In the aftermath of Donald Trump’s election as President of the United States, many Left-of-Centre American commentators seem to be in a daze. As with his first election, there are shrill cries of democracy being in danger, of institutions at risk—all rather ironic to us in the rest of the world, where autocracies and weakened institutions have been greatly assisted by American social media. Americans might be puzzled as to why an autocratic strongman holds such appeal with voters. But it’s a story India has seen a thousand times in our ancient and medieval politics, to say nothing of more recent times.

India’s earliest ‘republics’

While “democracy” as we know it—involving the suffrage of all adult citizens—is extremely recent, collective rule, where power was diffused among many, has existed in South Asia for over 2,000 years, possibly more. The Harappan Civilisation does not seem to have been monarchical, as it lacked the monumental royal temples and tombs of other Bronze Age cultures like Egypt and Mesopotamia. And the early Vedas suggest that tribal councils exerted substantial sway over Indo-Aryan chiefs. Either way, the clearest evidence of collective rule in South Asia dates to the very beginning of states in the Gangetic Plains. This took place after centuries of immigration, agricultural expansion and cultural mixing, dating to roughly the 7th century BCE.

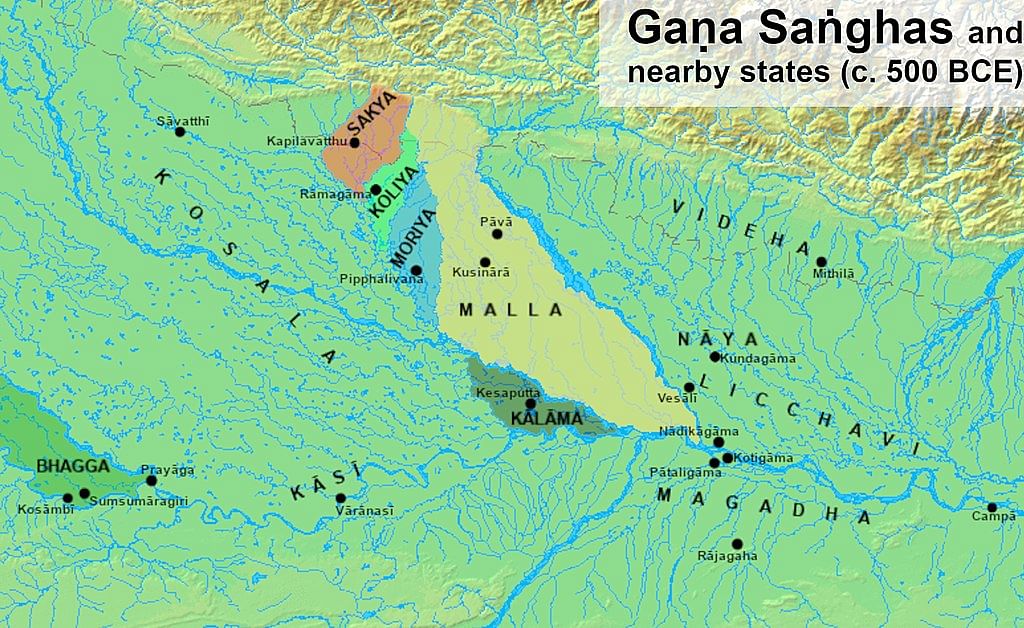

The territorial units of the Gangetic Plains were called janapadas, literally “where the people have put their feet”. There were two different state systems among the janapadas, both deriving from the rituals and kinship systems of the Indo-Aryans. In the first type, power grew concentrated in a single royal family of the Kshatriya caste, led by a raja. We’ll call them autocracies. In the second, power was diffused among many related Kshatriya landholders, who met periodically to enact rituals and take decisions. These states were known as gana-rajyas. Today they are sometimes called “democracies” or “republics”, to support the claim that the Republic of India is the “mother of democracy”. Considering that they were run solely by warrior aristocrats, “oligarchies” would be a better term, but let’s stick with “republics” for simplicity.

In the 7th and 6th centuries BCE, it was by no means evident which state system would emerge to dominate the Gangetic Plains. Autocracies and republics of various sizes jostled with each other. Through conquest, assimilation, and confederation, little janapadas became massive Maha-janapadas. Kosala, around present-day Ayodhya, was a major Maha-janapada autocracy. But to its east were two Maha-janapada republics: the Vrijjis around present-day Vaishali, and the Mallas around present-day Kushinagar. Both were composed of many smaller republics. The Vrijjis were particularly successful. At Vaishali, their major urban and ceremonial centre, they conducted rituals around a sacred tank annually and set out for war. They conquered the weak neighbouring kingdom of Videha and forcibly reorganised it into a republic like their own.

Also read: Torture, death, fines — how Arthashastra guided ancient kings on addressing crime & dissent

The end of oligarchies

The Buddha, arguably the single most influential figure in early India, was born to a Kshatriya lineage in the Shakya republic. He lived in the 5th century BCE when the balance between Gangetic autocracies and republics was fatally disrupted by a major new power: Magadha, in the southern portion of present-day Bihar.

To the other Maha-janapadas, Magadha was a bit of a parvenu, at the easternmost end of the Gangetic Plains, far from the early Indo-Aryan and Vedic centres such as Hastinapura, famed in the Mahabharata. But Magadha possessed something that the other Maha-janapadas did not: the Chhotanagpur Plateau, with its mineral riches and dense forests full of elephants. Its capital, Rajagriha (present-day Rajgir) was surrounded by fortified hills. It was a military autocracy, with capable rulers who deployed resources efficiently and recruited effective officers. Through smart marriage alliances, Magadha nudged its way west, where the other Maha-janapadas were concentrated, and took control of the present-day Benares region. Then its elephant corps marched east and conquered the port of Champa. Alarmed, the other Maha-janapadas rallied to stop it.

The main reason for Magadha’s success was that it was led by an extraordinary (and infamous) autocrat: Ajatashatru, a man who in his own time inspired lurid legends of patricide and sexual obsession, many of them related by Buddhist monks. This probably comes from the swirl of negative opinions generated by his military aggression toward the central Ganga basin, which, according to Buddhist legend, was resisted by nine Licchavi oligarchies confederated with the Vrijjis; nine Malla oligarchies, and 18 smaller oligarchies around present-day Benares. That’s no less than 36 different groups, all with their own histories and traditions, enmities and fears, all joined to resist the autocrat.

The Arthashastra of Kautilya, composed centuries later, compiled historical memories of Gangetic statehood and state formation and has an entire section (Book 11) on how autocrats destroyed republics. “Secret agents,” it says, “should find out the grounds for mutual abuse, hatred, enmity and quarrels among members, and sow dissension in anyone whose confidence they have gradually won, saying ‘That person defames you.’… Agents posing as teachers should provoke quarrels among their young boys… They should instigate princelings enjoying inferior luxuries with the prospect of superior luxuries.” Once the republic lost its internal cohesion, the autocrat could provide arms to one side and have them seize control. Astonishingly, nearly 2,000 years later, it seems that contemporary democracies have the exact same faultlines—and that the autocrat’s playbook has not changed very much. Dissension and division, polarisation, and instigating reckless young men, sometimes with genuine grievances and anger, but more often not.

The contradictions of autocracy

The ideal king of the Arthashastra might also reflect Ajatashatru himself: a hungry, ruthless empire-builder to whom nothing was off-limits, who had absolute command of his kingdom’s resources, paranoid in keeping himself alive, but generous to those loyal to him. But ancient Indian autocracies had their own problems: Once the Vrijji confederacy was conquered, Magadha simply had to lurch onto the next conquest to keep its elites happy. It was easy to incapacitate a republic by sowing division, but it was easier to incapacitate an autocracy. If its ruler was not capable, which rulers rarely are, his courtiers would run amok and enrich themselves—while using autocratic institutions to evade justice. And, sure enough, that’s exactly what happened to Magadha. After Ajatashatru shattered the great Gangetic republics, drawing other strongmen to him, he died. The strongmen all turned on each other to seize the throne, trying to expand the Magadha empire, assassinating each other. The cycle only ended centuries later, when the remarkable Ashoka Maurya declared an end to Gangetic conquests—only for his empire to collapse immediately after his death.

Republics left a deep cultural mark in the Gangetic Plains. Many centuries later, around 400 CE, the autocrat Samudragupta, the true founder of the Gupta Empire, claimed descent from the Licchavi aristocrats who once defied Ajatashatru. But neither Samudragupta nor his predecessors and successors had republican pretensions. The allure of all that power, concentrated in a single office, was simply too much. Republics did not return to the Gangetic Plains for 2,000 years. Today, just as it did many centuries ago, collective rule faces the same problems as before: dissension, division, and inequality as opposed to well-organised strongmen. History teaches us that republics must answer their internal contradictions if they are to survive; they also teach us that autocracies exploit these contradictions, are worse at answering them, and are better at avoiding accountability for them. And so the cycle continues.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)

Posing as teachers they should sow quarrels among their princes. Tactics of arts academia in India from Nehrus times. With nothing to prove their opinions they sow discord to retain power and influence. Divide and rule over the masses and appear moral and good doing it. Kanisetti misses the irony here. He should be the last to quote this. Or perhaps he bulk quotes without reading