There is a long-held consensus in India that the parties do not sort themselves ideologically, especially regarding economic policymaking. The paper analyses National Election Studies data between 1996 and 2019 by Lokniti-CSDS, and shows that voters cluster around the centre-left position on economic issues. The Indian political elite are, however, ideologically divided and have distinct positions on economic issues. Party experts, journalists and academics acknowledge these differences.

Elite’s conflict on political matters in democracies is often manifested in mass attitudes. Why aren’t these differences among the Indian political elite found in mass public opinion? The masses share a common view on the role of the State because many Indian voters depend on the State for their wellbeing, and those who favour unfettered free markets are too few to constitute a significant catchment for political parties.

For example, the Bhartiya Janata Party members are more likely to favour privatisation, and members of Left parties prefer labour rights. These ideological differences are also evident in our analysis of the manifestos of political parties since 1952 and an expert survey conducted in 2022. We argue that these elite differences in economic policy do not translate into mass politics because all political parties present the State as the solution to economic deprivation. The rise of welfare populism in Indian politics in the past two decades is a result of centralisation within political parties in which the welfare promises are directly linked to the party leaders.

Mass opinions on the Role of the State in the economy

The absence of distinct economic positions among parties has led to the conclusion that party politics in India is non-ideological.

The one exception often mentioned is the Left Front, whose position on the State’s economic policies differs from the more centrist or centre-right policies adopted by the Congress and the BJP. The rise of the BJP in the past decade compelled a spate of revisionist views on the non-ideological nature of Indian politics. The BJP is considered more inclined towards private businesses and greater infrastructure spending and projects a slightly different worldview vis-à-vis India’s welfare state.

For example, in a meeting with the business community in Japan in 2014, Prime Minister Narendra Modi unabashedly proclaimed, ‘Being a Gujarati, money is in my blood … commerce is in my blood.’

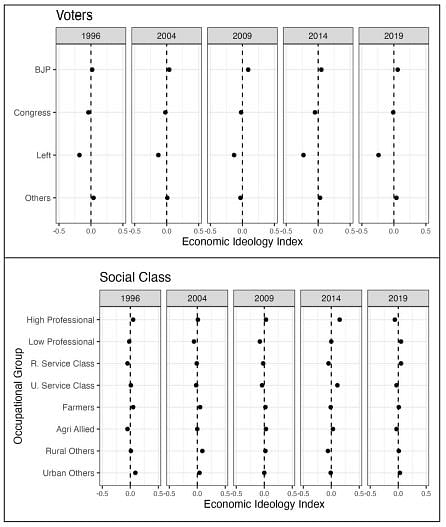

We analyse survey data from NES between 1996 and 2019 conducted by the Lokniti team– CSDS to understand ideological sorting among Indian voters and party members on economic policies. We selected nearly identical questions from the NES surveys that capture citizens’ perceptions of the role of the State in an economy—for example, whether respondents supported limiting land ownership, privatising state-owned companies and reducing the number of government employees, among others. The data presented in Figure 1 shows a clustering of voters around centre-left positions on economic issues, that is, no ideological divide. The opinions of respondents belonging to different social classes (combining respondents’ location (rural or urban) and their occupation) on economic ideology questions were also not statistically very different.

Source: NES 1996–2019, Lokniti-CSDS

Also read: Why do Indian Muslims lack an intellectual class? For them, it’s politics first

Elite views on the role of the State in the economy

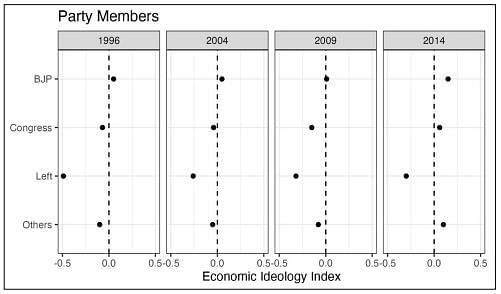

While Indian citizens share common views of the State’s role in the economy, we find discernible differences among the party members in the NES data on these issues.

Source: NES 1996–2014, Lokniti-CSDS.

We find that the BJP members are more to the economic-right position than the Congress members, and the Communist party members are on the economic left. This pattern is replicated across election years for which information on the respondent’s party membership data was gathered. Experts—journalists and academics—believe that Indian political parties have distinct ideological positions in a survey of experts conducted in 2022 by the Centre for Policy Research (CPR).

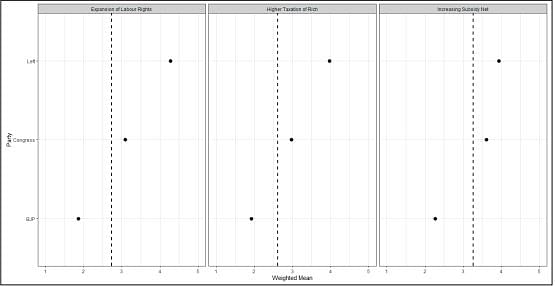

The data presented in Figure 2 and 3 provide unambiguous support that political parties in India differ on economic issues among party members and intellectual elites.

Source: Political Expert Survey, CPR, 2022.

The BJP, in expert perceptions, is less likely to support higher taxation for the rich, the Left parties most likely and the Congress party has a much more centrist position. Similarly, while the difference between the Left parties and the Congress is very little related to increasing subsidy net, the expert’s perception of the BJP places the party below its ideological counterparts as less likely to support subsidies.

Why don’t elite views translate into mass attitudes?

Myron Weiner introduced the concepts of elite and mass culture. Both these cultures, Weiner argued, were permeated by a modernising ethos and traditional cultural values. Mass political culture, for Weiner, represented society’s attitudes towards governance at the local level, circumscribed largely by ethnic concerns. Elite political culture, on the other hand, is located within the national (and state) capital(s), plugged into globally dominant paradigms of development and generating its discourse mainly in the English language, removed from the vernacular idioms.

Ashutosh Varshney builds on these ideas and suggests that elite politics is typically expressed in debates and struggles within the institutionalised setting of parliament, political parties, bureaucracy and national media, whereas mass politics takes place on streets through large-scale mobilisation in the language and issues that voters associate with.

When do elite and mass politics converge on a particular issue? And when does a particular idea or set of ideas become the ideological basis for a political party or party system in India? Pradeep Chhibber and Rahul Verma (2018) indicate that there must be a coherent intellectual tradition that includes oppositional ideas; the conflict between those ideas must be fairly stable with enough number of voters on both sides for an ideological competition to become viable, and the elite must transmit opposing ideological viewpoints.

What ideas have had a stable basis of party competition in India thus far? Chhibber and Verma argue that Indian party politics is deeply ideological, and divisions on the State’s appropriate role have influenced the changes in the Indian party system since Independence.

The transition from the Congress-dominant system to a multi-party competition to a party system centred around the BJP is clearly correlated with the ideological positions adopted by the main political parties. Using NES data, Chhibber and Verma (2018) demonstrate that the BJP succeeded because it consolidated those on the ‘right’, that is, citizens who do not want the State intervening in social norms, recognising minorities, and who equate democracy with majoritarian values.

Although social policy seems to have a large impact on Indian politics, why doesn’t the classic left–right axis on economic policies have the same influence? We argue that there is indeed a coherent intellectual tradition that underpins parties of the right and the left on economic policy, and the opposition between these ideas has been present since Independence. The Indian political elite disagrees on some ideas on the role of the State, such as on how extensive a role should be given to the private sector in the Indian economy and the direct role of the State in manufacturing and services; parties do not disagree on whether the State should make direct provisions for the economically vulnerable. All parties agree that the welfare of the poor is the responsibility of the State.

Economic ideology in India: a historical consensus?

State-led industrialisation was necessary for several reasons, particularly for the Indian economy. First, the industry needed large amounts of capital to establish the industrial base required for sustained and diversified growth. These resources could be mobilised only by the State, especially given India’s low private saving rate. Second, public investment could more easily create an industrial structure without relying on higher corporate profitability levels, which would have increased income disparity.

Third, reliance on public rather than private enterprise would foster growth in the metal, mineral, machinebuilding and chemical industries. In this way, economic power would not be rooted in industrial houses. Support for this expansive role of the State came from across the political spectrum.

Traditionally, the right has often been equated in many countries with market capitalism. Still, the dominant faction of the right-wing in India showed innate suspicion of both unbridled market economics and socialism. There were, in short, just too many contradictory strands in the thinking on economic policy in the Hindu nationalist camp.

Susanne and Llyod Rudolph in their seminal contribution to the study of the political economy of the Indian State argue that political parties in India ‘do not derive their electoral support or policy agenda from distinct class constituencies or from organised representatives of workers and capital’. They suggest, somewhat prophetically, ‘Class politics in India is likely to remain as marginal in the future as it has been in the past.’ They also suggest that conflict between capital and labour in India is less likely to become an axis of mobilisation because of a third actor’s centrality—the State. India’s political economy further constrained the development of a cleavage on economic left–right. A majority of Indians remain in rural areas, a plurality still lives off agriculture and the working class is found in the industrial sector’s unorganised part.

In the organised sector, where one would expect to see a political articulation of the capital–labour divide, few independent trade unions exist. The major trade unions in India are all tied to political parties. The standard capital–labour conflict is also muted because most employment in the organised sector, especially throughout the 1970s and 1980s, was in the public sector. So, labour’s conflict was less with capitalists than with the State.

Similarly, the divide between urban India and Bharat (a euphemism for rural India) has been crucial during specific periods in independent India’s history. Still, it did not represent a stable political division. The 1960s and 1970s were marked by a tremendous increase in legislators with rural origins and agriculturalist backgrounds, both in the Parliament and in many state assemblies.

Even with increasing urbanisation, virtually no party has yet made efforts to rely on projecting just urban interests.

Similarly, while the proportion of the population that identifies itself as the middle class in the survey has also increased multi-fold. However, given the overwhelming demographic weight of voters in low socio-economic segments, no political party sees any advantage in being associated with merely pro-middle class or pro-urban position—the equivalent of a political suicide. Even the so-called right-wing government led by the BJP has made removing poverty a central plank of its political agenda.

Also read: Vote in the Lok Sabha elections, but know it’s just a symbolic gesture. Voice matters more

Welfare populism: a new consensus?

It is not a coincidence that Narendra Modi’s rise on the national centre stage coincided with the structural shift with a fall in the ranks of the poor and increase in the aspirational neo-middle class ranks, creating an audience for the new narrative of empowerment. By promising a reformed state that would unleash new entrepreneurial energies without the past cronyism, Modi sought to win over a broad cross-section of society.

Although it is true that the data points in the NES surveys over time are not strictly comparable as the questions asked in different election years are not the same, we do notice that there are now more voters who are rightward leaning on economic issues than the past, and this small section (and growing) of the economic right has mostly supported the BJP in the post-1991 era.

In some ways, Narendra Modi, as the chief architect of the BJP’s campaign, could be credited with coalescing economic right towards the BJP. While Modi’s candidature made no difference to the vote choice of social and religious conservatives, who were likely to vote for the BJP, Modi drew the economically rightward voters to the BJP in 2014, according to an NES survey. The politics since the rise of the BJP represents a distinctive approach to redistribution and inclusion, which Anand et al. describe as the ‘New Welfarism’.

The increasing centralisation within Congress under Indira Gandhi accelerated welfare populism. And this model of combining leadership appeal with promising distribution of state resources during election campaigns got adopted by other parties too. Despite this, the consensus among scholars that differences between political parties are ‘far from a real substantial choice’ is not borne out by a systematic examination of party documents (including manifestos). Even though parties share common views on welfare, they emphasise other economic policy elements.

Compared to other parties, the Congress and the BJP allocated a greater space to free market policies. Labour rights are a constant priority for the Left in every manifesto, and it gets a token mention in the BJP and Congress manifestos. Left parties also talk about land consistently, usually with respect to tenancy reforms. On the other hand, economic goals are prioritised by the BJP significantly. This can include the reform of the financial sector, banking sector, foreign trade, taxation and fiscal deficit, among others.

The Congress also talks about economic goals but not as much as the former, while Left parties barely mention this category (though the 2019 election manifesto was a notable exception). Finally, agriculture and farmers get high importance in all manifestos, with almost one-fifth of space within the economy domain dedicated to this category, but parties highlight very different approaches to tackle this issue. Interestingly, the BJP has dedicated almost half of its space to this category in 2019, which is four times more than that of 2014, suggesting a relation between issue emphasis in manifestos and policy pursuits.

Conclusion

In contrast to the long-held scholarly consensus that there is no divide in economic ideology in India, the analysis presented in this paper clearly demonstrates that although this assertion is true for mass attitudes, the same cannot be said for the elite segments of the Indian population. The demographic features of the Indian population (a large majority is poor, lives in rural areas and off agriculture, and depends on the state for their well-being, among others) will continue to constrain the salience of the economic left-right axis.

This article is an excerpt from original article ‘Economic Ideology in Indian Politics: Why Do Elite and Mass Politics Differ?’ authored by Rahul Verma, a fellow at the Centre for Policy Research (CPR) and Pradeep K Chhibber, an expert on Indian politics. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)

The biggest curse on our country is socialism. Founding fathers of the constitution sowed the seeds of socialism and now it has become a giant tree which can’t be pruned or uprooted.