As the United States draws closer to India, Pakistan has come to regard China as a life-support machine.

Unlike many in India, I derive no pleasure from the squalid little news clip that shows workers from China beating Pakistani cops and civilians at a Chinese work-camp outside the Punjabi town of Khanewal. Pakistan’s news media described the policemen as having been “thrashed”, a word reflecting the humiliation and feelings of emasculation that have swept through that country in the aftermath of the event.

This violent act of criminal assertiveness on foreign soil lays bare the contempt that the Chinese have for the Pakistanis. The Chinese workers wanted to leave their camp to let off steam at a local brothel. The police who were there to ensure the workers’ security tried to stop them from leaving unescorted, hence the brawl.

The cops’ submissiveness in the face of this assault shows the extent to which Pakistan has become a slavish sidekick of neo-imperial China. The image of a Chinese worker standing atop the bonnet of a police car captures the swagger of a dominant power, and the servility of its vassal.

How did Pakistan plummet so low? Pakistan separated from India in 1947, and, after Jinnah’s death, very quickly abandoned his soothing but hare-brained idea of being an Islamicate (to use a reputed historian’s coinage) version of India—in other words, a Muslim-majority secular, democratic republic.

In truth, Jinnah’s conception of Pakistan was always that of a welfare state for north India’s Muslim elite masquerading as Indo-Muslim nationalism. From the earliest years of its existence, Pakistan has searched hungrily—often desperately—for a raison d’etre. It was no longer India—but what was it instead? Its Independence Day, August 14, doesn’t—like India’s—unequivocally mark a final liberation from the British. It is also the day it parted ways with India, and with the Hindu.

So, Pakistan has had to be, by definition, the un-India, and it proceeded to be the un-India with an almost lip-smacking relish. Its genocide in East Pakistan was its pursuit of un-Indianness in its most hideous form, comprising the physical elimination of those of its citizens who were a reminder of Pakistan’s Indian past, Bengali citizens for whom being Pakistani didn’t mean the abandonment of a Sanskrit-based language and of a culture—song, dress, syncretism and literature—that was deeply rooted in a pre-Pakistani past.

In all of this, Pakistan erased much of its own history. The erasures were replaced by propaganda, and by selective memory. Pakistan embraced the Islamic-era history of India as its own exclusive narrative, and in a magical twist in this narrative, the Mughals were deemed, in spirit, to be Pakistani. (In an unlovely imitation of this process, India’s Hindutva chauvinists today also regard the Mughals as Pakistani.)

But a severing from their own truthful history produces a moral and spiritual rudderlessness in a people. Every people wishes to be the product of a past, and to belong to a culture rooted in that past; and so, Pakistan/un-India came to give itself Persian and Arab and Turkic dimensions as a substitute for the rejected Indic one, and Pakistanis became Persian and Arab and Turkic postulants, or wannabes.

I can think of no other country in the world where the linguistic majority regards its own language as a bumpkins’ tongue, inferior to the national language imposed upon it a mere 70 years ago. Punjabi, in Pakistan, has been reduced to the level of an informal patois, spoken off-duty and among friends, rarely in the office or the classroom.

An existentially rudderless country, Pakistan is always in search of meaning and of friends, and of outlets for its civic and political frustrations. These frustrations have led to the growth of Islamist radicalism in Pakistan, and these radicals have been exhorted onward by the forces of Wahhabi internationalism fanning out of Arabia. Islamist radicalism dovetails conveniently with the project of being the un-India, and terrorism in Pakistan now works overtime (and in partnership with the state) to bleed Hindu India by a thousand little cuts.

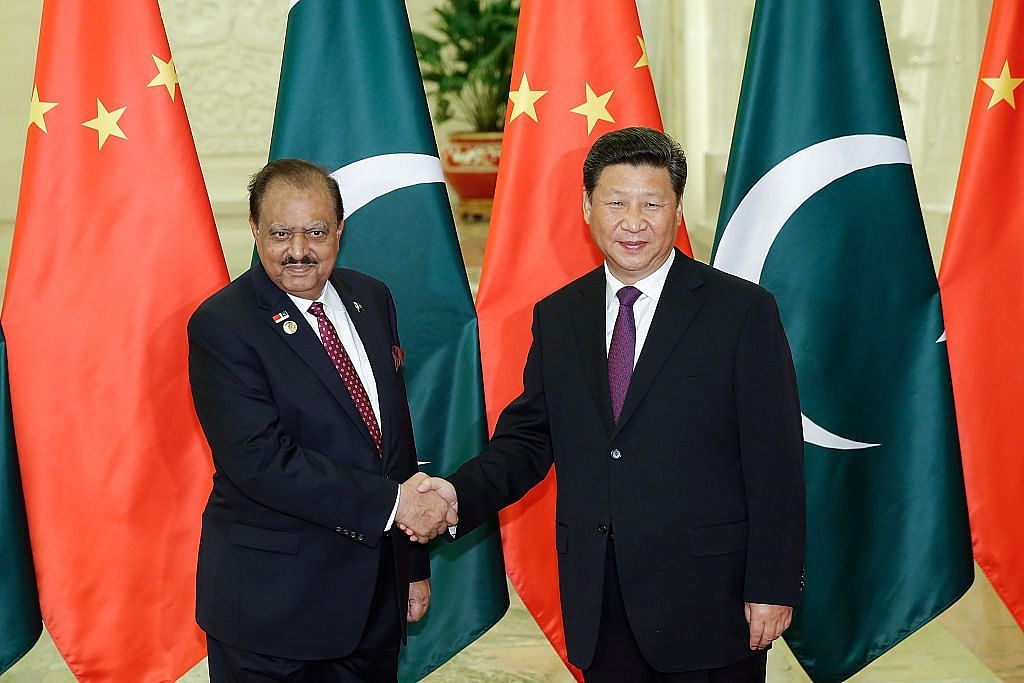

Given the economic and military shortcomings of Pakistan, it cannot take on India by itself. This is where China, with its own implacable hostility to India, comes on Pakistan’s stage. Pakistan has, for decades, been China’s complaisant little crony as a way to stiffen its defences against India. As the United States draws closer to India—while growing ever more distant from terrorist-infested Pakistan—the panicked Pakistanis have come to regard China as a life-support machine. Their fatal error is not just to rely so extensively on China for almost every single one of their needs, but also to fail to anticipate the python-like grip China would have over Pakistan in their bilateral relations. The very army (and ISI) that boasts most loudly of keeping Pakistani sovereignty safe from all aggressors has consigned Pakistan to the most profound vassaldom.

China’s helping hand has not come to Pakistan for free. Pakistan is now tethered to the Chinese, bound to Beijing as a hostage of its own history. Pakistan’s knack for self-delusion has largely prevented it from seeing how thoroughly it is being exploited by China. It has signed away significant amounts of northern land to China (including land that is lawfully Indian), and has practically gifted China a deep-water port in Gwadar that the Chinese are unlikely ever to vacate. And with the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), Pakistan is now in a painful debt trap, Made in China.

The Chinese workers and engineers who rioted in Khanewal are in Pakistan to build a highway from Bahawalpur to Faisalabad. What would Jinnah think, one wonders, of the fact that the country for which he sundered a millennial civilisation cannot even put together its own highways?

There is a long history of Chinese workers going abroad to build infrastructure. Think of the railroad in the American West, and the role of the Chinese “coolie.” He went, then, as a semi-indentured serf, abused and vilified by the natives around him. Today he builds highways, but no one abuses him. In Pakistan, in fact, he is the abuser. He knows that he is among supplicants—and he knows that he owns them. One Belt, One Road…One Thrashing.

Tunku Varadarajan is the Virginia Hobbs Carpenter Fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution.