From his office on the banks of the Chenab, Inspector General BCA Lowther patiently watched the detritus of the storm wash up: Three hundred maunds of grain, a little over 11 tonnes, animals, quantities of gold, jewellery, utensils, and, strangely, one gramophone. In Kotli and Seri, Lowther reported, Hindus were “almost completely destroyed.” Twenty men, or so, had been killed in the rioting of 1932, Dalits had been forced to embrace Islam, and some Sikhs had their hair shaved off. The brigand chief of the mountains, Khima Khan, had supervised the violence, with the help of village Lambardars, or headmen.

On Monday, Jammu and Kashmir Chief Minister Omar Abdullah defiantly scaled the walls of the martyrs’ graveyard at the shrine of Khwaja Bahauddin Naqshbandi, where 22 protestors who were shot dead by soldiers of Maharaja Hari Singh on 13 July 1931 are buried. Local police, alleged to be acting on the instructions of Lieutenant Governor Manoj Sinha, had locked ministers and legislators into their homes and barred a procession to the graveyard.

For decades, leaders of Kashmir’s pro-India parties have cast the 13 July massacre as the moment when the mass movement against the Dogra monarchy began, leading on to Independence. In 2020, though, Martyrs’ Day was dropped from the list of official holidays, together with former J&K prime minister Sheikh Muhammad Abdullah’s birth anniversary. The government then declared its intention to celebrate Maharaja Hari Singh’s birthday instead.

This project of historical erasure is reopening Kashmir’s deepest wounds. The truth is that the events of 1931-1932 were not, as ethnic Kashmiri politicians represent them, a secular revolt. Yet, the Dogra state was also a sectarian monarchy, determined to uphold the Hindu interest over its Muslim subjects.

For many Muslims, the message from this Martyrs’ Day is that it doesn’t matter who the community votes for: Kashmir’s identity and history will be decided by Hindu nationalist power, not their democratic choices. The debate Kashmir does desperately need — on identity, religion, and on the wounds that decades have done so little to heal — has been placed even further out of reach.

The battle at the jail

For much of the summer of 1931, tensions had been building up: First, a constable at the Jammu Central Jail was accused of desecrating the Quran, and then torn pages of the book were found in a Srinagar drain. Then, Abdul Qadeer, an ethnic-Punjabi cook serving a European visitor, was charged with delivering a seditious speech at the Shah-e-Hamdan shrine in Srinagar. Large crowds gathered to support Abdul Qadeer as he was driven to the trial court. An official inquiry into the events was recorded, and so authorities decided to conduct the trial inside the prison.

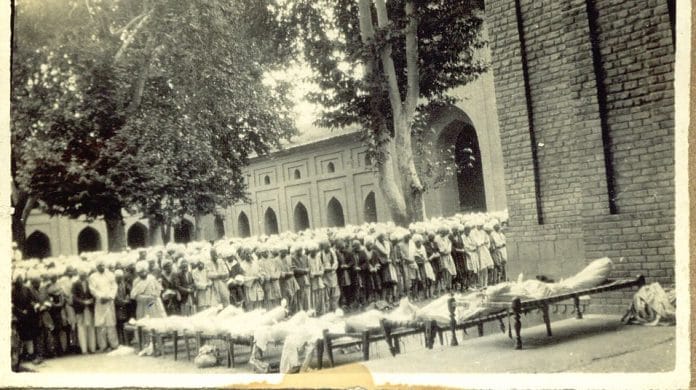

Then, on the morning of 13 July 1931, police opened fire on thousands of protestors massed at the prison gates. The crowd, as it bore the dead bodies through Maharajganj, looted Hindu-owned shops. Local Muslims alleged that Hindus later retaliated by attacking their properties, with the help of troops.

For a complete understanding of why tensions around religion exploded in 1931, historian Chitralekha Zutshi has argued, the broader context is key. From the late 1920s, the Great Depression had begun to choke Kashmir’s economy. Agricultural prices fell, leading rural workers to seek work in the cities. The urban factories, though, were in crisis. Through the countryside, Zutshi writes, moneylenders were foreclosing loans and taking over the lands of peasants.

Twenty-six years old in 1931, a graduate with a Master’s degree in science from Aligarh and employed in Kashmir’s education department, Sheikh Abdullah was part of an embryonic class of middle class Muslims seeking political representation and power. From the 1920s, Abdullah had been at the forefront of a group advocating for more job opportunities for Muslims. MK Gandhi’s arrest in the summer of 1930 had seen Kashmir shut down in solidarity, a sign of emerging mass politics.

From the court’s perspective, there was another issue. In March 1931, Mirwaiz Atiqullah of Srinagar, the hereditary spiritual leader of the city’s Muslims and a key supporter of the Maharaja, had passed away. A bitter succession struggle ensued, with Yusuf Shah battling Muhammad Ahmadullah Hamadani, the representative of a rival branch of the family.

Even though the job was not one that had a genuine popular base, the rising tide of religious tension would propel him to leadership of a movement that was just beginning to form.

Also read: India needs to focus on winning in Kashmir, not fighting Pakistan

Fighting for the faith

Like most of India’s princely states, Kashmir had high taxes and spent more on the upkeep of the monarchy than on education, healthcare, and public infrastructure. This hurt both Hindus and Muslims, but, as historian Mridu Rai has written, the Dogra state went to some lengths to assert its religious credentials. For example, cow-killing carried a ten-year prison sentence, while goat sacrifices were banned except on just a few, specified days. Those who chose to convert to Islam lost their rights to inherit ancestral lands.

Kashmir’s foreign minister, Albion Rajkumar Banerji, famously said that the state’s Muslims were treated like “dumb, driven cattle.”

Even though Muslims made up more than half of Kashmir’s population, historian Ian Copland records, Hindus and Sikhs held 78 per cent of gazetted appointments compared to the 22 per cent for Muslims. The Tehsildars of Kotli and Rajouri, the Naib Tehsildars of Bhimber, Naoshera, Kotli and Rajouri, and the Superintendent and Deputy-Superintendent of Police at Kotli were all Hindu or Sikh. In Mirpur, over nine out of ten Patwaris, or land record keepers, were Kashmiri Brahmins.

For a range of political forces in Punjab, this pool of resentment represented opportunity. The Khalifa, or chief, of the Ahmadiyya sect, Mirza Bashir-ud-din Mahmud Ahmad, ordered a concerted missionary push. Gurdaspur, the Ahmadiyya headquarters, was close to Jammu, and the sect claimed that Jesus Christ, revered by all Muslims as a prophet, had been buried in Srinagar. Funding from the Ahmadiyya enabled Sheikh Abdullah to resign his job, Copland writes, and commit himself full-time to politics.

The Majlis-e-Ahrar — which, among other things, would spearhead the movement to proscribe Ahmadiyya as non-Muslims in Pakistan — similarly thought it had found an issue on which it could distinguish itself from other parties. The Muslim League and Punjab’s powerful Unionists were allied with the Raj. The Majlis styled themselves as revolutionaries, opposing the presence of the British and the traditional rule of landlords and princes.

Also read: Definite change in Kashmir. Violence exists only because terrorists have adapted, Army hasn’t

A problematic legacy

Facing widespread resistance, the Dogra regime unleashed coercion. Late in September, Sheikh Abdullah was arrested. Five men protesting his arrest were shot dead in Srinagar, and another 22 Muslims were killed in Anantnag. The next day, Muslims in Shopian turned on the police, beating up guards posted outside the town’s mosque for Friday prayers. Pandit Hari Kishan Kaul and his brother Daya Kishan Kaul, the Maharaja’s key advisors, responded by imposing martial law. Local Muslims were forced to wear rosettes in royal colours, Copland writes, and over a hundred were publicly flogged.

Events moved rapidly toward a crisis. The Muslims of Mirpur and Jammu came out on the streets in response to the state’s violence, demanding Sheikh Abdullah’s release. Large crowds demanded that the Maharaja concede to their calls for religious liberties, restitution for riot victims, and proportional representation in the civil services. The shaken British resident in Srinagar, Courtney Latimer, forecast “widespread rebellion.”

The legacy of the 1931-1932 crisis is profoundly complex. There’s little doubt religion had played a key role in fostering political consciousness in Kashmir. For generations afterward, it would exercise an often-poisonous influence on public life. Few politicians in the region, either Hindu or Muslim, have made a serious effort to acknowledge, let alone exercise, the profound impact of communalism on Kashmir’s public life.

Yet, the events of 1931 were also the foundations on which Kashmir’s accession to India was built. The end of the crisis saw the establishment of a legislature in Kashmir, although with a franchise limited to those paying Rs 20 a year in land revenue. Muslims made genuine gains, especially in education and representation. For his part, Abdullah transitioned away from the chauvinism of the forces that shaped 1931, allying himself with the Indian National Congress and the broader freedom movement.

Seeking to erase 1931 killings from Kashmir’s political memory is to tell the Valley’s Muslims that they are condemned to suffer a lesser kind of citizenship. From there, the road heads inexorably back to an ugly, fractured past.

The author is Contributing Editor at ThePrint. His X handle is @praveenswami. Views are personal.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)

I enjoy Praveen Swami’s writings. However in this case – he has cherry picked bits of history to build up a pre-concieved narrative.

First – The 1931 loss of lives, was neither the first nor the the last of the violent suppression/s of public opinion in the region’s long history…excessive use of force is bad and condemnable. However – mourning it as a martyr’s day post-1948 and keeping this emotional hurt in perpetual memory is bad politics.

Second – Since this event highlights, actions by Dogra rule; implicitly it pits Jammu region vs Kashmir region; This is bad for National security of India.

Third – If the intention is to pay homage to freedom struggles in J&K – then there would be alot of other events – which should be taking precedence – Viz, Liberation of Rajouri, Link up of Poonch, Martyrdom of Mirpur, Kotli, Skardu, garrisons etc etc.

Political Islam is very bad for India. It brings out right wing reactions from other communities. And leads to a chain reaction. India needs peace and progress. This kind of political stunts by Abdullah family are only to keep themselves relevant.

Food for thought?