The body of the school’s office assistant had been doused in kerosene and set alight, still sitting on her chair, blood from her bullet-wounds pooling by her side. “There are so many children beneath the benches,” one gunman shouted, “go and get them.” Teenager Shahrukh Khan, shot in both knees, stuffed his school tie into his mouth so he would not scream. “The man with big boots kept on looking for students and pumping bullets into their bodies,” the schoolboy told journalists.

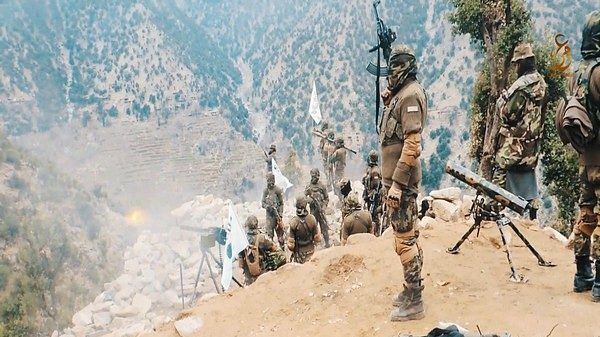

Eight years ago on Friday, Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan jihadists attacked the Army Public School in Peshawar, killing 149 people—132 of them children. The government rolled out a national plan to fight terrorism, centred around setting-up special military courts to prosecute jihadists. Aided by United States drones, Pakistan succeeded in eliminating top jihad commanders and reasserting its authority in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa.

Following the collapse of a ceasefire negotiated by former Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) chief Lieutenant-General Faiz Hameed, though, TTP terrorists have beheaded, ambushed police personnel, and staged public executions. Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa residents have been demanding the government act—but Islamabad has chosen to instead turn its fire on an older enemy.

Last week, Interior Minister Rana Sanaullah blamed India for attempting to assassinate Lashkar-e-Taiba founder Hafiz Saeed. The dossier claims the Research and Analysis Wing is operating a “vast network of terrorists“ through long-incarcerated gangster Omprakash Shrivastava.

Early this month, travelling along the Line of Control, Pakistan’s new army chief General Syed Asim Munir vowed to “not only defend every inch of our motherland but to take the fight back to the enemy.” Foreign minister Bilawal Bhutto has chipped in with invective against India’s prime minister Narendra Modi, calling him “the butcher of Gujarat”.

Islamabad has been strangely silent, though, on the growing threat to Pakistan from the TTP.

Also read: US engages with anti-Taliban group as global frustration rises against regime in Afghanistan

God’s own army

For the most part, military mottos inhabit the semantic space between rousing cliché and platitude. The French 1st Parachute Hussars—not always triumphant through their three centuries of service in wars across the world—philosophically remind soldiers of the Latin aphorism omnia si perdas, famam servare memento, ‘even if you have lost everything, there is still honour.’ The Swiss special forces more poetically—though just as alarmingly—inform volunteers that the path into the stars is rough.

The Pakistan Army slogan, though, is unusual in invoking an expressly theocratic conception: Iman, faith in Allah, taqwa, fear of Allah, and jihad-fi-sabillah. This term is explained on the website of Pakistan’s military public-relations service thus: “The real objective of Islam is to shift the lordship of man to the lordship of Allah on the earth.” The Pakistan Army is committed to “stake one’s life and everything else to achieve this sacred purpose”: There is a higher cause than the constitution.

For centuries, law scholar Onder Bakircioglu explains, classical Islamic theologians struggled with the question of when war was just. The consensus, he suggests, was that “the purpose of each war must be the promotion of Islamic values.” Following the Second World War, though, Muslim-majority states signed on to the United Nations charter, which prescribed that “armed force shall not be used, save in the common interest.”

The regime of the military ruler General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, however, rebuilt the Pakistani military—enshrining the notion of jihad at its core. General Zia was influenced by Islamist ideologue Abul A’la Maududi, who argued that Islam was more than a “hotchpotch of beliefs, prayers and rituals”. Islam was, in fact, “a revolutionary ideology which seeks to alter the social order of the entire world and rebuild it in conformity with its own tenets and ideals”.

For Zia—concerned with re-establishing the political authority of the Pakistan Army after its defeat in 1971—the attractions of this ideology were obvious. The leaders of the faith had an obligation to “seize political authority so that it may establish the Divine system on earth”. “An evil system takes root and flourishes under the patronage of an evil government,” Maududi asserted, “and a pious cultural order can never be established until the authority of Government is wrested from the wicked.”

The self-imagination of the military is evident in the army’s annual collection of essays by serving officers, called The Green Books. In the 1994 Green Book, Brigadier Saifi Naqvi noted that “Pakistan is an ideological state”. The army, he argued, was thus “responsible for the defence of the country, to safeguard [its] integrity [and] territorial boundaries, and the ideological frontiers to which the country owes its existence”.

Later editions of The Green Books, scholar C. Christine Fair has noted, were replete with essays critical of Pakistan’s involvement in the war which began after 9/11. The essays speak of the wellsprings of ideological sympathy within the military for the jihadist project.

Also read: Taliban stands divided. Why it has implications for the world and India

Talking to terrorists

Following 9/11, expert Daud Khattak has written, the Pakistan Army repeatedly sought accommodation with terrorists—allowing jihadists to control territory along its borders. The army signed an agreement with jihadist Nek Muhammad Wazir in 2004, who promised his forces would unleash themselves on India like “Pakistan’s atomic bomb”. The government even signed a peace deal with Fazlullah—the commander of the jihadists responsible for the school attack—just six months before the carnage.

Even though the peace deals—without exception—disintegrated, support for a rapprochement remained strong across the establishment. This had something to do with pragmatism: The option was a murderous civil war. The Islamic state of the jihadist imagination was, however, one close to the army’s own conception of Pakistan.

Two generations of post-Zia officers—who emerged from a pietist middle class that defined itself in opposition to the westernised elite—had been taught to see themselves as a vanguard of new, faith-centred Pakistan. This cohort includes General Munir, the son of a conservative religious family, who memorised the Quran while serving as a Lieutenant-Colonel.

Lieutenant-General Ahmad Shuja Pasha, ISI chief from 2008 to 2012, thus described TTP jihadist Fazal Hayat as a “true patriot”. General Ashfaq Kayani, who succeeded Gen Pervez Musharraf as army chief, also backed negotiations. Former prime minister Nawaz Sharif, elected in 2013, threw his weight behind dialogue with jihadists. So did former prime minister Imran Khan, who came to power in 2018.

Following the Army Public School massacre, public engagement with the TTP became difficult—but didn’t stop. To the outrage of families of the victims of the massacre, TTP spokesperson Liaquat Ali—also known as Ehsanullah Ehsan—was quietly allowed to escape from prison. Faiz secured the release of top TTP jihadists and began negotiations.

Late summer, as violence inside Pakistan surged, former army chief General Qamar Javed Bajwa told lawmakers of the options. The army could launch an offensive against the TTP, he said, but the country would have to be “prepared for the reaction”. Then, two weeks ago, the TTP made the choice for the military, ending its ceasefire.

Islamabad has, predictably, responded by ignoring the threat, and turning on a more politically useful enemy.

Also read: Pakistan’s new ISPR chief is son of Osama-linked scientist who said djinns can make electricity

The wrong enemy

Even as the ISI engaged with the TTP, it began accusing India of ties to the jihadist group. In a dossier released in 2020, Pakistan claimed the school attacks had been masterminded by an Indian-supported terrorist it called Malik Faridoon. There was no mention of Faridoon, though, in the official investigation of the case by Peshawar High Court judge Mohammad Ibrahim Khan. Earlier, in 2016, Pakistan’s military identified the mastermind of the attacks as Umar Mansour, who was killed in a drone strike in Afghanistan.

The dossier also misidentified officials and place names. There was no chief of the Research and Analysis Wing named Ajit Chetorvedi; the reference, likely, to Ashok Chaturvedi, who served from 2007-2009. Former spy chief Vikram Sood’s surname was misspelt, as was that of ambassador Gautam Mukhopadhaya. Dehradun, according to the dossier, is in Haryana.

Last year, Pakistan issued another dossier claiming India was training Islamic State jihadists at three camps. Latitude-longitude coordinates for the camps, though, turned out to point to a muddy lake in Jodhpur, and a clump of trees between two parking lots in Gulmarg.

The poorly prepared dossiers did little to dispel international scepticism about Islamabad’s claims. Their real objective, though, was to seize the low ground—domestic politics. By invoking an external threat, the army and Imran Khan sought to rally the public behind the ruling establishment. The dossier was released soon after former prime minister Nawaz went for the army’s jugular by publicly indicting General Bajwa for manipulating Pakistani politics.

Last week’s dossier reads from the same toxic script. This time, Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif and his new army chief are playing the India card against Imran and his supporters within the military. Even if the tactic works, however, it comes with costs. And the hardening of anti-India feelings legitimises jihadist groups like the Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Muhammad. That, in turn, raises the prospect of crisis-inducing terrorism in Kashmir, which would undermine Islamabad’s efforts to heal its economy.

Even though the dossier might win the ruling establishment some applause from nationalists, it isn’t the map Pakistan desperately needs to extricate itself from the minefields it has laid for itself.

The author is National Security Editor, ThePrint. He tweets @praveenswami. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)