The global events of the last one year, especially during the Russia-Ukraine war, have again shown the importance of food security to the world. It is critical for India too as it has to provide food to a large population of about 1.39 billion people. Punjab and Haryana continue to be the leading states in contributing to central pool stocks of food grains. The two states earned a lot of flak during the farmers’ agitation for demanding continuation of the existing system of APMCs and Minimum Support Price operations. Like the rabi marketing season, in the current kharif marketing season 2022-23 (October – September) also, the two states have provided comfort to the Union government.

Paddy crop 2022

Due to delayed monsoon and its erratic monthly spread, both area and yield of paddy may have suffered in many states.

At all India level, area under paddy was about 20 lakh hectares lower than last year (403 lakh hectares in 2022 as compared to 423 lakh hectares in 2021). The sown area was lower in Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Andhra Pradesh.

Impact of erratic monsoon is likely to reduce rice production. As per the government’s first advance estimates, India’s kharif rice production is likely to be about seven million metric tonnes (MMTs) lower than last year. It was about 112 MMTs in 2021-22 and is estimated to be about 105 MMTs this year. India also produces rice in rabi season, but its (the season’s) contribution to the country’s annual rice production is only about 15 per cent. So, making up for this loss of production may not be possible.

Also read: PM Kisan’s direct transfers can help food distribution. But there are four challenges

Paddy procurement 2022

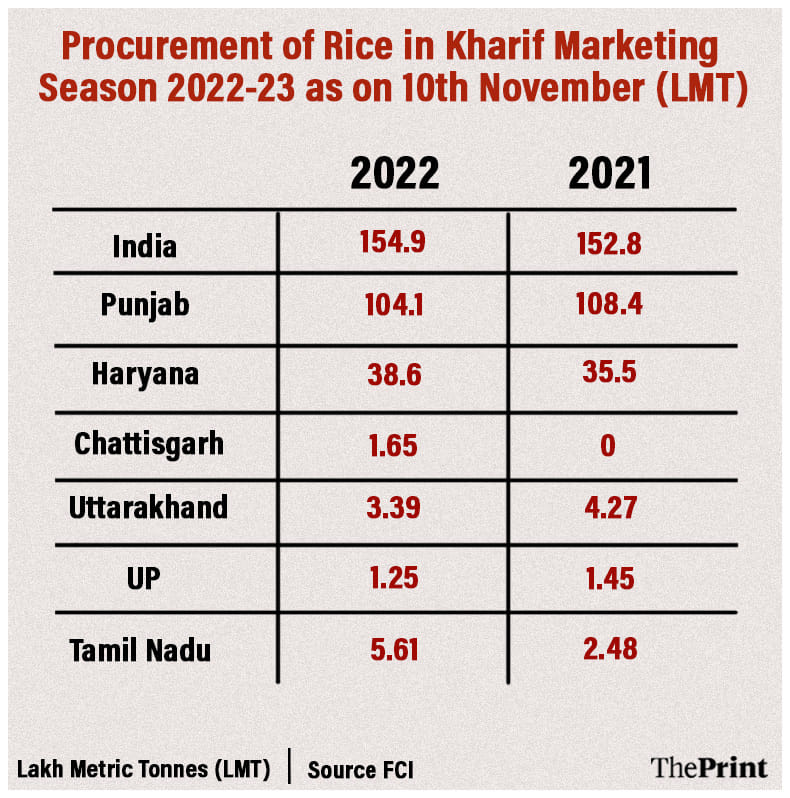

Lower production will also pull down procurement of rice. As of 10 November, 231.28 lakh metric tonnes of paddy has been procured. This will deliver about 154.9 LMT of rice (one quintal of paddy gives about 67 kg of rice). Last year, on this date, the procurement in terms of rice was 152.8 LMT.

In 2021-22, 43.91 LMT of rice was procured in UP. This year, the estimated procurement in the state is 40 LMT. Both east and west UP received lower rainfall, especially in July and August. By 2 September, the rainfall was deficient by 44 per cent in both east and west UP. Therefore, the paddy production is expected to be lower than last year. It is therefore rather unlikely that UP will be able to procure 40 LMT of rice.

Role of Haryana and Punjab

These two states have been at the forefront of India’s food security. This year also, their contribution is substantial.

As of 10 November, Haryana has procured 38.6 LMT of rice this kharif Marketing Season against last year’s 35.5 LMT. Punjab has procured 104.1 LMT, which is about 4.3 LMT less than 108.4 LMT procured last year. Taken together, the two states account for 92 per cent of rice procured so far.

The procurement of paddy in these two states is almost over by the end of November as the APMC system is strong and streamlined. In other states, where APMCs are not that effective, like UP and Bihar (APMCs do not exist), the arrival of paddy continues for several months beyond November.

It must be recalled that wheat production this year was adversely impacted due to unusually warm weather in March and April 2022. Government estimates still show the production at 106 Million MTs, while the trade estimates the wheat production between 95-100 Million MTs. Due to a smaller wheat crop, the government could not procure the required quantity of wheat this year. In fact, (i) the wheat procurement was only 187.9 LMT (Lakh Metric Tonnes), down from 433.4 LMT in the previous year; and (ii) wheat stocks in central pool are at their 14-year low levels. Punjab (96.45 LMT) and Haryana (41.86 LMT) were the most important contributors of wheat procured this year. The two states accounted for 73.6 per cent of wheat procured. Both Punjab and Haryana continue to play the role of dominant yet stable and consistent suppliers of these grains to the central pool.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, the government could provide additional food grains, free of cost, under the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY) only due to the excessive procurement of wheat and rice in the previous four years.

Also read: What’s common between Modi & Manmohan govt on agriculture? Distrust of futures markets

Paddy/rice outlook 2022-23

With a lower kharif crop, will production of paddy in rabi crop be able to cover some of the production lost in kharif crop due to lower rainfall?

Paddy is grown in rabi crop season in Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Telangana and West Bengal. Several state governments are pushing for diversification from paddy to less water-guzzling crops in kharif and rabi seasons. Haryana, Chhattisgarh, Telangana have taken lead in this direction and several incentives have been announced for farmers who move away from paddy to alternative crops. Chhattisgarh is offering assured procurement of arhar, moong and urad at MSP and has declared zero acreage for its upcoming rabi paddy crop. If these incentives are successful in reducing the area under rabi paddy, the production of rabi rice could be lower than normal.

Over-reliance on wheat and rice

Since the Public Distribution System is continuing in its present form and there is no roadmap to move to direct benefit transfer of food subsidy, the Union government will continue to depend on procurement of wheat and rice at MSP.

Many states, as mentioned before, are making efforts to encourage production and procurement of pulses like arhar, moong and urad. These states can undertake such procurement under the government’s Price Support Scheme (PSS) but they are only allowed to procure 25 per cent of their production. In case of nutri-cereals, they are required to distribute the procured quantity within their state. This is the reason for their reluctance to procure pulses, oilseeds and nutri-cereals, beyond the quantity permitted by the government under PSS. In the past, Nafed (National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation of India Ltd) was the nodal agency for procurement of pulses and oilseeds under PSS and it incurred losses.

Ideally, the market should support MSP for these crops so that procurement by the government agencies is not required but year after year we find that prices go below MSP during the peak arrival season.

Price incentives are critical for farmers and if these incentives continue to work only for rice and wheat, diversification to less water consuming crops will not be found attractive by the farmers. In the era of climate change, if Punjab and Haryana do not produce enough surplus of rice and wheat, the food security for basic staples itself may be under threat.

Hussain is a former Union Agriculture Secretary. Saini is an economist. They are promoters of Arcus Policy Research. Views are personal.

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)