The evening began with almost as much agony as it would end: Emerging from his car into the skating rink where America’s future would be decided, Vice-President Richard Nixon slammed his knee into the door. Two weeks earlier, Nixon had spent 12 days in hospital, enduring a post-surgical infection inflicted by an identical accident. He headed into his historic debate with President John F Kennedy wan and exhausted, looking “better suited for going to a funeral, perhaps his own,” journalist David Halberstam wrote.

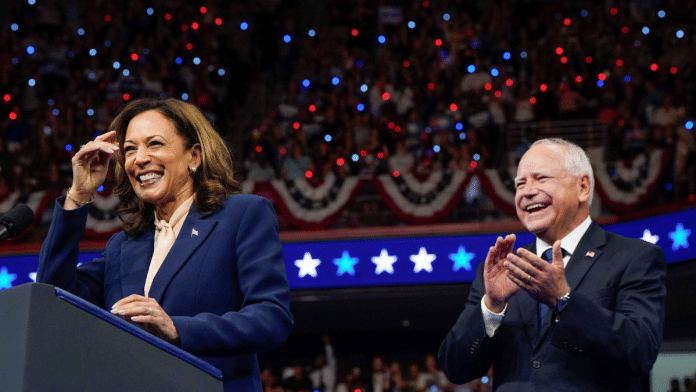

Late on Tuesday night, over 70 million Americans—not counting digital streaming—watched another Vice-President, Kamala Harris, take on former President Donald Trump ahead of an election that many believe is the most consequential in the country’s history. Even though politics is alleged to be boring, Michael Grinbaum reminds us the numbers aren’t that far south of the football Super Bowl, which draws some 110 million.

Trump immediately proclaimed victory for his apocalyptic warnings about America, saying his arguments persuaded 92 per cent of the audience. “We’re a failing nation in serious decline,” he said. Harris, he claimed, was going to lead America into a third World War. Experts largely disagreed, suggesting Harris successfully cornered her adversary on issues like abortion and healthcare, successfully illustrating the chaos and incoherence of his time in office.

Little of real substance, of course, emerges in such debates. The world already knew Trump wants Europe to pay more for its own defence, and a negotiated end to the war in Ukraine. For her part, Harris seeks to universalise health insurance and roll back restrictions on women’s reproductive rights.

For the kinds of political enthusiasts who enjoy cockfights and bear-baiting, though, there were plenty of low blows and abuse: The former President called Harris a Marxist who would pay for gender-reassignment surgery with public money while the Vice-President responded by describing him as a narcissist who easily seduced by flatterers.

Even though polls won’t give a clear idea of victory for days, the online prediction forum PredictIt showed those betting cash on the outcome thought Harris had improved her chances by two cents on the dollar. Trump is declining to commit to agreeing to another debate, but time to persuade voters is running out for both candidates. The state of North Carolina has already begun postal voting, and critical Pennsylvania will soon start.

The real question is, does the presidential debate really change the opinions of voters, as it famously did in 1960? The answer, in some key senses, is about the changing role of image in American politics, not about the ideas and policies of the candidates.

Also read: Kamala Harris attacks Donald Trump, puts him in defensive mode during presidential debate

The world of image

Fighting his way past the massed ranks of photographers and reporters, General Dwight Eisenhower returned to his hotel lobby from the Republican National Convention of 1952 and realised the world had changed. “When I entered my apartment,” Eisenhower later recalled, “I saw a marvel of communications that had never occurred to me. As I reached the door of my room, my eye was attracted to the television screen in the far corner. On it, startled, I saw myself moving through my own door.”

Television brought with it what the scholar David Blake has brilliantly described as a culture of “synthetic folksiness” to an America in the throes of its massive, post-Second World War boom. The Republican Party turned to a new advertising firm, Young & Rubicam, famous for Vitamin supplement advertising: A Marilyn Monroe lookalike coos from her unmade bed that she’s bought her boyfriend a 10-year supply, fondling the massive bottle as she seductively turns out the light.

Eisenhower, trained to give pithy, motivational speeches to men on the frontlines, was a natural recruit to this world. Young & Rubicam, as well as up-and-coming BBDO, were hired to craft an image for the candidate. The agencies shrewdly used glamour, recruiting celebrities to voice support for Eisenhower.

The wildly successful ‘I Like Ike’ jingles that carried Eisenhower to Washington remain as valuable cultural artefacts, which tell of an America deeply optimistic about its future—but also one willing to eradicate concerns over race and inequality from its cultural consciousness.

The age of celebrity

For their part, the Democrats also had a long line-up of celebrity supporters. Lauren Bacall was among the many stars smitten by Adlai Stevenson’s cerebral liberalism.“There were rich women, oh, very rich women, widowed or barely husbanded, brilliant women, philanthropists, scientists, diplomats, actresses, writers, women with titles of lesser nobility, and me, I guess,” Mercedes McCambridge wryly wrote.

Elvis Presley, the pop-culture god, threw his weight behind Stevenson, too, telling a reporter, “I don’t dig the intellectual bit, but I’m telling you, man, he knows the most.”

The re-match between Eisenhower and Stevenson came in 1956. This time around, David Blake notes, the changes in the television landscape were dramatic. “In 1952, 40 percent of American homes had a television set; by 1956, that number had almost doubled, to 76 percent,” he writes. Television had made its way into smaller cities and rural communities, and the number of broadcasting stations in the United States rose from 109 to 450.

Adlai Stevenson’s advisers, Ball argues, however, seemed oblivious to the fact that they were continually preempting America’s favourite shows for their 30-minute political programs. Their disregard earned the rancour of viewers across the country, one of whom wrote the Stevenson campaign: “I Love Lucy, I like Ike, drop dead.”

To make things worse, the 30-minute slots often aired at off-peak times, reaching only a tiny audience. There was little interest in using political advertising as a means to deliver a narrative rather than just an earnest political speech. Stevenson’s patent contempt for a medium that seemed to cast his ideas as part of a beauty pageant rather than a serious policy engagement didn’t help.

Viewers saw the disdain—and whatever their politics might have been, punished it.

Was it worth it?

Fishing off the Florida coast some weeks after that election-losing debate with Kennedy, his advisor Leonard Hall raised the question of why he’d agreed to one in the first place. Earlier in the campaign, Nixon had let it be known he despised the idea of a debate; he’d seen the competent Democrat Jerry Voorhis go down after agreeing to a shootout with an unknown lawyer. There was no answer to the question, Halberstram recorded: Likely, Nixon just didn’t want to be reviled as a coward.

In 1980, President Jimmy Carter—against his better judgment, again—agreed to a one-on-one against rival Ronald Reagan. Carter—and many others—considered the peanut farmer the more thoughtful, knowledgable politician. Reagan, however, brought an arsenal of self-deprecating humour that made Carter seem uptight and humourless.

Asked afterward if he had been nervous sharing the stage with the President of the United States, Reagan joked: “Not at all. I’ve been on the same stage with John Wayne.” There was, of course, a simple truth to this: In the age of celebrity, the President had, at most, a cameo role.

Agreeing to appear with Walter Mondale in 1984, President Reagan ensured the debates would become a permanent institution. Though so far ahead in the polls, there was no pressure on him to debate Mondale, Reagan believed his legitimacy and standing would be well-served by agreeing to participate. This became a template that has stood ever since.

The actual debate, John Self writes, are carefully choreographed, with lawyers and political advisors laying out terms, down to the numbers of cut-away images. The terms of the Harris-Trump debate, similarly, were hammered out down to the last detail, including a ban on the presence of a live audience, and rulers barring candidates from seeking advice from aides during breaks.

The time of the great presidential debates is likely coming to an end. The terse, gladiatorial possibilities of social media are becoming more important to shaping image than the formal structure of the debate, drawn as it is from university traditions that are themselves being consigned to the dustbin of history.

Praveen Swami is contributing editor at ThePrint. He tweets with @praveenswami. Views are personal.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)

Moderator was clearly biased towards Kamala Harris. Whether she won or lost is secondary. If she wins, this deep state meddling into small countries will continue, wars will continue, inflation will continue, woke shit will spill off further.

Librandus in the media don’t decide the fate of US presidential elections, they can only peddle fake narrative.