Twenty-two-year-old Mahsa Amini is not the first victim of Iran’s obsession with morality, nor is this the first time the country is emerging in protest against the imposition of the hijab. With its guarded, nuanced and minimalistic portrayals, Iranian cinema—known as one of the world’s most exciting and path-breaking film industries—has been sloughing at the edges of this bitterly repressive regime for years. From Abbas Kiarostami to Rakshan Bani-Etemad and Mania Akbari, Iranian filmmakers have been leading a quiet fight for liberation while adhering to their nation’s strict hijab laws.

For the filmmakers, it has been a carefully choreographed waltz of rebellion against the stifling hijab rules, playing with image and imagination and testing the limits of what they can get away with.

Yet, as veiled as they are in their treatment of the subject, contemporary Iranian directors have never shied away from circumventing religious fatwas and offering social critique without disrespecting the hijab—or their art.

“I think it is one of Iran’s major exports: in addition to pistachio nuts, carpets, oil, now, there is cinema,” Kiarostami told a Parisian journalist in the early 1990s. After the revolution of 1979 deposed Mohammed Reza Pahlavi—the modern, forward-thinking Shah of Iran whose reign saw women flourish sans headscarves—two forms of filmmaking came to dominate modern Iranian culture. Populist Cinema, which emphasised and glorified ‘Islamic values’, and Quality Cinema, which questioned, assessed and critiqued these values while still being in line with the country’s mandatory hijab laws.

Also read: The many shades of grey in Iran’s hijab war show it’s not just personal freedom vs theocracy

Hijab in Iranian pop culture

As Iranian cinema switched between these crucial phases, so did its complex relationship with the hijab. Between 1979 and 1981, earlier films from a relatively modern and liberal period in Iranian history were ‘heavily edited’ as per the country’s new hijab-abiding censorship diktats. As a result, Iran became obsessed with keeping its women and revolutionary ideas of love in purdah. Women disappeared from big screens and action films such as Z, State of Siege, Battle of Algiers, and Battle of Chile came to dominate. These movies focused more on concepts of revolution and wry military hardware and not on the trademark aesthetic that Iranian films are now known for, writes author Hamid Naficy.

Children’s films developed as a separate dominating genre. This included Kiarostami’s educational short Toothache (1980), which taught children the importance of dental hygiene, followed by Where is My Friend’s House (1986), which showed a young boy struggling to return his classmate’s notebook after accidentally bringing it home. They were perfectly in line with Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s diktats on using “cinema for education”. But, as expected, women were reduced to background actors, rarely coming to the fore and driving the narrative.

Only from the late-1980s were hijab-clad women observed on screens, albeit in unrealistic situations. Take Jafar Panahi’s critically acclaimed The White Balloon (1995). It tells the story of a little girl who loses the money she has saved to buy a much-coveted goldfish. Seven-year-old protagonist Razieh (Aida Mohammadkhani) is seen donning a crisp white Hijab, even at home. This is in stark contrast to Iranian law, which allows women to keep their heads bare within the four walls of their homes. However, for the film to be screened, it was important for Panahi to conceive of logical situations where the hijab would seem appropriate because women are not allowed to show hair, skin, or even the contours of their body on screen. Where is My Friend’s House depicted women in a similar manner, as protagonist Ahmed (Babek Ahmed Poor)’s mother keeps her head covered even while tending to her household chores. Kiarostami, however, makes it look realistic by fashioning the headscarf as a messy turban meant to keep stray hair out of the way.

“People are thus motivated to search for hidden, inner meanings in all they see, hear, and receive in their daily interactions with others, while trying to conceal their own intentions,” writes Naficy in the 2000 edition of international quarterly Social Research, while commenting on Iran’s complex but often artful relationship with “veiling and unveiling” on screen.

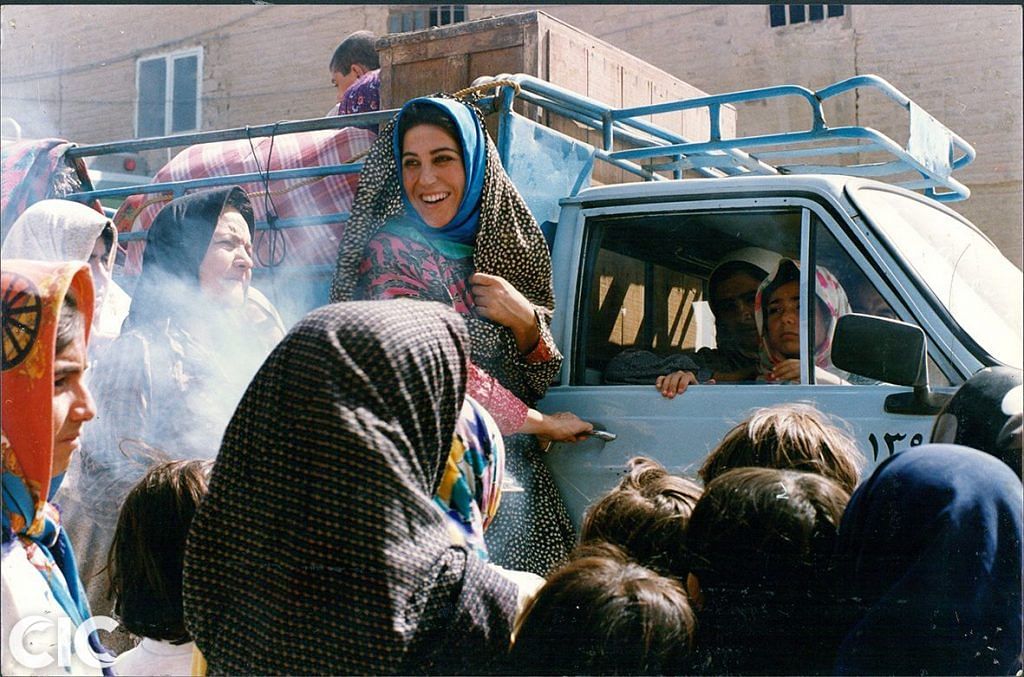

From Faryal Behzad to Rakshan Bani-Etemad, as more female directors began to enter the Iranian film space in the 1990s, the hijab began to acquire new meaning. Filmmakers like Bani-Etemad—also known as the first lady of Iranian cinema—pioneered this movement by rooting their stories in ‘social realism.’ According to Naficy, in her 1994 film The Blue–Veiled—a tale of romantic love between an old farmer and a young peasant woman who is always clad in a blue hijab—Bani-Etemad implies lovemaking by showing sensuous close-up shots of the woman’s bare feet. This way, she bends modesty rules but doesn’t outrightly break them. The gorgeous blue veil is not a meaningless motif. Instead, it signifies suppressed desire and a woman’s right to love, ultimately serving as a powerful social commentary on Iran’s repressive culture.

Kiarostami moves a step ahead with his path-breaking film Ten (2002), where a female cab driver (Mania Akbari) ferries 10 women passengers from different walks of life, their stories a criticism of life in Iran.

Interestingly, the entire film was shot with just two handheld cameras. The women and their differing outlooks are conveyed through their style of donning the hijab. For instance, the self-reliant and ‘modern’ Mania wears hers loosely around her neck, completing the look with fashionable sunglasses and colourful rings around her fingers. At the same time, one of her more conservative passengers wraps her scarf tightly, conveying varying degrees of empowerment. Mania Akbari went on to direct 10+4, or Dah Be Alaveh Chahar (2007), a powerful sequel to Ten, where she explores “the sensation of living with both life and death.” Akbari plays a breast cancer patient who loses her hair—and her hijab—while healing from the disease in an orthodox society. By baring her bald head, Akbari almost brilliantly bends Iranian hijab laws—portraying, questioning, and protesting in the same breath.

“I’m a good thief, stealing bits and moments of life, and offering it back to life with an added meaning,” Akbari told Raising Films in a 2018 interview.

Also read: ‘We will fight, we will die’ — nationwide protests in Iran pile pressure on state

Bollywood under my burkha

Move to neighbouring Bollywood, and the hijab morphs into something glamorous—a marker of textbook Muslim grace and humility, as well as thrill and mystery. For instance, Priyanka Chopra in Saat Khoon Maaf (2011) dons a burkha while enjoying qawwali and shayari with her on-screen husband Irrfan Khan. Or take Nauheed Cyrusi in Anwar (2007), whose burkha-clad avatar from the evergreen song Maula Mere has come to define a stereotypical Muslim woman in India, both beautiful and intriguing thanks to her purdah.

However, to say that its depiction has not evolved with time would be an understatement. Alia Bhatt in Raazi (2018) and Gully Boy (2019) come to mind. In Raazi, the veil masks mysterious (and quite literally undercover) Indian spy Sehmat, while in Gully Boy, it shows a fiercely independent and spunky Safina who is unafraid to express her religious identity. The veil also acquires different meanings in Lipstick Under My Burkha (2016). Shireen Aslam (Konkana Sen Sharma)’s burkha shows her shedding her repressed identity to embrace her freedom and sexuality. In contrast, Rehana Abidi (Plabita Borthakur)’s burkha helps her lead a comfortable dual life, which, as we know, doesn’t last for long. Much like Iranian films, it serves as a commentary on the status of women in India, showing how the hijab that often suppresses can also empower.

Views are personal.

This article is part of a series called Beyond the Reel. You can read all the articles here.