?

Archaeological implications?

Though this groundbreaking research has provided a comprehensive understanding of the ancient river systems in the Northwestern Himalayan region and reaffirmed the non-contemporaneity of the Harappan civilisation with a large river system, the archaeological understanding of the Harappan civilisation, particularly of the settlements on the dried bed of the Ghaggar-Hakra River and the decline of the civilisation, now requires re-evaluation.

It was always believed that the decline of the culture on the banks of the Ghaggar-Hakra River was triggered by the changes in the hydraulic system; we are now met with evidence that proves otherwise. Early settlers and their Harappan descendants must have learnt to survive with a non-perennial river, and must have developed a water-management system like in the case of Dholavira in Kutch. This also stresses a lot of emphasis now on understanding palaeo-climate/environment as the monsoon must have played a very important role in agricultural practices and subsistence.

One perplexing question is regarding river transportation, which is thought to have facilitated internal trade. This also alters our understanding of the landscape during and after the Harappan period. This urges archaeologists to re-evaluate data to understand the settlement pattern of the early cultures, along with their subsistence pattern in the light of this study in order to write the story of human past in relation to its landscape – just like the geoscientists did with this study.

Disha Ahluwalia is an archaeologist and junior research fellow at the Indian Council Of Historical Research. She tweets @ahluwaliadisha. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)

It is nice study. But groundbreaking is not. We already shown the main points in Clift et al. and Giosan et al. both in 2012. This work confirms that.