Arjun Singh, who was born today, was an old-fashioned Gandhi family loyalist who believed he was denied the prime ministership twice, as Narasimha Rao and then Manmohan Singh were preferred, both of whom he considered lesser leaders than himself.

The first time I met Arjun Singh, he was dealing with a real crisis. It was in Bhopal a couple of days after the gas tragedy in December 1984. What struck me was his composure. He was cool, unruffled, and bantered with journalists. You could not miss the bonhomie between him and the Bhopal press corps. Arjun Singh, we all knew, had done more to improve the living standards of journalists in Madhya Pradesh, with government housing and other freebies, than anybody before or after him.

My first one-on-one conversation with him came the following summer. It was a short, half-hour Indian Airlines flight from Delhi to Chandigarh. He wouldn’t stop smiling as people lined up to congratulate him. He was on his way to take over as the new governor of Punjab, at a very young age of 55. The Punjab governorship then was not a job for retired people. The terror-hit state was constantly under President’s Rule. Rajiv Gandhi had just signed a peace accord with the respected and moderate Sikh leader, Sant Harchand Singh Longowal.

Arjun Singh, as Rajiv’s most trusted political lieutenant, had played a stellar role behind the scenes. No surprise then, that Rajiv trusted him to oversee its implementation. In fact, as I shook his hand while stepping out of that plane, I, somewhat naively, wished him a brilliant five years of governorship.

“Arrey bhai, young man, I do not know you very well. But do you want me to remember you as my friend or my enemy?” he asked me. He wanted to finish the job quickly, and get back to real, power politics.

His stint in Chandigarh, though, was longer and patchier than he would have wished. Within months of his arrival, separatists assassinated Longowal, exposing the limitations of the accord and the tenuous peace it had brought. Of course, Arjun Singh did not lose his cool. He asked his trusted aide, MP cadre IAS officer Sudeep Banerji, whom he had brought along from Bhopal, to get the pending applications of five senior-most journalists in Chandigarh for upgrading their government houses. His first executive act within minutes of that assassination was to upgrade them all, not by one but two levels.

Sure enough, many of the following morning’s stories talked not so much of his failure to protect his most valuable ward, but of how anguished he was that Longowal never listened to his entreaties to take his personal security more seriously.

Arjun Singh was too layered and fascinating a political figure to describe in one article. But one of the more interesting aspects of his personality was how seriously he took the media. Friend or foe, he never refused a journalist a favour. At the same time, he was never shy of raising that dreaded question: are you my friend or my enemy?

During his full stint as HRD minister in UPA-1, I was at odds with him as a columnist, as was the paper I edited. While we generally support the idea of caste-based reservations (though with important qualifications), we saw his move to thrust OBC reservations on the entire higher education system without any preparation as a too-clever-by-half ploy to unsettle Manmohan Singh, where it would be politically unwise for him to oppose that policy and impossible to implement immediately. It was in the course of that unrelentingly tough argument that I received an early morning phone call from him.

“I do not want to engage you in any long conversation,” he said, sort of deadpan, in clipped English. “I only called to tell you one thing.”

“Yes, Arjun Singhji?” I asked.

“It is just that had the man in whose name your paper is published (referring to Indian Express founder Ramnath Goenka), had he been alive today, you would not have lasted in your job for even one more week. I had that kind of relationship with him,” he said.

I was starting to tell him we were all so sorry that Ramnathji was no longer with us and that we all missed him greatly, but that he had left a formidable legacy and equally a successor, and that our freedoms were actually very secure with them. But he had no patience.

“I told you I do not want to enter into an argument with you,” he said and put the phone down. Gently; he did not bang it.

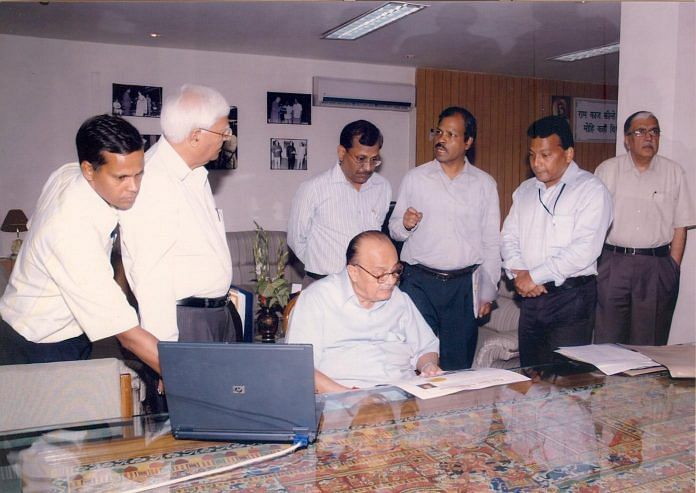

It is a tribute to our old-fashioned political tradition that in spite of so many run-ins, he always gave me time. My last long conversation with him was when he was recovering from a sudden attack of painful herpes zoster (shingles) on his face. He talked to me in half-recline, his face unshaven for days because of the herpes lesions. Of course he told me in detail where I had got my reading of politics, particularly politics of caste and poverty, all wrong. But then, maybe because he was distracted by pain, or just generous with me because I had come to look him up in this awfully distracting sickness, he began to speak expansively about himself, almost letting his guard down. Which, those who knew him better would tell you, was extremely rare.

“Why did I return to politics?” he asked. “Only because I discovered that within the Congress, even at senior-most levels, there were people who were in such a hurry to junk Rajiv Gandhi’s ideals.”

“You mean, Arjun Singhji,” I asked, “you are saving Rajiv Gandhi’s ideals from a party led by his own wife and son?”

“No, not that. It is just that none of the others was close enough to Rajiv to know what he really dreamed for India,” he said. Then he went on to describe the days when he, as chief minister of Madhya Pradesh, accompanied Rajiv deep into the countryside, “where we lay on cots in small inspection bungalows under star-filled skies and exchanged our ideas for the future of India”.

It was at this point that I saw his eyes moisten a bit. “One thing I will say about Rajiv,” he said. “His sense of patriotism was always palpable.”

Through exactly 25 years of knowing him, and both disagreeing and arguing with him intellectually, one thing I would never doubt was his loyalty to the Gandhi family. But that is what also made him so angry, bitter: he thought that his loyalty was not adequately rewarded, as the ultimate prize, the prime ministership, was denied to him not once but twice, as Narasimha Rao and then Manmohan Singh were preferred, both of whom he considered lesser leaders than himself.

Then, inside their respective cabinets, he tried to run circles around them, on his — and he presumed the Gandhi family’s — favourite issues: Rajiv’s assassination, secularism and social justice. He was mostly out-manoeuvred, though he succeeded in leaking and planting a twisted version of the Jain Commission report “implicating” the DMK in Rajiv’s assassination and bringing down the Deve Gowda-led coalition. Never mind that DMK later became a loyal and long-lasting partner of Congress—including in the UPA, where he served as HRD minister.

Yet, he failed to get rid of Rao or Manmohan Singh, politicians he did not consider half as sharp as himself, and it rankled with him. This, more than his many chronic health problems, angered him in his last years. But his political mind remained razor-sharp to his last day.

It’s been seven years today since he passed away and his party, his friends as well as detractors still miss him. So do we journalists, for whom he was a fine example of the traditional, accessible Congress politician, even if you mostly disagreed with him.

He was mass murderist as claim by many for fleeing the Anderson and absolute corrupt politician. He was never ever loyal to Gandhi family , Since he couldn’t win elections hence licking the Gandhi family shoes was his only option.

He was mass murderist and absolute corrupt politician. He was never ever loyal to Gandhi family , Since he couldn’t win elections hence licking the Gandhi family shoes was his only option.

Another senior Congressman, with much more impressive credentials for the top job, whom the family was unable to reward was Shri Pranab Mukherjee. The Gandhis must have a secret algorithm to help them make the choice.

Brilliant.