King Janaka, better known to Indians as the father of Sita, once invited learned Brahmins to celebrate a lavish ritual. Videha, the kingdom over which he ruled, was in the east and viewed as a backwater by the intellectual elite of the western regions of Kuru-Panchala, the bastion of Brahminical culture. Perhaps wanting to impress upon his guests the intellectual vibrancy of his own region, Janaka challenged the assembled Brahmins to a contest that would determine the most learned person among them, offering the winner a thousand cows with their horns and hooves adorned with gold.

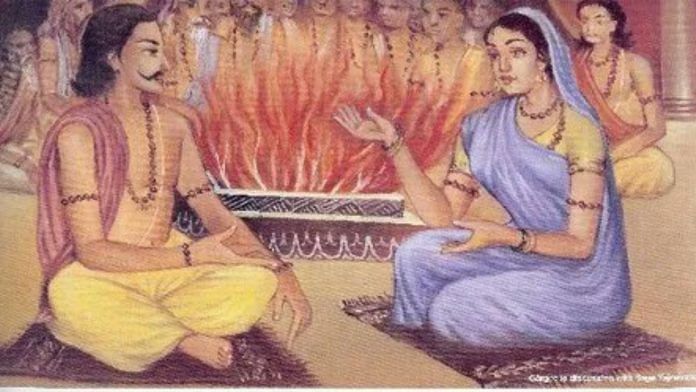

Yajnavalkya was a prominent philosopher of Videha, and he forthwith laid claim to the prize, ordering his pupil Somashravas to drive away the cattle. Naturally, the other Brahmins were incensed and challenged him to a debate. There were eight of them, seven men and a woman. Her name was Gargi Vachaknavi.

Women of strong character and formidable intellect are often the object of both disdain and angst in dominant patriarchal systems. Over two millennia ago, Gargi proved to have a sharper intellect and a stronger character than all her male colleagues assembled in Janaka’s court. And she knew it. Gargi was the only philosopher to question Yajnavalkya twice, and, after her second question, she effectively told the men to shut up.

Gargi began by posing a series of questions to Yajnavalkya, aimed at exposing his ignorance and his arrogance in daring to claim the prize. Tellingly, her questions used the metaphor of weaving, which was traditionally associated with women. She asked: “Yajnavalkya, tell me—since this whole world is woven back and forth on water, on what, then, is water woven back and forth?” The words “back and forth” refer to the movement of the shuttle during the weaving process. “On air,” replied Yajnavalkya. The series of questions continued, when, finally, the weft on which the worlds were woven was revealed to be Brahman. At this point, Yajnavalkya told Gargi to be careful and not ask further questions about a reality that one should not probe into extensively. Gargi became silent.

She returned to the fray after all the men in the group had completed their questioning and failed to defeat Yajnavalkya. Her remarks at the outset directed at her male colleagues were noteworthy. “Distinguished Brahmins!” she said. “I am going to ask this man two questions. If he can give me the answers to them, none of you will be able to defeat him in a philosophical debate.” Gargi here arrogated to herself the burden of finally defeating Yajnavalkya, something she knew the men in the group were not equipped to do. She claimed to be smarter than all other Brahmins, except perhaps Yajnavalkya.

Her questioning would settle the latter issue. Her verbal challenge to Yajnavalkya was remarkable in its audacity and use of martial language. “I rise to challenge you, Yajnavalkya, with two questions, much as a fierce warrior of Kashi or Videha, stringing his unstrung bow and taking two deadly arrows in his hand, would rise up to challenge a rival. Give me the answers to them!”

Also read: Who brought Sanskrit to Baghdad? This is how Iranian Buddhists, Zoroastrians changed Arabs

The greatness of Gargi

Continuing with the weaving metaphor, Gargi asked Yajnavalkya what everything in the universe—below the earth, above the sky and everything in between—is woven back and forth on. She was asking, in other words, what the ultimate substratum of the universe, of reality, was.

Yajnavalkya’s final answer was that everything was woven upon the imperishable—akshara. “The imperishable,” he explained, “is neither coarse nor fine, neither short nor long. At its command, the sun and the moon stand apart, as do the earth and the sky. This is the imperishable, Gargi, which sees but can’t be seen; which hears but can’t be heard; which thinks but can’t be thought of; which perceives but can’t be perceived. Besides this imperishable, there is no one that sees, no one that hears, no one that thinks, and no one that perceives. On this very imperishable, Gargi, space is woven back and forth.”

Confronted by the profundity of this philosophy, Gargi was stunned into silence. She recognised the superior philosopher standing in front of her. He deserved to take the cows and the gold, she now recognised, because he was clearly superior to all the assembled Brahmins. Perhaps she also recognised in Yajnavalkya a worthy opponent and interlocutor, and in recognising this she also demonstrated her own superiority to the other male Brahmins, who failed to recognise it.

Having acknowledged the superiority of Yajnavalkya, Gargi turned to her weak but proud male colleagues with this salutary advice: “Distinguished Brahmins! You should consider yourself lucky if you escape from this man by merely paying him your respects. None of you will ever defeat him in a philosophical debate.”

What a remarkable episode this was. Remarkable in the first place because a woman was permitted to enter the conclave of male philosophers. Even more remarkable that she assumed a leadership role in such an assembly and had the audacity to tell the men to shut up.

As so often happens in the cultural history of India, an exciting and pathbreaking figure emerges like a meteor in a dark sky only to recede without leaving a trace. One tiny and tantalising hint of her progeny is found in the lineage list of the Bṛihadaranyaka Upanishad (Madhyandina Recension) where there are three references to the “son of Gargi” (gargiputra).

Such was the fate of Gargi, a philosopher of unquestioned ability, strong enough to stand up to her male counterparts but confident enough to recognise a superior philosopher. We must be thankful to the composers of the oldest Upanishad for preserving this gem of a story. But as it often happens to strong women in history, later cultural transmitters have wittingly or unwittingly erased this great woman philosopher from the collective memory.

Further readings:

Brian Black, The Character of the Self in Ancient India: Priests, Kings, and Women in the Early Upaniṣads. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2007.

Steven E. Lindquist, The Literary Life of Yājñavalkya. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2023.

Patrick Olivelle is Professor Emeritus of Asian Studies, The University of Texas at Austin. He is known for his work on early Indian religions, law, and statecraft. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)

I continually find it amusing when feminist apologists bring up this episode. He almost makes it sound like she was the victor when indeed she was defeated along with everyone else.

Feminist apologists will try to turn a molehill into a mountain.

This is an anachronistic view of Vedic culture — interpreting or understanding ancient Vedic civilization, particularly in the context of India, through the lens of contemporary values, beliefs, or societal norms. This view often involves projecting modern ideologies, practices, or understandings onto the Vedic period

(BTW “Janaka” was the title of all Kings of Videha, not just the father of Sita.)