Before the Magadhan capital of Pataliputra – now known as Patna – rose to prominence as a political centre in ancient India, Rajgir held its place. It was the very first seat of power in Magadh under King Bimbisara c. 544 BCE. Surrounded by imposing mountains, Rajgir, also known as ‘Grivraja’, is revered in Buddhist and Jain scriptures and finds notable mention in the Mahabharata. These texts mention visits by Gautam Buddha and Mahavir to Rajgir, with Buddha residing at the Venuvana ‘forest monastery’ gifted to him by Bimbisara for many rainy seasons. The ‘Gridhra-Kuta’, also known as ‘vulture’s peak,’ was particularly special to Buddha – a cherished spot for meditation and delivering sermons. Rajgir also hosted the first Buddhist council within the Saptaparni Cave, highlighting the city’s importance in Buddhism.

Delving into the history and significance of Rajgir in shaping the politics and socio-cultural landscape of ancient Magadh could take pages. However, rediscovering the city today is proving to be as complex and detailed as its rich history. Over 12 archaeologists have undertaken extensive work at the site, exploring different facets of the settlements. Some have highlighted the importance of structures like Maniyar Math, a cylindrical stupa dated to the Gupta period (c.5 CE) that is used as a wishing well in 2024. Others have excavated Jarasandh ka Akhara, linked to King Jarasandha from the Mahabharata.

Archaeologists have also explored the Jivakamravana vihara, a monastery donated to the Buddhist sangha by Bimbisara’s doctor, Jivaka. Excavations were also conducted around the city’s fortification wall and the royal residential complex. Despite this meticulous work spanning two centuries, it seems like we’ve only scratched the surface. This is why a team from the Archaeological Survey of India Excavation Branch III, headed by Sujeet Nayan, began fresh investigations at Rajgir with new perspectives and agendas, aided by modern scientific analyses and technologies.

Although archaeology is known as the study of material remains unearthed from sites, it is actually the science of piecing together various aspects of human life, layer by layer, to reconstruct the past. Archaeology evolves with science. It adapts to new technologies and the changing times, continually adding layers to our understanding of the human past. Hence, it’s crucial to reassess sites and data collected in the past. Sites excavated decades ago – such as Rajgir, Hastinapur and Rakhigarhi – are being revisited, enriching our understanding and emphasising the importance of looking at these sites with fresh perspectives.

Also read: What caused the rise and fall of Harappan civilisation? Studies debunk role of ‘river culture’

Unveiling the mysteries of Rajgir: A journey through time

The challenges faced by explorers in the 1800s were different from those in the present. This is because the initial task then was identifying buried ruins mentioned in ancient texts and legends. This work was undertaken by Scottish surveyor Francis Buchanan in 1811 in Rajgir. He mapped out remains spread across the site in his report published in a journal by the Bihar and Orissa Research Society in 1825. Following Buchanan’s lead, a cadre of explorers, including Marshall M Kittoe, Alexander Cunningham, Joseph David Beglar, AM Broadley, and Aurel Stein, traversed Rajgir’s terrain, each leaving an indelible mark on its history. Cunningham, in particular, stands out for his comprehensive survey that laid the foundation for the Archaeological Survey of India, and mapped out political and trade centres with meticulous detail.

During Cunningham’s expeditions in 1861-62 and later in 1872, the legendary Maniyar Math emerged from the shadows, revealing its significance as a religious monument within Old Rajgir’s inner fortifications. This sacred shrine, mentioned in the Mahabharata, holds a storied past of blessings bestowed upon the city and its inhabitants. Yet, it was John Marshall’s excavation in 1905-06 that shed new light on Rajgir’s archaeological landscape.

Marshall undertook a major excavation at the site, which spelled important details about its archaeology and its chrono-cultural sequence. In this partial excavation at New Rajgir, the remains of secular buildings came to light on three levels – the highest level has a brick platform, low walls and a drain; the middle level was only 38 to 40 cm thick and the lowest was 2.5 m below the surface. In one of the dwelling houses was found a granary made of earthen rings and close to it an ancient well, made with wedge-shaped bricks. Among the important antiquities recovered were two clay tablets from c. 2– 1 century BC from a cell in the lowest level. Apart from these, one square copper punch-marked coin, six copper cast coins, a Gupta clay seal, a few terracotta seals, Buddhist sculptural fragments and some medieval coins were also found.

Further excavations by archaeologist T Bloch in the early 20th century revealed structural remains dating back to the Mauryan period, including those associated with Ajatasatru. In 1905-06, he excavated the mound by digging a trench from the east. He demolished a late 18th-century Jain shrine at the top and exposed a massive cylindrical brick structure, which can still be seen at the site. Several structural remains dating back to the Mauryan period, including those of a stupa, were discovered. Further investigation suggested that these remains might have belonged to an earlier structure associated with Ajatasatru. Additionally, various other stupa remains and Buddhist artefacts were unearthed in the vicinity of the site.

Adjacent to this stupa, Chinese Buddhist monk and traveller Hiuen-Tsang noted the presence of a 15.24-metre pillar topped by an elephant. Hiuen-Tsang mentioned observing the Ajatasatru Stupa to the east of Venuvana, a location that Indian archaeologist Amalananda Ghosh attempted to identify with a mound situated to the left of the modern road leading from New Rajgir to Old Rajgir. During Bloch’s excavations in the vicinity of Venuvana, numerous structural remains were also excavated, including those of stupas.

These pre-1947 surveys began with identifying major structures with historical references. The methodology was simply related to unearthing structures and acquiring antiquities. Although excavations by Marshall in the early 1900s improved the understanding of the site, it was only in the post-Independence era that archaeologists were willing to go beyond historiography and include scientific and non-scientific dating of the site and its materials.

Also read: 5,000-yr-old industrial hub—Binjor excavation shatters myths about ancient Indian manufacturing

Post-Independence endeavours

Following the dawn of Independence in 1947, the pursuit of unravelling Rajgir’s mysteries continued with renewed vigour. Amalananda Ghosh spearheaded the first investigation into Rajgir’s historical depths in the early 1950s, focusing on the excavation of the city’s fortification wall. Despite its modest scale, Ghosh’s endeavour shed light on the significance of the imposing cyclopean wall and underscored the ancient capital’s imperative for expansive fortifications. Subsequent scholars, including those undertaking excavations in 2024, further delved into this question.

In 1954, DR Patil embarked on an excavation venture at the Jivakarama Vihara, a monastery harking back to the era of Buddha and attributed to Jivaka, the royal physician of Bimbisara. Patil’s efforts unearthed an array of additional structures, including an elliptical edifice boasting two spacious halls with unconventional layouts. The excavation yielded artefacts such as crude redware pottery, iron nails, terracotta figurines, and copper coins. Concurrently, exploratory trenches near Maniyar Math sought to elucidate the stratigraphic sequence related to the introduction and disappearance of the Northern Black Polished Ware at Rajgir. Although the absence of substantial evidence initially suggested a stratigraphic hiatus, subsequent excavations proved otherwise.

From 1961 to 1962, ASI’s Raghubir Singh embarked on a renewed excavation campaign in New Rajgir. A significant trench laid across the southern defences uncovered three distinct periods, each with subdivisions. Period I was considered non-occupational with shapeless red ware sherds, whereas Period IIA had a mud rampart that was followed by the brick fortification of Period IIB. The top period – Period III – had stone foundations and ashy deposits with Northern Black Polished Ware, a terracotta figurine, a hoard of 14 punch-marked coins and fragments of steatite amulets. Carbon dating of samples from the pre-rampart deposit, which is Period I, provided valuable insights into the site’s chronology, with dates around 265 ± 105 and 260 ± 105 BCE.

In the 2000s, archaeologists expanded their focus beyond the confines of Old and New Rajgir, exploring contemporary settlements like Juafardih and excavating mounds situated between the valleys of Sonagiri and Udayagiri hills. These endeavours aimed to forge cohesive links between different settlements, enriching our understanding of Rajgir’s broader historical context.

Fresh excavations

In 2023, ASI Excavation Branch- III (Patna), led by Superintending Archaeologist Sujeet Nayan, proposed to excavate the city’s Inner fortification wall, Ajatashatru ka Qila Maidan, Garh and New Rajgir. According to Nayan, the main purpose of re-excavating New Rajgir is to procure Scientific dating for the Pre-Northern Black Polished/Northern Black Polished period. We are also trying to understand the settlement pattern/extension of the site with the nature of the rampart/fortification wall. The site has many spots of religious and historic importance like Jarasandh ka Akhada, Bimbisar’s jail, Saptaparni caves, and Sarpasaundik, Sitavana. For now, we are focusing more on the area surrounded by the five hills to understand the working pattern of those people (like artisans, craftspeople, villagers, farmers etc.) who were the goods and services providers to this huge location of great Magadha and were associated with its development in the bygone era.

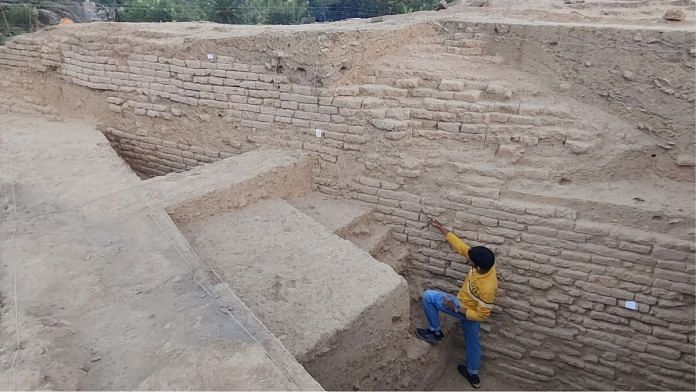

So far with this excavation, archaeologists have been able to reveal many brick structures, toiletry blocks, a ring-well, a kiln, furnaces, and rubble masonry brick walls made with uniform bricks. The dating of the said features and structures will be done on the basis of samples sent to the respective experts and government agencies like Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences, Lucknow. The most interesting and outstanding finding is the massive and gigantic burnt brick fortification wall below the rubble stone masonry wall.

According to Nayan, when they looked at the antiquities of New Rajgir, they recovered inscribed sealings of the Maurya and Gupta periods, bone tools, iron implements, and beads made of semi-precious stones. In terms of ceramic assemblage at the site, the excavators have revealed Red Ware, Red Slipped Ware, Red and Black Ware, Painted Ware, Black Slipped Ware, Grey Ware, NBP and its associated wares etc. Many intact dishes and pots are also showcased in the temporary on-site exhibition gallery for the visitors.

Despite multiple excavations, the archaeological story of the city of Rajgir is still not clear. Nayan and his team are hoping that this excavation will soon turn into a full-term government funded project. According to them, Rajgir is not an ordinary site. It has a mythological, pre-historic as well as historic significance. Rajgir was the capital of Magadh, the great Mahajanapada of ancient India. It witnessed the reign of many dynasties like the Haryankas, Nandas, and Mauryas. The so-called mythological and historical legacy of Rajgir continues from the time of Jarasandh (a powerful king of Magadh during the Mahabharata period) to Ajatshatru (491-459 BCE) and Udayin (459-443 BCE) and goes on till the medieval period.

Considering the elaborate history of this city, excavators hope for expansive and multi-dimensional archaeological research extending to its neighbourhood.

Apart from archaeological investigations, the ASI is also trying to promote tourism at the first capital of Magadh. It is interesting to note that Rajgir is located between the route of Nalanda and Bodh Gaya – the two UNESCO World Heritage sites – which makes it a great centre of attraction. It also has immense potential to help develop a Buddhist circuit. Therefore, the aim of these excavations is to not only help enrich our knowledge about the past, but also help create a cultural, religious, and eco-friendly hub of international trade.

This article has been updated.

Disha Ahluwalia is an archaeologist and junior research fellow at the Indian Council Of Historical Research. She tweets @ahluwaliadisha. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)