The Bombay Plan, drafted 80 years ago by industrialists such as JRD Tata, GD Birla and Purushottamdas Thakurdas, was not meant to be revolutionary. But it took India and the world by storm— just for a year though, before subsequently disappearing from public view. Nonetheless, it played an integral role in shaping India’s economic trajectory in 1947, with many of the plan’s ideas being used in subsequent Five Year Plans. As the new government prepares the 2024-2025 Union Budget, perhaps it is time to look at The Bombay Plan’s long-term vision for Independent India.

It holds lessons for India today on how to overcome a host of challenges, especially along the lines of public health and education. The plan’s focus on living standards and access to basic public goods and services, while pursuing a high-growth agenda is worth revisiting as India approaches its 100th year of Independence.

In 1944, on the heels of the Bengal Famine and WWII, the Quit India movement, the doyens of Indian industry, who played a crucial role in business and politics, and respected economists and technocrats including future Railway and Finance Minister John Matthai, Ardeshir Dalal, and Ardeshir Shroff, came together to write The Bombay Plan, formally known as A Plan of Economic Development for India.

This now-forgotten document tried to set out a long-term approach to addressing concerns around unemployment, skillability, inflation, inequality, and living standards. It did so by pushing for a focus on the country’s agriculture and services sector, while investing heavily in heavy industry and parallelly improving living standards through targeted interventions in health, primary and secondary education, and food production and distribution.

It outlined a pathway for India’s development, by putting it on a high-growth trajectory with the central aim of bringing “about a doubling of the present per capita income within a period of fifteen years”. The writers called for India to adopt an import-substitution model and limit the role of foreign funding, supporting the view that India needed to be self-sufficient and develop its own domestic industries, a global trend at the time.

Leaving the intentions of the planners aside, which has been discussed in a separate article, it was revolutionary for its times because of its focus on the role of the state in the economy, and for its emphasis on significant investments in basic public goods such as healthcare, and affordable housing.

Despite massive strides in these fields, challenges persist today.

But this is a momentous time in some ways, given the global economic environment, with the growth of most major economies looking weak, Indian bonds being listed on global indices for the first time, a massive dividend from the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), and a coalition government returning after 10 years. This year’s Budget has the potential to act as a vision document of the new government’s long-term goals.

While physical and digital infrastructures have been major priorities in the past few years, with significant strides in the same, allocations to human capital, i.e. education, healthcare, and public health, to name a few, have remained unchanged, at less than 1 percent of GDP.

The Bombay Plan made it clear that investment in human capital is necessary for India to succeed. Such long-term investments equip citizens with the right skills to be able to contribute to the country’s growth. In essence, the Union Budget should consider taking this integrated approach to its spending priorities to ensure that India’s growth potential is truly unlocked.

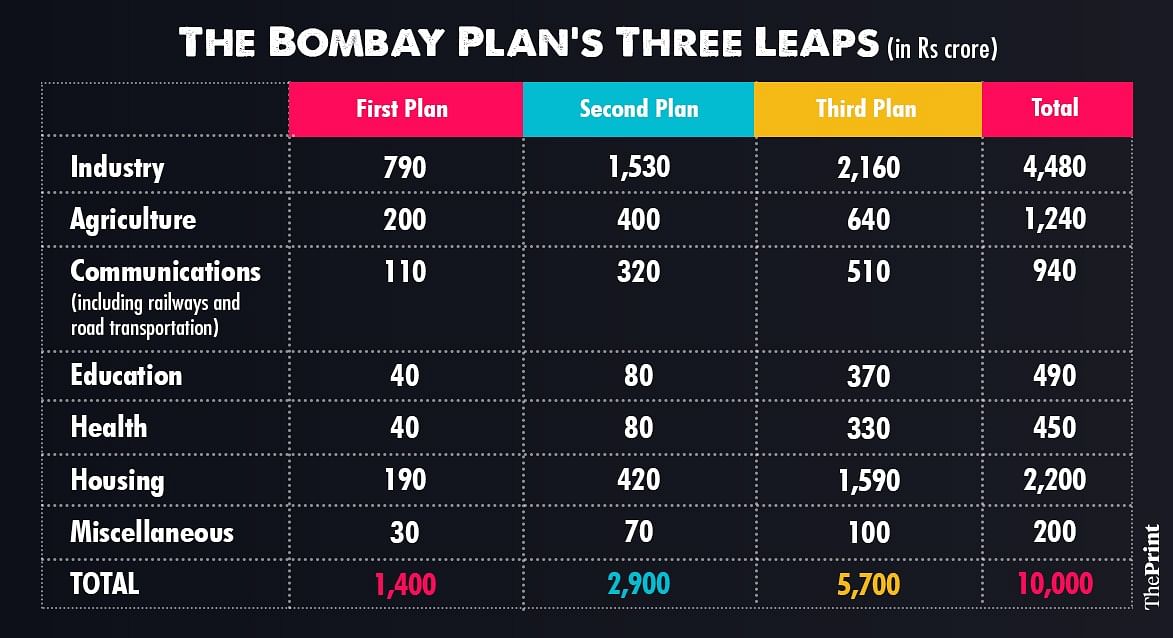

The Plan was centred on three ‘leaps,’ i.e. Five-Year plans, with refocused and prioritised sectors in each one, as seen below. The trajectory of India’s FYPs mirror these plans.

Also read: Budget 2024 must further India’s clean energy goals. Climate change is an economic problem

Not just business interests

The plan’s other main aim was to improve living standards for all Indians and define adequate living standards using a range of criteria from calorie intake, to the quantity of cloth required for clothes, basic health needs, education, and housing. It is unclear how the authors came to the conclusion that they did, but the Plan acted as a statement to show that prolonged economic growth, compounded with interventions in improving the quality of citizens’ well-being, can raise living standards.

The planners set out to explain what a minimum living standard for every Indian was. They emphasised the lack of food security for Indians, and that at current levels, the whole population of India will be hungry. They go on to spell out how much spending per person on average might be required to overcome basic hunger—approximately Rs 65 per person per year (1944 terms).

It also set out minimum housing standards for Indians, a feat that is yet to be achieved, despite attempts through Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) and Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY).

Based on a housing study done in Bombay in the 1930s, the planners concluded: “Adequate shelter against sun and rain and against the inclemencies of weather is yet another of the essential primary needs of human life. On the basis that a person should have about 3,000 cubic feet of fresh air per hour, the accommodation required would be about 100 square feet of house room per person.”

The planners provided evidence to indicate that this requirement of 100 square feet of housing per person is not met in most metropolitan areas. They observed that the rise of slums and high rents caused significant overcrowding in the country and argued that India needed to spend Rs 1,400 crore (in 1944), to meet minimum housing requirements—a tall order given the state of India’s economy.

The plan’s focus on other aspects of development, not just agriculture and industry, shows that it was not a statement entrenched in the business interests of the planners nor was it a ploy to maintain their position in the economy. It was an active attempt to engage in policy-making and provide recommendations to the British government and the INC to rebuild the economy after WWII.

Health and education also held great importance for the planners.

India’s life expectancy was exceptionally low in 1944, and while it has improved immensely since Independence, lifespans are highly unequal and shaped by access to essential services. The planners stressed two important areas: basic sanitation, which, barring vaccination rates, is still wanting; and curative measures, such as primary, secondary and tertiary healthcare.

The writers calculated that only 13 million people in the country had access to safe and reliable water supply, there was a doctor-to-patient ratio of 1:9000, and 74,000 hospital beds for a population of approximately 400 million, thus improving the overall quality of public health and access to healthcare would be a task. India’s public health situation is much better today. But it requires substantive interventions, from rising air pollution, heatwaves, floods, and poor sanitation, and must be a key focus area for the Indian state.

Similarly, primary and secondary education were viewed as key priorities for India’s development. The plan argues that “every person above the age of 10 should be able to read and write and take an intelligent interest in private and social life” as it fosters socio-economic stability and provides a pathway to employment.

They proposed the establishment of primary schools across the country, advocated for an increase in teacher salaries, and training courses for adults.

Regardless of the veracity of the plan’s statistics and its stated intentions, it highlighted that India’s economy and social fabric require immense support to uplift Indians out of poverty, bridge inequities, and truly improve living standards. The Bombay Plan was therefore not only a plan for India’s infrastructure and industry but also a guiding plan for human development, with the state playing a crucial role in its implementation.

As the new government prepares for the 18th Lok Sabha’s Budget session, the plan, 80 years on, holds lessons on how one might strike a balance between immediate economic priorities and long-term interventions to unlock India’s true potential.

Vibhav Mariwala is an independent researcher. He tweets @VibhavMariwala. Views are personal.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)

Socialist India is famous for devising such unsuccessful plans. Freedom fighters missed a trick by kicking out the British a bit early. They should have waited for India to become a developed country, holding them to ransom, and then kicked them out when their expertise was no longer needed. Now we are left struggling with the heavy lifting.