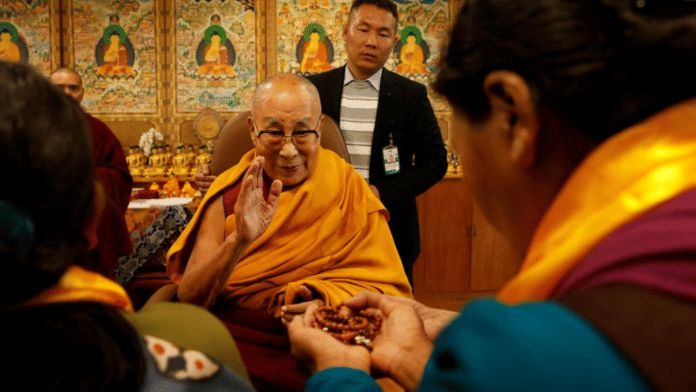

Eighty-eight years after the 14th Dalai Lama was identified as the next spiritual and political head of Tibetan Buddhists, a succession battle has reignited a decades–old spiritual, political, and global flashpoint over freedom, faith, and frontier disputes.

Ahead of his 90th birthday this week, the Dalai Lama made a much-awaited announcement: the institution of the Dalai Lama will continue after his death, and his 2015 Trust, Gaden Phodrang Trust, shall have the sole authority to identify his successor. China is fuming over this declaration. It has swiftly rejected the claim, insisting the successor must be “approved by the central government”.

In the larger gamut of tumultuous India-China relations, the Dalai Lama has been a constant contention for China. The fresh announcement has riled up China that has long accused India of giving the Dalai Lama refuge. And that is why it is ThePrint’s Newsmaker of the Week.

The Union Minister for Minority Affairs, Kiren Rijiju, on Thursday rejected China’s claims, asserting that only the Dalai Lama has the authority to determine his successor.

China, in response, urged India to handle Tibet-related matters with caution, objecting to Rijiju’s remarks.

India’s Ministry of External Affairs appeared to distance itself from Rijiju’s remarks, emphasising that the government “doesn’t take any position or speak on matters concerning beliefs and practices of faith and religion”.

China asserts that its control over Tibet dates back to the 13th century, during the Yuan dynasty, though this claim is disputed. Chinese authority was established in the region in the 1950s, and since 1959, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has governed Tibet directly. Today, Tibet is officially recognised—both domestically and internationally—as part of the PRC, and is designated as the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR).

Beijing, therefore, claims the right to approve all high-level reincarnations within Tibetan Buddhism, including that of the Dalai Lama. In making the claim, China cites a tradition dating back to the Qing dynasty in 1793, when a golden urn ritual was introduced to select high-ranking lamas.

The Dalai Lama has long challenged this claim. In 1969, he asserted that only the Tibetan people should decide the institution’s future. After stepping down from political duties in 2011, he reaffirmed that the selection of his successor rests entirely with the Tibetan religious community.

A legacy forged in exile

China and Tibet have a long history of conflict. Tibet is seen as strategically vital to China, and it also acted as a buffer zone between British India and China. In the early 20th century, when Britain asserted influence in the region, China feared that an ungoverned Tibet could grow closer to India, with which Tibet shares deep cultural and religious ties. India has historically been a spiritual and cultural beacon for Tibetans, being the birthplace of Buddhism and a sanctuary for the Dalai Lamas.

Born in 1935 in what is now China’s Qinghai province, the Dalai Lama was recognised at the age of two as the reincarnation of the 13th Dalai Lama. In March 1959, when a national uprising against Chinese rule was violently suppressed, the Dalai Lama fled Lhasa and crossed into India through Khenzimane in present-day Arunachal Pradesh. By 1960, the Indian government, under Jawaharlal Nehru, had settled him in McLeodganj, Dharamshala, where he established the Tibetan government-in-exile.

Over the following seven decades, he became a symbol of hope and resilience for generations of Tibetans living in exile, serving first as their political leader and later as the spiritual head of Tibetan Buddhism.

China views control over the next Dalai Lama as critical to cementing its authority over Tibet. While he has long advocated a “middle way” seeking autonomy, not independence, Beijing still labels him a “separatist” and a “wolf in monk’s clothes”.

Following the Dalai Lama’s death, there is traditionally a 49-day period during which his consciousness is believed to be in transition, searching for a new form, often human. After this period, the search for his reincarnation begins, a process that can take several years. This responsibility lies with a close circle of monks, as part of his trust, who have served the Dalai Lama. Once they identify a potential reincarnation, they consult with senior monks to gather their opinions.

The present Dalai Lama has consistently said his reincarnation should be located in a free country, and any process under Beijing’s control should be considered invalid.

Many Tibetans fear that once the Dalai Lama dies, Beijing will attempt to install a state-approved successor in order to legitimise its control over Tibetan Buddhism and suppress Tibetan identity.

Their fears are not unfounded. In 1995, after the current Dalai Lama identified a six-year-old boy as the 11th Panchen Lama—the second-highest spiritual figure in Tibetan Buddhism—the child was taken into custody by Chinese authorities and has not been seen since. This year, the Chinese-appointed Panchen Lama publicly expressed allegiance to the Chinese Communist Party during a meeting with President Xi Jinping.

In his book, Voice for the Voiceless, the Dalai Lama warned Tibetans to reject any successor “chosen for political ends”, especially by the Chinese government, and said his next incarnation would likely be born outside China.

Also read: For India and China, 2025 is a year of managed contestations, not breakthrough in ties

Global stakes

The US, too, in order to counter China, has long supported Tibet’s right to self-determination.

In June 2024, the US Congress passed the Resolve Tibet Act, calling for direct dialogue with Tibetan leaders, recognising Tibetans’ right to self-determination, and countering Chinese disinformation about Tibet. The same month, a US congressional delegation met the Dalai Lama in Dharamshala and pledged to defend Tibetan religious freedom.

Beijing, however, dismissed the law, reiterating that Tibet is an “inseparable part of China” and warning against foreign interference.

The Dalai Lama’s announcement now sets the stage for a critical confrontation over Tibetan religious identity and political autonomy. The battle over his reincarnation is no longer just a matter of theology, it is now a geopolitical contest with global implications. Although China officially upholds atheism, particularly within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which typically bars members from practicing religion, it remains overtly involved in regulating religious practices across the country.

Views are personal.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)