One of the most common criticisms of the annual Soft Power 30 study is the conspicuous absence of India in the rankings. Admittedly, India’s non-appearance in the top 30 countries does give one pause. So much so, it is worth exploring why this is the case, looking ahead to see when India might expect to break into the top 30, and understanding what changes the government might need to usher in to do so.

For those unfamiliar with The Soft Power 30, it is an annual study produced by Portland, a strategic communications consultancy, and the University of Southern California’s Centre on Public Diplomacy. The annual report is built around a composite index that assesses the soft power resources of the world’s leading countries through a combination of objective metrics and international polling data.

The index – developed around Joseph Nye’s argument that the sources of soft power are based primarily on political values, culture, and foreign policy – is designed to give a comparative snap-shot of countries based on their soft power assets. It is not a measure of absolute influence, but more the potential for influence. Objective metrics are structured into six sub- indices: Culture, Digital, Education, Enterprise, Government, and Global Engagement. International polling data is drawn from nationally representative surveys of 11,000 people in 25 countries, covering every region of the world. Survey respondents rate countries based on a set of factors that are most likely to drive perceptions of a foreign country. These factors include foreign policy, culture, liveability, and technology exports, among others.

Also read: India is yet to recognise the soft power of making its rupee an international currency

While the study only publishes a list of top 30 countries, there are a total of 60 countries included in the study, of which India is of course one. The Soft Power 30 has been produced annually since 2015, but it draws on the earlier work of the Institute for Government Soft Power Index which was published in collaboration with Monocle Magazine from 2010 to 2014.

The 2016 edition of The Soft Power 30 report identified India as ‘a country to watch’, arguing that an upward lift in its ranking (from 2015 to 2016) was likely the start of a trend that would see it break into the top 30 in the near future. Surprisingly, this prediction has failed to materialise. Not only has India not built on its earlier momentum, its overall ranking has actually fallen since 2016. So, what happened and how can India reverse the trend?

There are several factors at play driving what feels like an underperformance in the Soft Power 30 index for India. The first is that we need to recognise there is at least some element of Western bias to the concept of soft power, as developed by Joseph Nye. As conceived, and as borne out in some (but not all) of the Soft Power 30 metrics, developed-economy countries do enjoy an advantage. This, in turn, puts India at a relative disadvantage.

Also read: India cannot afford to be a soft power for next few years, says Ajit Doval

The other aspect of the index to bear in mind is that it is a composite measure, aggregating data across a diverse range of soft power metrics to produce a single score for each country. Thus, an especially poor performance in several of The Soft Power 30 sub-indices drags down a country’s total score. But this does not mean that such a country will not have clear strengths and useful tools in its array of soft power assets.

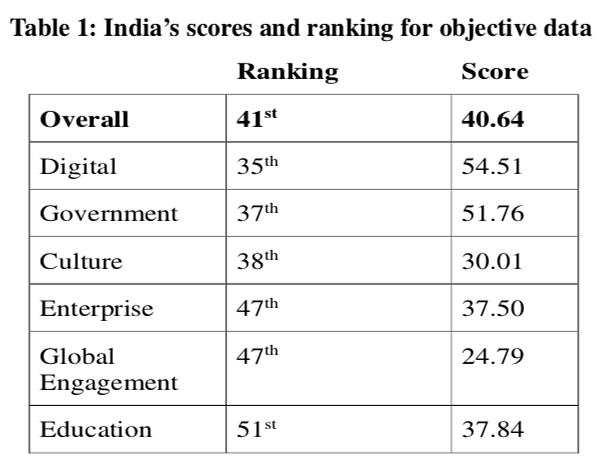

Bearing those caveats in mind, a breakdown of India’s performance across The Soft Power 30 can provide insights into both the factors dragging down India’s overall ranking, as well as the country’s soft power strengths that can serve India’s foreign policy priorities if used effectively. India’s biggest challenge, in terms of soft power assets – as assessed by The Soft Power 30 index – stem from the ‘harder’ elements of soft power. Said differently, it is systemic issues like corruption, poverty, inequality, gender inequality, and pollution that weigh on global perceptions of India, and thus its soft power. Often the most commonly covered topics on India in international media focus on these more negative stories. Subsequently, these issues have an outsized impact on international views of India, and not in a positive way. Table 1 below provides India’s relative ranking and scores for each of the objective data sub-indices.

Looking at India’s performance across the objective sub-indices, India’s strongest soft power assets are found in Digital, Culture, and Government. In the digital sub-index, Prime Minister Narendra Modi powers India’s extraordinary digital diplomacy reach, which is among the best in the world. Prime Minister Modi is second to only to US President Donald Trump for Facebook followers in other countries. This means India’s Government can reach a huge international audience directly through social media platforms. In the Culture sub-index, India benefits from 36 UNESCO world heritage sites, ranking 6th in the world; it is 13th for average tourist spend; 22nd for international tourist arrivals; and 23rd for entries into major international film festivals. India’s performance in the Government sub-index paints a mixed picture. India does well on some metrics that capture the vibrancy of being the world’s largest democracy. But it performs less well on measures that capture citizen outcomes and government effectiveness, such as the UN’s Human Development Index.

Also read: Attempts at remaking India are eroding its soft power globally

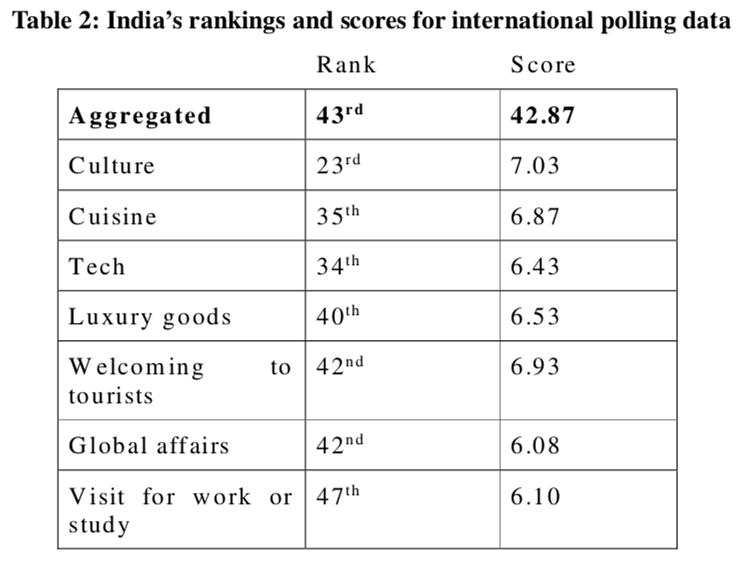

Turning to the international polling data we see a set of results that broadly reflect the objective data. India’s best performance in the polling, as shown in Table 2 below, is in Culture, where it ranks inside the top 30 at 23. It is encouraging to see India’s cultural assets cutting through to international audiences. Chief among India’s culturally-driven soft power assets are the richness of a millennia-spanning continuous civilization, the films of Bollywood, the global appeal of yoga, ubiquitous Indian cuisine, India’s huge (and often successful) global diaspora, and India’s cricketing prowess. Likewise, international public opinion gives India credit for its well-established digital and tech sector, with India’s ‘technology exports’ being ranked 34th out of a total of 60 countries.

With a better understanding of India’s performance across the different components of The Soft Power 30 index, we can turn our focus to what might be done to improve India’s relative soft power assets and the capacity to better leverage them. On the systemic issues that weigh on India’s soft power identified above, the Government should be – and likely already is – aware that these domestic issues have implications for India’s influence abroad. They are complex challenges that will take time to address.

In the absence of immediate solutions, it would be wise to focus on what the Indian government can control in the more short term. One action that would immediately benefit India’s soft power is an expansion of its diplomatic network, as well as the number of international cultural missions of the Indian Council for Cultural Relations. India would benefit significantly from more international platforms to engage global audiences and communicate not only what India has to offer the world in terms of its wider cultural offer, but also articulate its values, aspirations, and a clear vision for India’s positive role in the world.

Extrapolating from the international polling data on perceptions of India’s foreign policy – where it ranks 42nd out of 60 countries – there seems to be a lack of understanding around what India wants from the world, and what it stands to contribute. Again, a larger diplomatic network with expanded platforms for articulating India’s aspirations and vision would be a boon for Indian soft power. With greater understanding and more familiarity, international publics are likely to increase their trust in India and see it as a potential partner. In combining India’s excellent digital reach with a greater international diplomatic presence, India will be better able to explain itself and its aims to the world, as well as leverage new platforms to engage international audiences with its formidable cultural assets. Results would not come overnight, but if resources could be mobilised, the returns on investment for India’s influence abroad would be significant.

Jonathan McClory is the creator and author of The Soft Power 30 and General Manager for Asia at Portland.

This article was first published in India Foundation Journal, March-April 2019 issue. It is being reproduced here with permission.

We should have done better.

Let’s work hard, Not for ranking but for our own selves.

I went limp after reading this story.

It would be interesting to know our ranking prior to 2016 to make a fair analysis of how we’ve fared and the areas we need to work on.

At the moment, Bollywood, chicken tikka, Yoga.