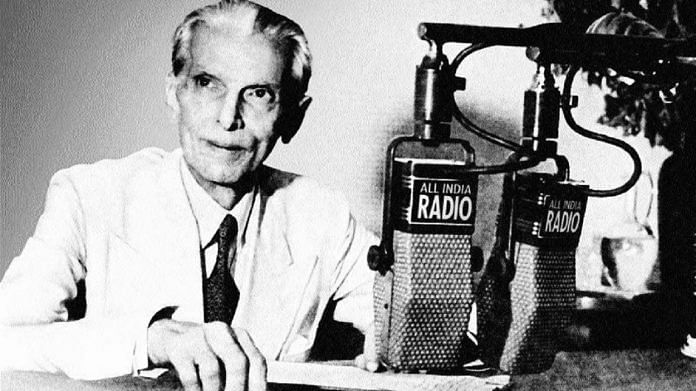

Ironically, in both India and Pakistan, Jinnah’s name and legacy was dragged into controversies at premier educational institutions.

The opening days of May 2018 have been very unsympathetic to the legacy of Muhammad Ali Jinnah— not just in Aligarh but also Islamabad. Ironically, in both places, his name and legacy have been associated with controversies at premier educational institutions.

In Aligarh, his association with Muslim nationalism is causing trouble, and right-wing forces continue to besiege the AMU Students’ Union office for a portrait of Jinnah. In Islamabad, however, the parliament has besmirched his memory by passing a unanimous resolution to rename the center of physics at the Quaid-i-Azam University – from that of the Ahmadi Muslim Nobel laureate Abdul Salam to the Muslim scientist Abu al Fath Abdul Rahman Al-Khazini.

The Ahmadis are not recognised as Muslims since an ordinance was passed in 1984. The resolution to drop the Ahmadi professor’s name for the Ppysics centre was moved by politicians who wanted to win some right-wing votes.

Hearing about the move, I am reminded of what Ghalib once mused:

I have none of the hallmarks of a Muslim; why is it that every humiliation that the Muslims suffer pains and grieves me so much? (Ghalib,1994, as quoted by Jalal, 2002:1).

By dropping Salam’s name, Pakistan’s parliament went against Jinnah’s foundational promise to its constituent assembly that Pakistanis are free to go to any place of worship, that Pakistanis may ‘belong to any religion, caste or creed—that has nothing to do with the business of the state‘.

After all, Quaid-e-Azam, the father of the nation, had said that, with time ‘Hindus would cease to be Hindus and Muslims would cease to be Muslims, not in the religious sense, because that is the personal faith of each individual, but in the political sense as citizens of the state.’

The part of him that was the architect of the two-nation theory could co-exist with the side of him that felt citizens could now focus on the important task of nation-building, forgoing personal identities.

But neither Pakistanis nor Indians have understood how Jinnah traversed these two strains, and have not allowed this dual legacy to sustain.

And then came the perverse and disturbing comedy of errors from Aligarh. Hooligans beat up Muslim students for not being Indian enough because of a Jinnah portrait. Utterly lacking a sense of irony, the members of the Hindu Yuva Vahini were saying: How dare the university hang the portrait of Jinnah, a man who called upon Muslims to move to a separate state to avoid being cornered by India’s Hindu community?

Here, I want to ask the Hindu Yuva Vahini a question (from the movie Khosla Ka Ghosla): “Aap party hain ya broker?” You are bent upon proving Jinnah right.

These two events now make me look at the hapless Jinnah quite kindly, although I have had mixed feelings about him for long.

In Islamabad, and at Quaid-i-Azam University, there is massive confusion regarding what and who they just renamed.

To Islamabad, all I can do re-gift a copy of the finest 1960s Urdu short story called Dhanak by Ghulam Abbas – a dystopian story of how the mullahs take over the country and tear apart the fabric of society and create anarchy. When it was published, Pakistanis had reacted with anger, saying it was an insult to their religion. Many at that time said it was far-fetched, and derided it with a ‘kuchh bhi, yaar’ eye-roll. ‘Why would Muslims kill other Muslims and bomb mosques?’ some asked. Two decades later, the story turned out to be prophetic, a frightening manual for those who wanted to create an ‘ideal society’.

To India, my message as a Pakistani is: ‘I am the Lorax. I speak for the Other’. (From the children’s book The Lorax by Dr Seuss)

Dear Indians, after you have done purifying (shuddhikaran) architecture, street names, literature and textbooks, sanitising research institutions and defanging universities, the media and the judiciary—will you also, like Pakistanis, turn on each other to find who best amongst you is the ‘purest Hindu’?

As Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan sang for us:

“Mere baad kisko sataaoge?

Mujhe kis tarah se mitaaoge?

Kahaan jaa kar teer chalaaoge?”

Aneela Babar is a gender and cultural studies specialist, and the author of ‘We Are All Revolutionaries Here: Militarism, Political Islam and Gender in Pakistan’.