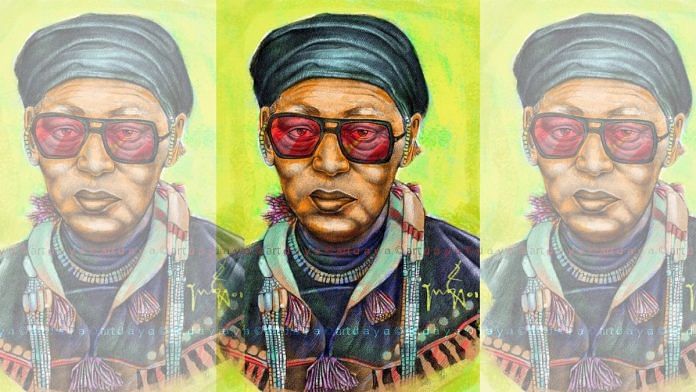

Lightning flashed for five nights and days over the village of Lungkao as the girl was being born, one chronicler recorded: The goddess Cherachamdinliu of the Bhuban cave had entered the womb of Karotlenliu to take human form. The teenage girl would, indeed, go on to make an empire tremble. Thrown into prison, legends hold, her guards sought to torment the girl by tossing snakes and scorpions into her cell, but she would casually play with the poisonous reptiles.

Eight years ago, as India’s new government intended to end the Nagaland insurgency forever, it announced the construction of a statue and memorial to Gaidinliu—the uncrowned queen of a rebellion against British power. Prime Minister Narendra Modi said Gaidinliu had been “deliberately forgotten.”

Furious protests broke out in Kohima against the plan, journalist Makepeace Sithou reported, with powerful Naga groups accusing the government of attempting to impose Hindu-nationalist history on the state. A memorial to Gaidinliu was eventually built—but hundreds of kilometres away in Imphal, dominated by ethnic-Meitei Hindus.

As savage ethnic cleansing proceeds apace in Manipur, the story of the queen’s memorial offers a useful prism to think about what comes next. Ever since the mid-1970s, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Singh has worked to build a national consciousness across the Northeast, locating nativist anti-colonial rebellions as the authentic foundation of the freedom movement.

To powerful political groups in Nagaland, though, this story seems an attack on their national political and religious experiences. The conflict in Manipur, they argue, is not just one powered by Kuki and Meitei ethnicity; Meitei churches have also been burned to the ground. The faith of the plains, and of the hills, are also at war here. And that has profound implications for how difficult peacemaking will now become.

Where does the uncrowned queen’s kingdom belong? Who ought to be her subjects, at least in memory?

An unwelcome freedom

15 August 1947 had not been a day of celebration in Kohima, the majestic work of historian John Thomas reminds us. Posters had been put up on the walls demanding Indians leave the region. The parade ground, where deputy commissioner Charles Pawsey hoisted the Indian flag, was deserted. Four years later, the Naga National Council (NNC) conducted its own plebiscite, shipping in forms rolled inside bamboo tubes that were taken from village to village.

Even though MK Gandhi had appeared willing to make concessions to Naga claims for independence, then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru was having none of it: “India cannot be split into a hundred bits. If you fight, we shall resist.”

The Assam Armed Police arrived into the Naga areas, armed with warrants for the arrest of top political leaders like T Sakrie. The villages of Jakhama, Kigwema and Phesama were burnt down. Khonoma suffered a similar fate. The great bureaucrat YD Gundevia had no evident qualms: “There was only one way in which incidents of this kind had been dealt with in the past: surround the village with a strong enough force, attack, kill if necessary and burn the village down. Relativist that I am, I have no quarrel with British norms.”

As the inevitable insurgency gathered momentum early in the next decades, the horrors of war etched themselves on the region’s memory. In July 1954, several people, including children, were killed at Chingmei; 60 women and children relocated to Yengpang were massacred. In Nagaland File: A Question of Human Rights, authors Nandita Haksar and Luithui Luingam have documented the carnage that followed, with dead bodies of insurgents being left out to rot, as well as endemic torture, rape and summary execution.

The brilliant intelligence officer SM Dutt understood coercion would not bring about the end of the insurgency. He tried to reach out to NNC dissidents, but with little success. The question was: what political narrative did India have on hand to lay claim to its eastern doors?

Also read: How women’s movement in Manipur became a platform for chauvinist elements

God and the state

Ever since the late 19th century, small groups of American Baptist missionaries had headed out into the Naga hills, seeking to draw the tribes into their faith. To India, it seemed clear that the missionaries were the locus of Naga resistance to the Indian State. Led by retired judge M Bhawani Shankar Niyogi, the official committee warned of dark plots to destabilise India, saying that “the manner in which the missionary movement goes on in certain places is clearly intended to serve some political purpose in the Cold War.”

The end of missionary activity had the support of Nehru, who wanted indigenous religious practices to be protected. According to anthropologist Richard Eaton, from 1947, only eight foreign missionary families remained in the region, and their activities were closely curtailed.

For reasons we don’t fully understand, author Arkotang Longkumer notes in his magisterial book on Hindutva in the Northeast, the decline in direct missionary involvement saw a dramatic increase in the adoption of Christianity. Large-scale revivals—where adherents underwent second baptisms, accompanied by mystic experiences—were seen among the Aos, the Lothas, the Angamis and the Chakesangs.

Frenzied religious prophecies—much of which foretold the imminent coming of Naga independence—might have been a reaction to the savageries of Indian counter-insurgency. Twelve adult men suspected of helping insurgents were tortured and beheaded in September 1960, one of many brutal abuses documented by Haksar and Luithui. In new segregated villages set up by the Army to sever connections between the community and the insurgents, starvation was setting in.

Angazmi Zapu Phizo, leader of the Naga nationalist insurgency, offered 50,000 troops to fight the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in 1962—a gesture that was ignored. For its part, the Intelligence Bureau, led by regional deputy director Dutt, set about negotiating with local leaders. The initiative focused on the common threat to the church and the Indian State from the Left-leaning insurgents.

Led by Thuingaleng Muivah, the General Secretary of NNC, and Brigadier Thinoselie Medom Keyho, a small batch of insurgents sought to break the impasse by travelling to China for training. The mission would lead to a fitful flow of arms from the PLA, authors Gurpreet Singh and Rajinder Singh Sandhu write in their paper, Naga Separatism in India and Role of External Powers. But the deep Christian feelings of the Naga insurgents made ideological cooperation difficult.

Llongri Ao and L. Kijungluba Ao were among the leaders who took charge of assailing communism from the church. There were dire warnings that new, China-trained atheists would burn down churches and punish atheists.

The new-found alliance between the Indian State and the church exploded into full public view. In 1972, the influential United States televangelist Billy Graham performed before thousands of people in Kohima, his spectacular production involving speeches simultaneously translated into 14 Naga languages. A million people are said to have attended the event.

Also read: India went to Myanmar to hunt down Manipur soldier killers. Now, it’s letting them slip away

Losers and winners in peacemaking

Even if it elided over many core issues, the nascent alliance between the church, and powerful elements of civil society, had created the contours for a settlement: In 1960, an agreement had been reached on the creation of the state of Nagaland, and efforts began to find a mechanism through which Tangkhul Nagas living in Manipur could also find representation in this body. India also began contacting Myanmar to find ways to reintegrate insurgent groups operating from its territory.

For Hindu nationalists, though, this was, at best, an incomplete solution. Rani Gaidinliu seemed to hold the keys,

The rebellion of 1931 led by Gaidinliu and her cousin Jadonang Malangmei had crystallised Naga grievances around taxes, forced labour, conscription into the Army and the behaviour of upper-caste Hindu officials. Eventually released from prison by Nehru, she moved back home. The new state of Manipur, though, proved remarkably reluctant to make concessions to her region of Zeliangrong. Gaidinliu went underground, a period during which her new religion—Heraka—consolidated and took form.

For the followers of Gaidinliu and the RSS, the way forward lay in a deeper immersion in a Hindu civilisational ethos. To other Nagas, the survival of their traditions and identity necessitated being walled off from the norms and cultures of the great populations of the plains.

Ever since 2018, the tempo of confrontation between these two visions has been sharpening. In 2018, Manipur chief minister N Biren Singh famously linked the Northeast to the story of the Mahabharata, claiming kinship to Krishna by claiming Rukmani as a Northeast princess. In Arunachal Pradesh, there have been efforts to entwine the local god Rangfraa with the larger iconography of Shiva.

The battle between assimilation and autonomy runs through all plural societies—but where primordial human impulses are entwined with politics and power, the carnage in Manipur teaches us, the outcome can only be carnage.

The author is National Security Editor, ThePrint. He tweets @praveenswami. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)