What do India’s Sikhs have to gain by supporting Muslims? Why do Sikhs even care to protest against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, when their citizenship in India is guaranteed?

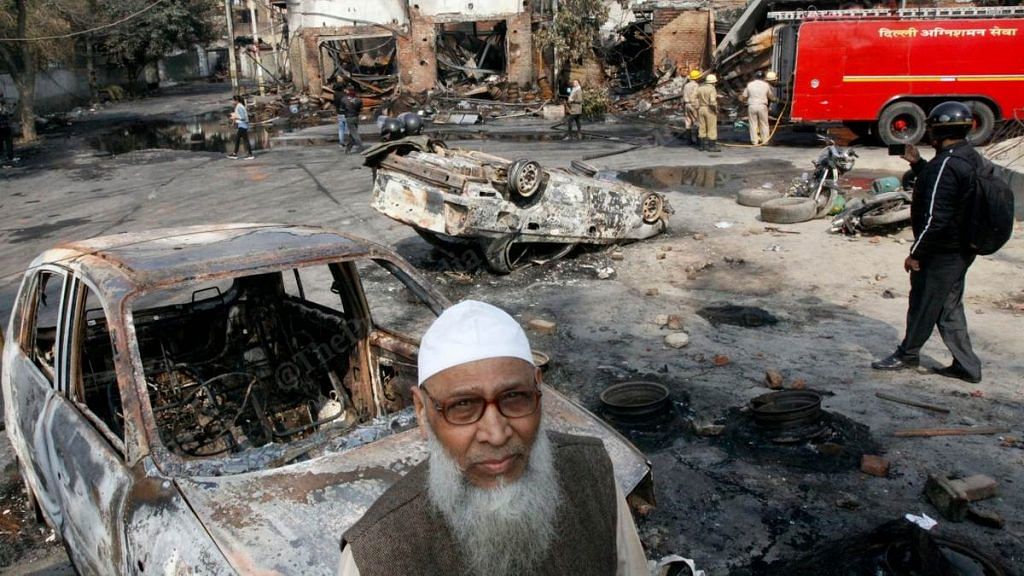

Many asked these questions after two Sikhs, Mohinder Singh and his son Inderjit Singh used their trusty Bullet bike and Scooty to transport over 60 Muslims to safety during the northeast Delhi riots. In the same city, Akal Takht jathedar constituted a six-member committee to go on the ground and get a first-hand account of what happened in the riots and set up food counters for displaced people.

Even at the anti-CAA protests in Shaheen Bagh, Sikhs and Muslims prepared langar together. There were videos of Sikh and Muslim men exchanging their headdresses and clicking selfies together.

Naturally, these raised several questions about the Sikh community’s solidarity with India’s Muslims. To them, I say one thing: we’re united by grief. And we don’t want to precipitate another partition of the minds.

Also read: When Delhi rioted, Sardar Patel busted fake news and wanted a Hindu newspaper banned

Remembering without hating

When I was a child, my mother used to boast of the havelis her family owned in Pakistan. She told me about my Sikh grandmother, the jewellery she was unable to wear and the train she was never able to take back.

On some days, she recalled the sacks of sand my grandmother had to hide behind during train journeys. My grandfather often joked about how he is well-versed in Urdu but has no friends to talk to in that language anymore.

I once asked one of my uncles why he didn’t wear a turban. I still remember his very matter-of-fact answer: “I had to cut my hair during 1984.”

After years of pondering on all my relatives’ seemingly detached narrations of gruesome incidents, I understood exactly what my family wanted to convey. To remember, but without the hatred.

Also read: What data and history of India and its capital tell us about Delhi’s riots

Futility of hate

India’s Partition uprooted families, disrupted lives, communalised harmonious neighbourhoods. Sikh families, apart from Bengalis, were the worst affected by its aftermath and unarguably so. My ancestors picked themselves up only to fall back again in 1984. We faced extreme brutality at the hands of our fellow countrymen after former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was assassinated by her trusted Sikh bodyguards.

This is not to say that there wasn’t a backlash from the Sikh community. The Khalistani terror movement ended up killing more of our own. Through the course of time, we were harshly taught the futility of hatred.

Also read: Why Delhi riots are different — what ThePrint’s 13 reporters, photojournalists saw on ground

You will not have our hate

When I asked my family about why they don’t feel vengeful of their violent past, there were a scurry of replies: “We forgive and don’t forget?”; “It’s our sense of humour?”; “Hatred doesn’t help anyone”; “Our Gurus taught us self-defence?”

The Dasam Granth, whose compositions are attributed to Guru Gobind Singh states: “When all peaceful methods have failed to bring justice, it is righteous to draw the sword”. Moreover, it asserts that Sikhs must never be the ones to draw the sword first.

Our collective history has been witness to violence, disruption, Partition, detachment, harassment. At the same time, asking one generation to pay for the faults of another is simply nonsensical at best and unacceptable at worst. And if history ever teaches you a lesson, it’s that you never repeat it.