In early 2023, the Archaeological Survey of India resumed excavations at Purana Qila in the heart of New Delhi. Archaeologist Vasant Sawarkar had dug new trenches there in 2013-14 and 2017-18, following the first excavation led by BB Lal in 1954 and again in 1969-73.

The previous excavations traced cultural material from the Medieval period to Gupta period, going as far back as the Mauryan Empire. The aim of this re-excavation, therefore, was to open the trenches to encourage tourism and public engagement. However, from the standpoint of an archaeologist, the goal (other than conserving trenches and excavating new evidence) is also to find a piece of evidence much older than the Mauryan Empire to eliminate the possibility of a “Dark Age” in Indian history and become a cultural marker.

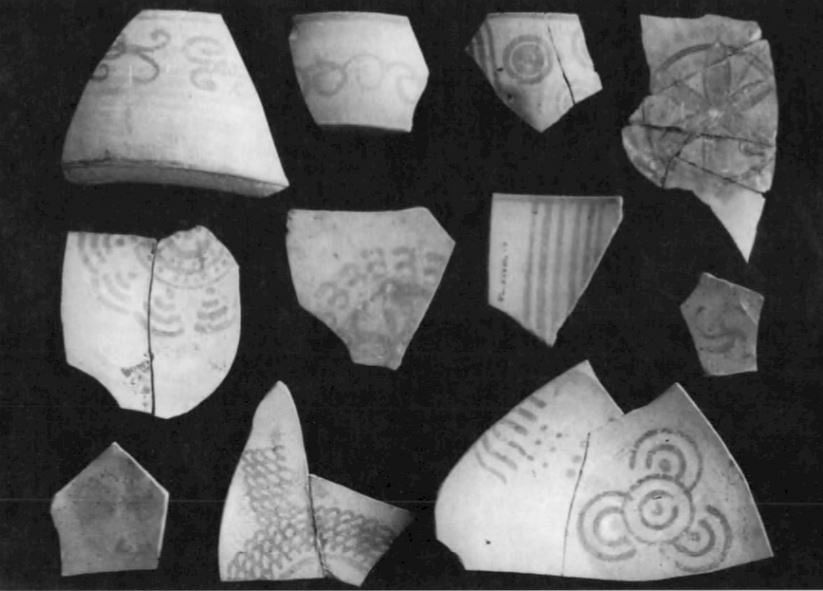

One evidence, a soft grey pottery with beautifully painted motifs that was discovered at Ahichchhatra in Bareilly in 1944, was formally added to the chronology of the subcontinent as a distinct culture in the 1950s, following the excavation of Hastinapur. But it could not be traced adequately at Purana Qila during all the investigations.

Seventy years since Hastinapur excavation, this single evidence, known as the Painted Grey Ware, still evokes interest in archaeologists and curiosity among people. But why?

What is this Painted Grey Ware? And why are people and archaeologists obsessed with it? And how does a ceramic type become a cultural marker?

Also read: Why classifying societies on the basis of ceramics isn’t the best approach to know histories

Painted Grey Ware

Put simply, it’s a soft grey pottery with painted patterns. The exquisite fabric, firing, and finish are what make Painted Grey Ware special. Although the shade of grey varies, this ware can be identified by its texture and consistently well-fired section.

Painted Grey Ware (PGW) has a signature fine fabric, which is achieved only by preparing a well-levigated clay dough. The potter chooses a particular time of clay and mixes it with sand but in the correct proportion. Then the mix is sieved until micro granules are removed. Once the mix is free of any impurities, it is grinded with water and then kneaded into a smooth paste. This is done carefully to avoid formation of air bubbles. In some cases, the clay is also kept aside for a few hours or days before it’s thrown on the potter’s wheel. After the potter achieves the desired texture of the clay, the pots are made and prepared for firing.

The website of University of Manitoba in Canada describes the process thus: “The colour of pottery, which gives it its name, is affected by the method in which it is fired; as the iron oxide content in clay will react to the amount of oxygen inside the kiln. For example, by firing in an oxidising or smoke free atmosphere, the iron content will produce a red surface; a reducing or smoky atmosphere will produce a black finish.” In both cases, if the temperature and the level of oxygen is constant, then the colour of the pot and its texture will be even. The section can tell you that. In the case of PGW, the reduction technique is used. But to get a grey surface with the reduction technique is highly difficult.

One had to really master the kilning technique. If the temperature is increased or if the reduced atmosphere in the kiln is not conducive, then there are chances that the pot turns black. One has to achieve a particular level of reducing or smoking atmosphere with some percentage of oxygen to get even smooth soft grey finish. The tradition of grey pottery has existed since the neolithic period. But a uniform grey colour with such fine fabric was never found before. This made PGW an example of advanced kilning technique. The authors of this ware moved to a level up from existing techniques.

Many experimental studies are done in order to understand the mysteries of PGW. Prof KTM Hedge’s work on PGW is important. He tried to analyse the chemical composition of clay as well as pigments used for painting. According to him, the PGW was indeed baked in reduced atmosphere. Reduction of a thinly distributed small percentage of iron oxide in the clay helped in achieving grey colour. GG Majumdar (1994) undertook the similar experiment and suggested that besides reducing conditions, iron oxide in the clay is used for the purpose of getting soft grey colour. The thin section study of the pottery also shows a high level of purity in clay with minor inclusion of quartz.

Also read: BB Lal—first archaeologist who showed proof that Ayodhya was no mythology

From humble ceramic to a cultural marker

Years following the Partition, a vast gap in the chronology of the subcontinent, of nearly twelve centuries, was the most baffling archaeological problem. It was the proposed ‘Dark Age’ of the subcontinent’s history, which was evidently filled by theories of invasions and later of migrations. It was the time when India was trying hard to find its ancestry. A project involving thorough explorations in Upper Ganga and Sutlej basin was initiated by BB Lal in October 1949. It was under this project that sites like Hastinapur, located in the Mawana Tehsil of Uttar Pradesh’s Meerut district (resonating with the Mahabharata) were taken up for excavation in November 1950 and excavated until March 1952.

Four trenches were taken at the site HST-1, HST-2, HST-3, HST-4.

HST-1 to HST-4 had five occupational periods (I-V) with definite breaks between all of them. In HST-3 and HST-4, remains of Period V were encountered. Period I yielded ochre-coloured pottery whereas Period II yielded PGW along with remains of mud or mud bricks, plasters with reed impressions, copper implements, glass objects, iron slag from uppermost levels, terracotta figurines of animals, bones of horse, pig, cattle.

Lal, while presenting the evidence from Hastinapur following its excavation, made two important revelations: Painted Grey Ware ‘culture’ is associated with Mahabharat; and it dated back to circa 1100-800 BCE.

Lal undertook extensive exploration in the Kuru-Panchal region and found PGW at lower levels. He also found evidence of flood at Hastinapur above Period II, which is PGW period. This flood deposit was linked to the Great Flood from the epic Mahabharat. On excavating Kaushambi, an alluvial deposit was found below the level with PGW. This assessment by Lal ignited debates, which had put this pottery on the pedestal. Since then, many sites were subjected to excavation to test this theory, a topic to be discussed later.

Also read: What came after Harappan Civilisation? This small Haryana village has answers

Where is the culture?

It was the ceramic’s characteristics and distinctiveness that made Allchin and Allchin (1968) call PGW a hallmark of a culture. The highly developed pyro-technology to make this pottery, along with the presence of iron and glass, were argued to lay the foundation of prosperity and an evolved socio-cultural life, unleashing the second wave of urbanisation in Ganga plain, which has a large concentration of sites.

This brings me to an age-old question—can a pottery type define a culture? Is it enough to put the entire responsibility on just a grey potsherd? Agreed that the technique and skills that have gone into making this pottery is unique, something that seems to have been forgotten over a period of time. Is it enough? How much do we know about the layout of structure; the subsistence pattern; trade links; beliefs and social adaptation?

We know that PGW using communities is rural in nature. Mud and mud-brick houses, embankments and wattle-and-daub structures are some of the evidence found at many sites. Community hearths, storage bins, raised platforms are found at sites like Atranjikhera, Bhagwanpura, and Jakhera. A round house at Jakhera has 23 post-holes around it that were exposed during excavation. The work of Makhan Lal in Kanpur district (1984) has also revealed that there were 40 sites of less than 2 ha whereas two sites were 2-2.99 ha and three were 3-3.99 ha. Jim Shaffer and Suraj Bhan’s work in Haryana (Bhan, S and Shaffer, JG. 1978. New Discoveries in Northern Haryana. Man and Environment, Vol. II, 66–6) and study by Erdosy (1985) around the ancient site of Kaushambi are also important. Mughal’s study of Bahawalpur state in Cholistan in Pakistan revealed 14 PGW sites. Satwali is so far the largest site measuring about 13.7 ha. These studies deduced there existed a three-tier settlement with large sized settlements surrounded by smaller settlements measuring 1 to 4 ha. But critical evaluation of the situation along with architectural features like fortifications are missing, and could help strengthen such hypotheses.

With over 1,000 sites mapped and many like Ahichchhatra (IAR 1963-64), Alamgirpur (IAR 1958-59), Atranjikhera (Gaur 1983), Noh (IAR 1998-99), Rupar (IAR 1954-55), Bhagwanpura (Joshi 1993), Chak 86 (Trivedi 2009), etc excavated, we barely know enough to understand the ‘culture’ of PGW using folks. What is fascinating is that the sites are expanded up to Bahawalpur in Pakistan on the dried banks of Ghaggar-Hakra in the west, to Kaushambi in the east, and from Jammu in the north to Kayatha in the south, yet we know nothing about regional cultural traits and variations, micro-adaptive techniques, alliances, or even basic pattern of settlement that could help us weave the story of PGW.

One might wonder if PGW was an innovation of the same potters who innovated Black Slip Ware or Northern Black Polish Ware. The shapes and style of these variants are similar to one another. An aspect that is often overlooked by scholars is plain Grey Ware and its relationship with PGW.

The lack of enough dates from sites and study of material apart from PGW has raised many questions. At Hastinapur, Lal dated PGW to c.1100 BCE, which was supported by few scientifically dated samples. But recent dating from Kampil and Gosna to the third millennium BCE—contemporary to Harappan civilization calls for fresh investigation and detailed discussion in academia. Such efforts could help us with the question of its origin and diffusion.

Until then we have to agree that in the limited area of excavation of PGW cultural horizon, details on many facets of the culture in proper contextual framework have hardly been retrieved. So, the attempts at reconstruction are ‘tentative and more in the nature of overview’ (Tripathi 2012).

Disha Ahluwalia is an archaeologist and junior research fellow at the Indian Council Of Historical Research. She tweets @ahluwaliadisha. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)