Pakistan’s mainstream media may have hid it well, but sectarian tension between Sunnis and Shias seems to be back, especially in the commercial capital of Karachi and some urban centres of Punjab. Although Pakistan’s state authorities and its supporters on social media have tried to project this conflict as an Indian conspiracy, the accusation does not explain the fact that a number of Deobandi parties, extremist, and militant groups have come together to harass the Shia population right in the eyesight of the country’s security apparatus. Violence has not begun, but its likelihood looms large. The fear generated through sloganeering is in itself harmful for the Shias.

The real question, however, is why has such tension returned? Why is it that all major Deobandi militant groups are back to knocking at the doors of Pakistan’s Shias? And why are non-militant Sunni religious groups, such as the Deobandis and Barelvis, trying to scare the life out of Shias, or anyone who is supporting Iran?

Many people I spoke with are linking the recent development with the Pakistani government and military’s desire to divert attention from retired Lt General Asim Bajwa’s scam of his large personal business empire in the United States. Some tend to see it in the context of pushing back the political opposition. Such explanations are worth thinking about but don’t sufficiently explain the reemergence of the Shia-Sunni discord or why the State would take such a major risk of unleashing danger that is tantamount to walking on a landmine.

Saving Asim Bajwa’s reputation may be necessary, but it doesn’t deserve such a risk. The missing piece of the puzzle is probably Iran, and perhaps Tehran’s links with China.

Also read: In Iran-China deal, Pakistan most interested in this clause — Delhi’s alienation from Tehran

Eruption of anger

It was in the second week of September that thousands of Deobandi followers took to Karachi’s main Shahrae Faisal road chanting anti-Shia slogans, referring to the community as ‘kafir’ (non-Muslim) and calling upon the state to ban Ashura, the Shias’ main religious event to mourn the death of Prophet Muhammad’s grandson Hussain in 680 AD. A prominent Sunni cleric even demanded an end to Muharram processions.

For Shias, the first month of the Islamic calendar, Muharram, is spent remembering the tragic incident that also lays out the fractious history and internal conflict of Islam dating back to the early years. This year, Deobandi clerics accused some of their Shia counterparts of committing blasphemy against certain controversial figures in Islamic history whom the Deobandis respect but the Shias don’t. This division is known and historic, but the sudden eruption of anger is strange.

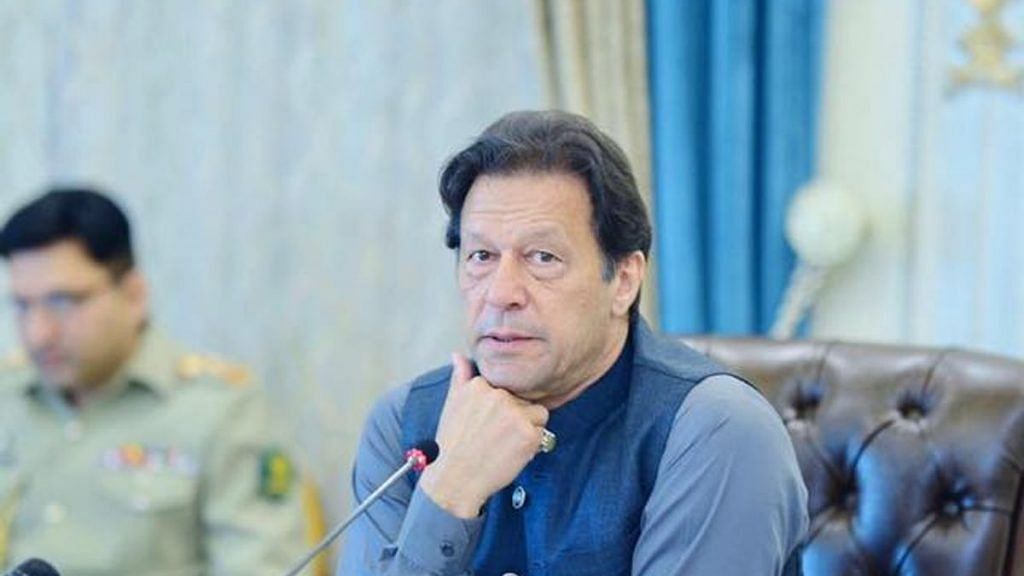

The Imran Khan government’s response, thus far, has been to stop the media from reporting on the matter. This is probably an attempt to contain any outbreak of violence, because Shias in Pakistan are a sizeable minority. They represent about 21 per cent of the total Muslim population, the highest number in a country after Iran.

However, violence is inevitable because the anger and anxiety on both sides seem to be mounting. There is also the fact that Deobandi ideology has been given a freer hand, as demonstrated by the passing of the Tahaffuz-e-Bunyad bill in July 2020 in the provincial Punjab Assembly. While incorporating blasphemy law in government rules even deeper, the bill is problematic due to its lack of consensus on key religious concepts between Sunnis and Shias.

One would imagine that the State would try to avoid any outbreak of violence or even tension. After all, Pakistan has reportedly witnessed the killing of approximately 4,847 Shias in incidents of sectarian violence between 2001 and 2018. Karachi saw the targeted killing of Shia doctors and lawyers in 1999, even before 9/11. The sectarian violence, which was irksome for the state, was finally brought under control as a result of the two key military operations against terrorism — Zarbe Azab (2014-17) and Radul Fasad (2017-19).

Interestingly, the Barelvis who are known for greater sympathy with the Shias also seem to have turned against them now. Although the ideological shift had started to become visible in the early part of 2010, the Barelvi Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP) joining the Deobandis against the Shias is even more dramatic.

The limited but highly dangerous Deobandi gatherings followed by the Barelvi TLP rallies expressing shared anti-Shia sentiment despite having divergent ideologies could blow up in Pakistan’s face.

Also read: Asim Bajwa’s dirty money is RAW saazish in Imran Khan’s Pakistan

Violence and influence

Like the Middle East, Pakistan could prove to be a whirlpool of sectarian tension and violence. Though the first instance of Sunni-Shia tension erupted around 1951 in Sindh, it built up more decisively during the 1980s. General Zia-ul-Haq’s regime looked away while the Anjuman-e-Sipah-e-Sahaba (ASS) took birth in Jhang, South Punjab in 1986. It later turned into the Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan (SSP) that became the mothership of all Deobandi militancy. It gave birth to Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ) during the early 1990s, and also the Harkat-ul-Mujahideen, Harkat-ul-Ansar, and later Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM).

During counter-terrorism operations by Pakistan, segments from the SSP, LeJ and JeM went into making the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). Some members of this even went on to join Daesh. The SSP was also one of the first organisations to fight in Afghanistan. Besides militancy, the organisation also engaged in politics. Its leader, Haq Nawaz Jhangvi, initially contested elections in 1988 from a Jamiat-e-Ulema-e-Islam–Fazlur Rehman (JUI-F) ticket, and later formed his own party. Around the time Haq was killed in 1990 outside Islamabad, Pakistan saw a lot of bloodshed, including sectarian violence, through the decade of the 1980s, 1990s, and the 2000s. Like the evolution of its militant wings, the SSP’s political face also evolved. One of its current forms is the group Ahle Sunnat-Wal-Jamaat (ASWJ), which is visible in electoral politics. The SSP and other militant groups are part of the Deobandi network that comprises militant outfits, political groups, and welfare institutions.

The network is so well spread out in the largest province of Punjab that there are over 20,000 staunch Deobandi voters in every constituency, which makes the group important for all political parties and builds their influence. The JUI-F, headed by Maulana Fazlur Rehman, is one of the most prominent faces of the network. It is instrumental in partnering with the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) and spreading the influence of Rehman’s network in Sindh and Baluchistan.

Also read: Iran becoming more secular, less religious, new study reveals

The Iran angle

The Jaish-e-Mohammed, which was considered as dedicated to Kashmir, began talking about sectarian issues as recently as early September 2020.

The need to hide Asim Bajwa’s financial sins is not sufficient reason to explain the sudden turn in JeM’s narrative. Though not going all guns blazing after Shias, its recent writings have clearly stated that it subscribes to the overall ASWJ ideology. The JeM, however, has taken a more aggressive position against the Ahmediyas and blasphemy, particularly challenging France on the Charlie Hebdo issue. These were matters that the JeM has avoided in the past. Its members that I spoke with would categorically say that they didn’t want to divert attention from jihad outside Pakistan.

To many, the internal shift in the Deobandi militant discourse indicates a growing Saudi influence. Indeed, in one of its publications on 12 August, the JeM seemed angry when it described the Foreign Minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi as “these traitor Makhdooms and their patrons will find their name in hell along with Pervez Musharraf [for abandoning the fight for Kashmir]”. Clearly, the reference to Kashmir was a peg to lash out at Qureshi for his recent rant against Riyadh. Most of the Deobandi militant organisations and its madrassa network are beholden to Middle Eastern patronage that started during the 1980s.

However, this in itself is not an indication that the JeM or the Deobandi network has grown independent of the Pakistani state. In fact, starting from early 2018, JeM literature had begun criticising Iran, something that was never done in the past. This was happening before the Pakistan government claimed that Masood Azhar and his family had gone missing.

The rise in sectarian rhetoric or focus on Iran, which is linked with the sectarian issue, even of militant outfits that were never known to dabble in such matters, indicates a critical shift. It is possible that the Deobandi network is responding to changes in larger Middle Eastern politics. Some argue that fear is being used as a tool to silence Shias from raising their voice in support of Iran, or against the peace deal between the UAE and Israel that may even extend to Saudi Arabia. The re-emergence of the TTP in bordering areas, the re-birth of the Malik Ishaq group of LeJ that is now more vociferously using a sectarian agenda, along with the presence of Daesh in areas of Afghanistan close to Pakistan, could pose a challenge for Iran.

It certainly raises questions about the security of Iran’s development projects in cooperation with China.

The silence of the Pakistani government can be explained as its urge to discourage domestic violence. However, it may also be to hide some internal divisions regarding its geo-political agenda — issues like recognition of Israel, a necessary containment of Iran, and its continued dependence on the US. It also raises questions about Pakistan’s attitude towards the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) and China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which as expert Andrew Small recently argued is coming down on Pakistan’s agenda. The silence on an ever-bloating sectarianism may turn out to be more strategic than tactical.

Ayesha Siddiqa is research associate, SOAS London and author of Military Inc; Inside Pakistan’s Military Economy. She tweets: @iamthedrifter. Views are personal.