At a time when there is so much interest in historical narratives, the lack of respect for the physical traces of the historical past is startling.

The passions being aroused by figures and monuments from India’s Muslim past seem to me to be connected to the peculiar place of history in our public life. I think that South Asians are emotionally invested in “owning” their past to quite an extraordinary degree. They need to reconfigure the past so that it connects to their present situation in a very direct and overly simple way.

I am not sure when this begins. Perhaps it comes from the time when colonial narratives had to be opposed, and Indians from different strands of the nationalist movement needed to disprove the colonial idea that Indians were not competent to govern themselves. One important tactic for these histories was to locate “good” kings in the Indian past, to show how indigenous kings had been wise, tolerant and just.

This has set the tone for a lot of history writing ever since, which is full of moral judgments of past rulers and past phases of history on entirely presentist terms. So if the need of the hour is to show that India was multicultural and many communities co-existed in harmony, appropriate periods and rulers are highlighted that prove this to be the case.

South Asians need to reconfigure the past so that it connects to their present situation in a very direct and overly simple way.

And if the need of the hour is to show that communities clashed, and one community oppressed the other, then appropriate periods and historical examples can be found to prove that point.

History is capacious and complex; no period or person can be characterized through a simple stereotype. Sometimes the very same historical figure can have done things that are “good” or “bad” by our lights. Several commentators have written about this presentist fallacy when the past is judged in terms that cannot sensibly be applied to it. What sense does it make to hand out or withhold Indian “nationalist” credentials to a ruler from the 13th or the 18th century?

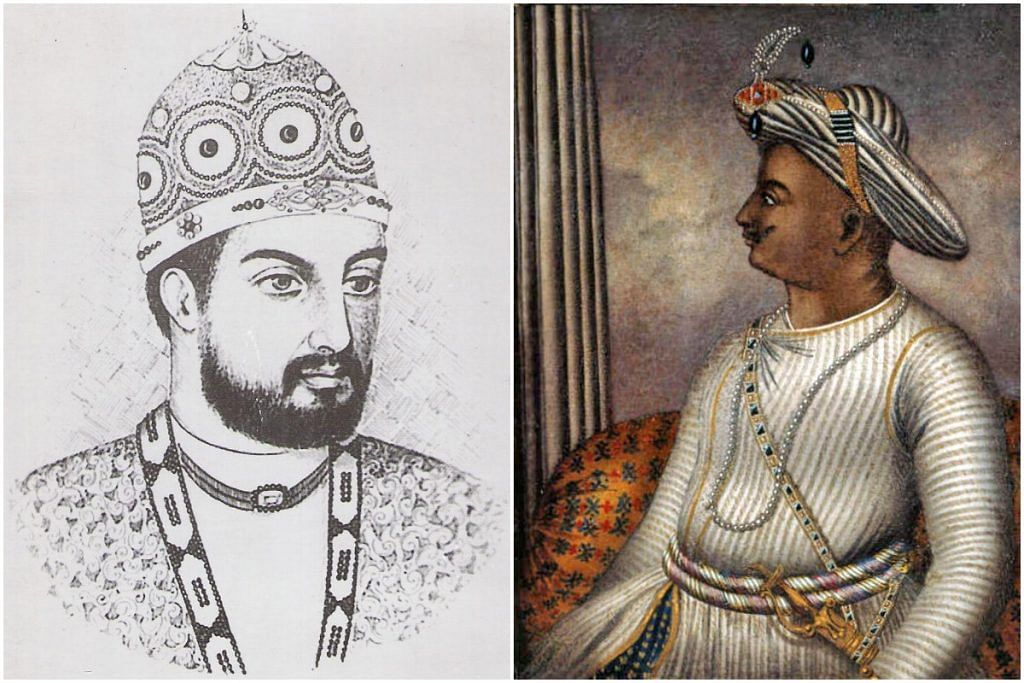

It is worth pointing out the degree of popular involvement and emotional investment in narratives of history in India. People seem to identify emotionally with certain historical figures, adopting them as their Volksgeist, the embodiment of the “spirit of the people.”

And on the flip side, there is an equally strong need for historical villains, for figures who embody the anti-Volksgeist. This is a figure at whose hands a group can claim victimhood, and victimhood is tremendously useful in producing and consolidating a sense of community. This has obvious political utility.

Affronts to the memory of the Volksgeist – or praise of the chosen anti-Volksgeist, the historical villains – arouse tremendous passions in the public sphere. Perhaps a psychoanalytical study will help us understand our collective need for such strongly etched heroes and villains, and why we feel so personally involved in their representation in books, films, and public life. Whatever the reason for this dependence on heroes and villains, I think it is this is at work today in the demonising of India’s Muslim past.

At a time when there is so much interest in historical narratives I am startled by the lack of respect for the physical traces of the historical past. Look at the miserable state of our archives and museums and monuments, and look at the tremendous disinterest of the public in them.

When an archive stores its documents so carelessly that the store rooms get flooded and hundreds of years worth of documents get turned to pulp, is there any public protest? When monuments are demolished or degraded through callous actions of the governments or the public, does anyone mobilize a crowd or start a petition? When museums allow artifacts to degrade or be stolen from the stores, is there an outcry? These are the materials from which a history can be written, but we are not interested in the tangible documents through which a history can be written.

Rather, we are interested in taking offence at what someone has said about our past. This really is an interest in folklore and not history.

Kavita Singh is Professor & Dean, School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University

Also read: Talk Point: Is political polarisation leading to demonising India’s Muslim rulers?