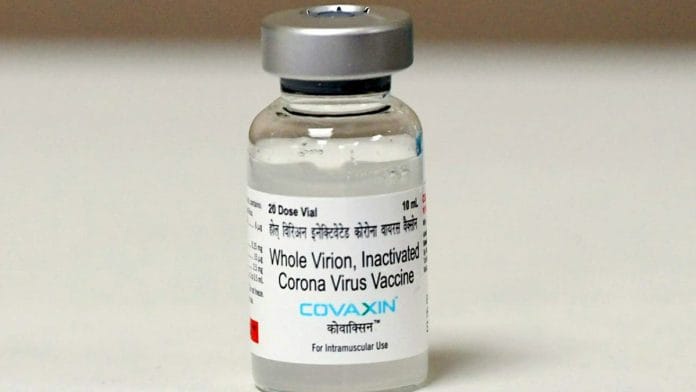

Over the last 10 months, more than 11.83 crore doses of Covaxin, Bharat Biotech’s Covid-19 vaccine, have been administered in India. Yet, eight correspondences seeking clarifications/data from the World Health Organisation, a meeting between health minister Mansukh Mandaviya and WHO Director-General Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesu, and much national outrage over the “preferential treatment to China” later, a place in WHO’s emergency use list continues to elude India’s indigenous vaccine.

The narrative about WHO’s “discrimination” has now got a life of its own with anchors gesticulating and experts outraging across television channels. But, if for a second, that noise is muted, then there are some genuine questions that the Narendra Modi government may have to answer about the data that it had when the vaccine started being pushed into people’s arms on 16 January. The vaccine was given emergency use authorisation without phase III efficacy data on the presumption that, as a whole virus-based vaccine, it would work better against variants of the SARS-CoV-2.

There is much to mull about where we stand on the use of indigenous vaccines more than a year into the pandemic. While the WHO is still evaluating Bharat Biotech’s Covaxin, the debate has turned many believers into skeptics. The fact that it’s taken so long for the vaccine, which is touted as ‘one of the best’, to get approval casts doubt on not only its producers and the product, but also the regulatory process in India. And that is why Covaxin’s battle to get on the emergency use list (EUL) is ThePrint’s newsmaker this week.

Bharat Biotech applied for EUL way back in May. There were some pending documents at that point but the process was underway. Subsequently, between 16 August and 14 October, eight communications from WHO arrived seeking additional information and were duly replied, giving details as sought. This included all clinical information, non-clinical information, chemistry, manufacturing information, and information about controls. The matter was also discussed at great length on 19 October during the meeting between health minister Mansukh Mandaviya and WHO DG Dr Tedros. Yet, the vaccine failed to get the necessary nod on the 26 October meeting of the Technical Advisory Group (TAG) of the WHO. It will now be up for evaluation on 3 November. Comparisons have since erupted over the easy passage of the vaccine manufactured by Chinese drugmaker Sinopharm into the WHO EUL way back in May and also questions about WHO’s impartiality.

Update: The @WHO independent TAG met today & asked for addnl clarifications from the manufacturer @BharatBiotech to conduct a final EUL risk-benefit assessment for global use of #Covaxin. It will reconvene for the final assessment on Wednesday, 3 November if data received soon

— Soumya Swaminathan (@doctorsoumya) October 26, 2021

The Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), which partnered with Bharat Biotech in the making of the vaccine, has maintained a stiff upper lip through this, but officials have been saying off-the-record that the holdup is “diplomatic, not scientific”.

Also Read: DCGI’s Covaxin ‘approval’ is political jumla. It reinforces idea of Modi’s Atmanirbhar Bharat

Indian regulatory process for Covaxin

To date, the phase III data (that claims that the vaccine is 77.8 per cent effective against symptomatic Covid-19) is yet to be peer-reviewed — an important step in validating scientific data. The pre-print on the medRxiv site has comments that raise various questions including the statistical significance of the efficacy claims and the way the trials were done in various parts of India, allegedly without regard for the rules for clinical trials such as informed consent.

India’s own record of data collection is dismal and its commitment to transparency is questionable. A billion vaccines later, the Modi government is yet to give out the numbers of breakthrough infections in the country, or the number of people who, in the last 21 months, have been down with Covid-19 more than once. There are many other data points on which the Modi government has remained vague, some say, deliberately.

While peer review is not an essential criterion for WHO, the fact that vaccine data has been repeatedly found wanting on the international stage may call for more scrutiny of domestic processes than the one that Covaxin has failed.

The statement from the WHO last week reads: “The timeframe for the WHO Emergency Use Listing (EUL) procedure is dependent on how quickly the company producing the vaccine is able to provide the data required for WHO to evaluate the vaccine’s quality, safety, efficacy and its suitability for low- and middle-income countries. We are aware that many people are waiting for WHO’s recommendation for Covaxin, but we cannot cut corners – before recommending a product for emergency use, we must evaluate it thoroughly to make sure it is safe and effective.” Crores of Indians were given Covaxin. There was no option of choosing the vaccine. For them, the phrase “cutting corners” ten months on, has an ominous ring. It raises some critical questions that neither the Modi government nor Bharat Biotech seems to be in the mood to answer.

Also Read: Why Bharat Biotech’s Covaxin is the object of national pride & scientific scepticism

Not much “benefit” for WHO

While the fulcrum of the outrage in India has been the inability of Indians who took the Covaxin shot to travel abroad, for WHO this is what the EUL entails. “The WHO Emergency Use Listing (EUL) is a procedure for assessing unlicensed vaccines, therapeutics and in vitro diagnostics during public health emergencies with the ultimate goal of expediting the availability of these products to people who need them,” reads the EUL information on the WHO website.

Herein lies the catch. Bharat Biotech, for all the chest-thumping nationalism that its vaccine has generated in India, has consistently underperformed on its domestic commitments. In August, when the Modi government gave out projections for vaccine availability for the remaining five months of the year, it had projected availability of 55 crore vaccine doses at a rate of 11 crore per month. To date, India has administered a total of 11,87,73,704 doses of Covaxin. The mainstay of India’s vaccination programme has been foreign-born India manufactured Covishield, and not the indigenous version.

This means that even if the WHO were to give Covaxin the nod for EUL, the company may not have that many vaccines to spare and vaccinate the world. As TAG does a risk-benefit assessment to determine if Covaxin can be used outside clinical trials, this is a fact that will inevitably weigh on their minds. It may not influence the ultimate decision but it will impact the pace at which it is taken.

Views are personal.

(Edited by Srinjoy Dey)