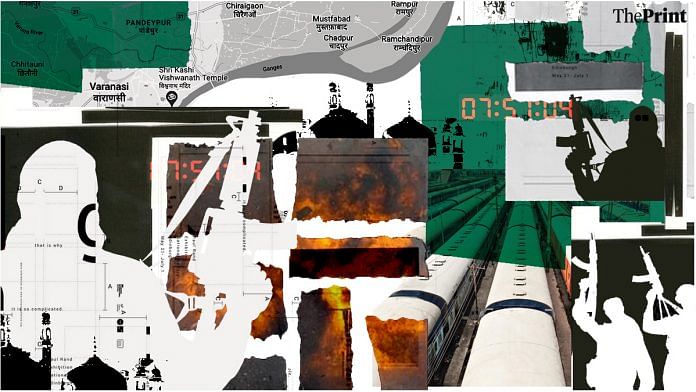

Flesh torn from human bodies; the remnants of wedding presents; little pools of blood; slippers abandoned as hundreds of panicked worshippers fled: the week before Holi, a macabre riot of colour spread out from the courtyard of the Sankat Mochan temple in Varanasi, etched into lanes by detonating ammonium nitrate and fuel oil, packed inside a pressure cooker. Fifteen minutes later, two more bombs went off at the railway station. Twenty-one people were killed, and dozens seriously injured.

This week, Indians have been grappling with the centuries-old contention over the Gyanvapi masjid. There’s a curious amnesia, though, about a more recent carnage in the city. Even though police in multiple states think they know exactly what happened that spring day in 2006—and at least some alleged perpetrators may actually be in prison—no effort is being made to initiate their prosecution.

As communal tensions flared across India in the wake of the bombing, police seemed to act. Local resident Mohammad Waliullah—a one-time student at the famous seminary in Deoband, and Imam at a mosque in Phulpur—was sentenced to ten years in prison for the possession of an assault rifle, grenades and plastic explosive. He wasn’t, however, convicted of the actual bombing. The Uttar Pradesh Police alleged Waliullah had handed over the explosives and pressure-cooker to three Bangladeshi terrorists who have never been identified.

Like in at least two other important Indian Mujahideen cases—a bombing in Delhi in 2005, and the 7/11 attacks on Mumbai’s train system in 2006—there is disturbing evidence to show police framed individuals unconnected to the case and refused to review new evidence as it came to light.

Also Read: Jihad in India is headed for rebirth. PFI knows riding the communal tiger is perilous

The man with the ringside view

The story rests on the testimony of a man waiting to be executed: Sadiq Israr Sheikh, one of the 38 men sentenced to death for setting off bombs across Ahmedabad in 2006. Throughout his youth, the Mumbai slum resident recalled in a conversation with the Gujarat Police—which, though videotaped, cannot by law be used as evidence in his criminal prosecution—that he had been “Communist-minded.” Then, “the pain that had taken root in my heart after the Babri Masjid episode got nurtured”.

A relative with links to organised crime, Mujahid Salim Azmi, introduced him to ganglord Asif Reza Khan. In February 2001, Sheikh travelled to Pakistan to train with the Lashkar-e-Taiba—and, on his return, had a ringside view of the genesis and rise of the jihadist networks, which later came to be called the Indian Mujahideen.

In November 2005, documents available with ThePrint record, Sheikh acquired six kilograms of ammonium-nitrate gel explosive, which he later told the National Investigation Agency (NIA) about. The explosive had been sent to Mumbai by the Indian Mujahideen’s fugitive southern-network chief, Riyaz Shahbandri. Indian Mujahideen operative Abu Rashid Ahmad picked it up and sent it to Azamgarh through Saraimir resident Shahnawaz Alam.

The improvised explosive devices, Sheikh said, were prepared at a rented Indian Mujahideen safe-house in Azamgarh’s Saraimir, using simple clock-based timers assembled by Arif Badr, an operative who had earlier trained with the Lashkar-e-Taiba in Pakistan. Atif Amin, the group’s commander, planted the pressure-cooker bombs at Sankat Mochan, along with Ariz Khan; the bombs planted at the railway station were put there by Asad Khan and Mohammad Sarwar Azmi, among others.

Andhra Pradesh Police counter-terrorism investigators arrived at the same conclusions. In a classified dossier, the police reported that reconnaissance for the attacks had been conducted in March 2016. The bombers, it said, travelled to Varanasi by bus on the morning of the bombings, planted the devices, and returned home to Saraimir.

Few of the men named survive. Atif Amin, the terrorist commander at the core of the Indian Mujahideen network, was killed in a shootout with the Delhi Police. Abu Rashid Ahmad last appeared in an Islamic State propaganda video and is thought to have been killed in Syria. Shahnawaz Alam is thought to have died in the siege of Mosul.

Ariz Khan, though, is in prison and is appealing against the death sentence he was awarded for his role in Batla House. Asad Khan is being prosecuted on terrorism charges linked to Indian Mujahideen attacks, and Mohammad Sarwar Azmi was arrested for his alleged role in a bombing in Jaipur. There’s plenty for investigators to go on—should someone start looking.

Also Read: Should Indian Muslims cling on to a non-mosque? Gyanvapi is a living monument of past wrongs

The usual suspects

Egregious disinterest in the truth has been a leitmotif of several similar cases. Five years ago, a court sentenced Kamal Sheikh, Faisal Ansari, Ehtesham Siddiqui, Naveed Khan and Asif Khan to death for their role in the bombing of Mumbai’s suburban train system. Seven other conspirators were handed down life sentences; one alleged perpetrator, Wahid Sheikh, was acquitted. Like in the Varanasi case, evidence has long existed to question if those convicted for the crime in fact carried it out.

In a statement to the Delhi Police’s Special Cell on 20 November 2008, for example, Sheikh said he and Atif Ameen had “prepared the bombs which were kept in three local trains in Mumbai in 2006.” To the NIA, similarly, Sheikh provided a granular account of how the explosives were made, and who planted them.

The NIA even stated in court, in a separate prosecution, that the 7/11 bombings were carried out “by Indian Mujahideen operatives including but not limited to Sadiq Sheikh, Bada Sajid [‘Big’ Sajid, a nickname for Mohammad Sajid], Atif Ameen and Abu Rashid”.

Law-enforcement officers have asked questions about key elements of the ATS’ 7/11 investigation—even questioning whether the Govandi chawl it had identified as a bomb factory had enough space to assemble seven explosive devices.

Former Director-General of Police Rakesh Maria, then leading the investigation into the Indian Mujahideen attacks by Mumbai’s Crime Branch, recorded a confessional statement from Sheikh, detailing his role in the 7/11 bombings. A second, supporting confessional statement was obtained from his associate, Arif Badruddin Sheikh.

The chargesheet the Crime Branch filed, indicting Sheikh, before 7/11 special judge YD Shinde, remains unopened more than a decade on. The appeals of the accused are pending.

Evidence showing that three Kashmiri men charged with carrying out blasts in New Delhi a day before Diwali in 2005—which the Indian Mujahideen took responsibility for—was similarly ignored. The Andhra Pradesh Police said that suspects had revealed, during interrogation, that the Delhi bombings had been carried out by Atif Amin—but the Delhi Police never followed up. Eventually, two Kashmiri men were acquitted, and one convicted of a terrorism charge unconnected to the bombing.

Like historical grievances, this depressing record suggests, terrorism cases aren’t primarily concerned with the truth of what happened. Instead, the terrorism issue has been used as a political tool, which serves to surrender communities and consolidate communal resentment. The manifest failure to deliver justice engendered conspiracy theories and toxic anger among both Muslims and Hindus, more lethal in the long-term than any bombs the Indian Mujahideen planted.

The real victim of the Varanasi bombing investigation has been the idea of justice.

The author is National Security Editor, ThePrint. He tweets @praveenswami. Views are personal.

(Edited by Srinjoy Dey)