From Hindu Mahasabha bases in India to major theatrical spaces in London, the debate surrounding Nathuram Godse and his legacy is very much alive. It gains traction every year around the time he assassinated MK Gandhi, or when he was hanged 75 years ago on 15 November.

Some vocal groups wish to rehabilitate Gandhi’s killer, recalibrating his image from murderer to patriot. By way of commemoration, Hindu Mahasabha leaders shot an effigy of Gandhi on 30 January 2019, the 71st anniversary of his assassination. Three years earlier, members of the organisation had placed garlands on a portrait of Godse in Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh.

Chennai-based playwright Anupama Chandrasekhar’s The Father and the Assassin—which ran at the National Theatre in London between September and October 2023—is one of the many recent additions to the debate. It was nominated for Best Play at the Evening Standard Theatre Awards in 2022, and follows Chandrasekhar’s 2019 play, When the Crows Visit, which was based on the events of the 2012 Nirbhaya case.

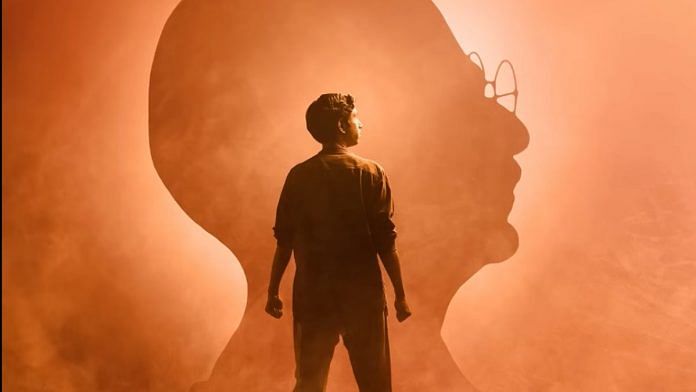

At the beginning of the play, Godse (played by Hiran Abeysekara) directly addresses the audience, standing barefoot on a sparse, dark stage. He suggests that by the end of the play, he may not seem so evil. This isn’t an effort on the part of Chandrasekhar to redeem Godse — but to enter into the mind of an assassin.

The play’s crux is that in order to comprehend Godse’s actions, it is necessary to uncover his experiences and perspective. “What are you staring at? Have you never seen a murderer before?” he asks the audience.

Most interestingly, the dynamics of gender and family are front and centre in this unique treatment of well-trodden ground.

Also Read: Godse was ‘yearning’ for Savarkar’s support in Gandhi murder trial court. But it never came

The complications of gender

Godse had an unusual childhood, to say the least. His mother had given birth to three boys before him, but all died as infants. Convinced that all boys in the family were cursed, the parents decided that their next child would be raised as a girl, whatever their biological sex.

As such, Godse was brought up believing he was a girl. He also served as an oracle for the goddess Durga, which brought visitors to the family home, hoping to communicate with the deity. The play weaves these aspects of his childhood into the opening act. At one point, Godse innocently asks his mother if he might be allowed to stand up to urinate like his father.

In Godse’s very name, there was the performance of the female. His parents called him Nathu, which means nose ring, a piece of jewellery traditionally worn only by women. And as his birth name was Ramachandra, he became Nathuram—the Ram who wore a Nath.

Watching the play, one cannot help but wonder if Godse’s confusion surrounding his gender during childhood impacted his politics as an adult. Did Godse feel like a “real” boy once he found out the truth? Perhaps he felt that the first decade of his life undermined his status as a man.

In later scenes of the play, Godse involuntarily imagines conversations with his childhood friend Vimala (played by Aysha Kala), in which she disdainfully calls him “Nose Ring”. Do these scenes imply that the adult Godse still felt unable to fulfil the expectations of masculinity? Did the fear that some people still saw him as feminine lead him to try and assert strength, notionally a masculine quality, via his Hindu nationalist politics? The play deliberately does not provide conclusive answers, rather it asks probing questions for the audience to consider.

Godse thought that Gandhi was effeminate, and, in turn, weak. By contrast, he saw himself and his nationalist politics as masculine and strong. The British colonisers saw Indian men as effeminate, and in turn, deserving of subordination and in need of tutelage. Scholar Mrinalini Sinha’s seminal text from 1995, Colonial Masculinity: The “Mainly Englishman” and the “Effeminate Bengali” in the Late Nineteenth Century, famously dealt with this subject. It is somewhat ironic that Godse, the nationalist, imbibed the colonialist discourse in his assessment of Gandhi.

Also read: Long before Gandhi, Godse pulled out a knife to stab Mahasabha chief for allying with Nehru

False fathers

The play is also largely about fatherhood. Early on, a scene shows a chance encounter between Gandhi and Godse: the former reveals to the child that he is, in fact, a boy. This is probably a fictitious encounter, but through this scene, the play suggests that it is Gandhi who enables Godse to become a man for the first time.

In this way, Godse sees the nationalist leader as a surrogate father. Where his biological father had lied to him, his surrogate father was truthful.

As a child and young adult, Godse is even shown to be an ardent supporter of Gandhi. As time progresses, Chandrasekhar shows how Godse feels more and more let down by him. True to the historical record, the play shows how Godse came to see Gandhi’s anti-communal politics as anti-Hindu.

Convinced that his hero has embraced Muslims at the expense of Hindus, Godse feels both individually and communally betrayed. He perceives himself as a special representative of the Hindu nation, internalising the communal rejection. In his eyes, Gandhi is no longer the ‘father of the nation’, just as he is no longer his surrogate father.

It appears that Chandrasekhar deliberately didn’t write a play about Godse’s trial, the audience doesn’t even see the judicial proceedings. However, pondering the court action for a moment does contextualise the play’s focus on fatherhood.

On the stand, Godse declared, “Gandhiji himself was the greatest supporter and advocate of Pakistan”. The full speech was published in 1989 in May it Please Your Honour, and again in 1993 in Why I Assassinated Mahatma Gandhi. He believed that Gandhi and Congress consistently pandered to Muslims, and Partition was the apotheosis of this pattern. Turning to the lexicon of family, the disgruntled nationalist called Gandhi the “Father of Pakistan”.

This was characteristic of the political culture at the time. Mohammad Ali Jinnah, a lawyer by training, had drawn on testamentary frameworks to formulate an argument in favour of Pakistan. His idea was that the colonial father was dying, and his two sons were fighting over the inheritance. As Jinnah saw it, the Hindu son and the Muslim son should have their own properties by splitting up the colonial inheritance.

During his trial, Godse explained that as a son of ‘Mother India’ who understood his duties, he had no choice but to kill Gandhi. The assassination thus becomes a nationalistic act by a son endeavouring to protect and serve his mother.

Back in the play, describing the borders drawn for Partition, Godse jokes with the mostly British and British Indian audience that Mountbatten was looking for a hard Brexit when separating India and Pakistan. Many of those who voted for Brexit were individuals who felt that their voices had been muted by elites and cosmopolitan globalists. In India, and many countries around the world, the nationalist message can resonate the loudest with those who believe they have been passed over.

Chandrasekhar respects the audience too much to pontificate and dictate what their opinion should be, and so, throughout the play, deeply significant questions are raised with a light touch.

Also read: When Gandhi murder investigator got on the same taxi Godse and others took

Resonance with the politics of today

The second half of the play has numerous scenes set in Ratnagiri, Maharashtra, in which Godse implores VD Savarkar to train him as his apprentice. Finally, the Hindu nationalism stalwart agrees to educate Godse. These fictionalised scenes cleverly act out Godse’s movement toward Savarkar’s politics.

In an interview on The Evening Standard Theatre Podcast in September 2023, Paul Bazely, who plays Gandhi in the play, explained that to have relevance, historical plays must say something about the current times. For Bazely, the themes of extremism, polarisation, and violence that characterise the play are issues that society currently faces.

Terrorists and mass shooters are quite often individuals who feel unnoticed and overlooked by society. Deeply alienated from the world, these troubled individuals can be radicalised and pushed toward extremist, violent ideologies.

Toward the end of the play, Godse again speaks directly to the audience. It appears that he is at his most frank now: he admits his feeling of ordinariness and invisibility. After he “became” a boy, he lost contact with the goddess Durga and concomitantly the feeling he was special.

The play implies that above all, Godse wanted to be someone — he saw himself as a martyr and wanted to be treated as such. Interestingly, as we see in May it Please Your Honour, Godse acknowledged during the trial that “the day on which I decided to remove Gandhiji from the political stage, it was clear to me that personally I shall be lost to everything”.

He would become an outcast and the most hated man in the country, but at least he would be known.

Views are personal.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)